The conventional wisdom holds that politicians can’t be trusted to keep their promises, yet decades of research across numerous advanced democracies shows the opposite. In truth, political parties reliably carry out the bulk of their campaign pledges, especially in majoritarian systems like Westminster.

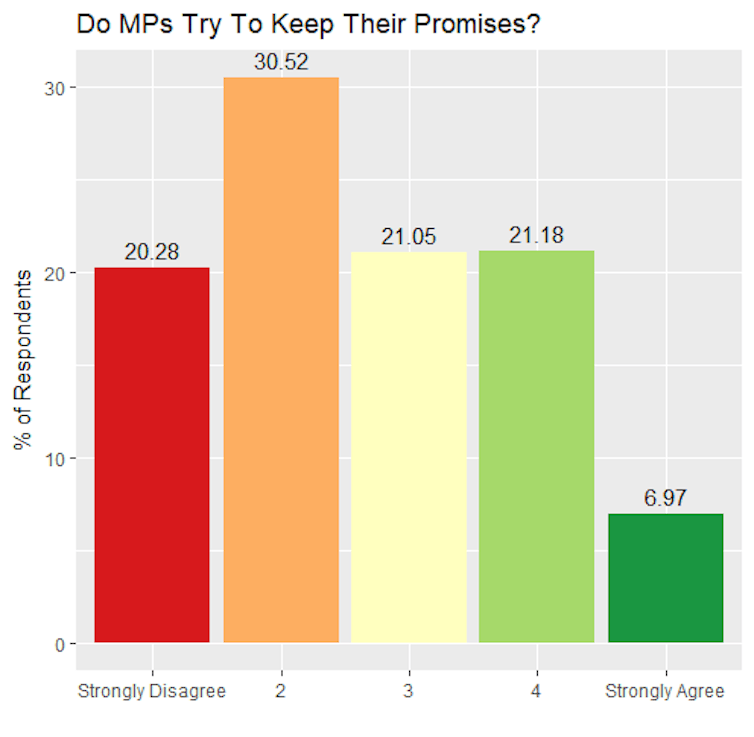

At a time of such political cynicism, the average voter could be forgiven for doubting this claim. The idea that politicians are insincere about their campaign pledges is reflected in public beliefs about election pledge fulfilment. When Chris Carman and I ran a survey earlier in 2019, the findings of which will be published in an upcoming John Smith Centre report, we asked respondents whether they agreed that “the people we elect as MPs try to keep the promises they made during the election campaign”.

Of the 1,435 respondents who offered an opinion, fewer than one in three agreed, while more than half disagreed. Citizens seem to have little faith that the policies they endorse at the ballot box will ever come to fruition. But the truth is actually rather different.

Promises made, promises kept

The finding that political parties carry out their pledges has stood up to repeated, cross-national study. A rapidly growing field of scholarship is dedicated to investigating the connection between manifesto promises and subsequent government policy, known among experts as the “programme-to-policy linkage”. Researchers search party manifestos for measurable policy pledges and check government actions, legislation and news media sources for evidence of their progress.

The most comprehensive study of the programme-to-policy linkage was published in 2017. It brought together 20,000 specific campaign promises from 57 elections in 12 countries. The strongest linkage is found in the United Kingdom, with over 85% of promises by governing parties at least partly enacted in the years studied.

There are also patterns in campaign pledge fulfilment, with a substantial difference observed between consensus and majoritarian democracies.

We also know that promises are more often fulfilled when a party does not have to share power with others, such as in a coalition government. In political systems like Austria and Italy, where coalition governments are the norm, fewer election promises become government policy. The politics of compromise is built into these democracies but it does mean that governing parties typically fulfil only half of their manifesto pledges.

Pledge fulfilment is also affected by factors like economic growth, coalition negotiations and the previous governing experience of parties.

The pledge paradox

The take home message from this area of study is that politicians do seem to try to keep their promises. The central mechanism by which vote choices are supposed to translate into policy works more smoothly than voters assume. This disconnect between public beliefs and the academic consensus even has a name, the pledge paradox.

Why are public beliefs out of sync with the evidence? A recent study shows that negativity bias – the tendency for people to react more strongly to negative information – is the reason that voters remember broken pledges better than fulfilled ones. Meanwhile, a new paper of mine, suggests that voters only react to the fulfilment or breakage of promises on issues they care about. Perhaps parties are damned if they do, damned if they don’t.

Hedging about pledging

Both political parties and researchers, however, must confront questions about the importance of pledges enacted by parties. A recently completed study of pledges from the 2017 Conservative manifesto shows that the promises considered more important by voters were less likely to be kept. For example a pledge to make maps of school buildings available to parents was kept, while the commitment to reduce net migration to below 100,000 was again broken. An impressive fulfilment rate of 69% declined to 48% when they were weighted by voter priority.

Separately, the volunteer-run Policy Tracker project also recently completed its analysis of the same manifesto. The group categorised pledges differently from past researchers, including more subjective statements in the analysis. Using this method, it reports that just 29% of the previous government’s pledges were fulfilled, with a further 55% “in progress” by the time the 2019 election was called.

Although these newer approaches add nuance to our understanding of the linkage, it remains the case that governments make a sincere effort to carry out most promises. It is uncommon for British parties to outright break promises – this happens most often when they are forced to compromise with others or get defeated in parliament. Famous recent examples include the Liberal Democrats’ pledge to abolish tuition fees in 2010 before entering a coalition government with a party that opposed the idea. Then, of course, there was the Conservatives’ failure to pass a Brexit deal after the 2017 election.

Although fulfilling election pledges is not the be-all and end-all of democratic processes, it’s fair to say that the research rebukes the conventional wisdom that campaign promises are worthless. On the contrary, political parties take them very seriously.