In 2014, 1.88 million tourists visited the Great Barrier Reef, bringing an estimated A$5.17 billion into Australia’s economy and helping to employ some 64,300 tourism workers.

With those numbers, it’s easy to see how threats to the Reef’s future, such as the recent mass bleaching event, are confronting for the tourism sector. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many tourism operators have chosen to remain quiet about their concerns or downplay the issue, fearful that mentioning the threats would turn tourists away.

The federal environment department evidently felt the same way, judging by its request that all references to Australian World Heritage sites, including the Reef, be removed from a UNESCO report on climate change and World Heritage tourism.

But does this reasoning stack up? Three other famous tourist destinations have also been in the spotlight of the World Heritage Committee, with little indication that this has turned visitors away.

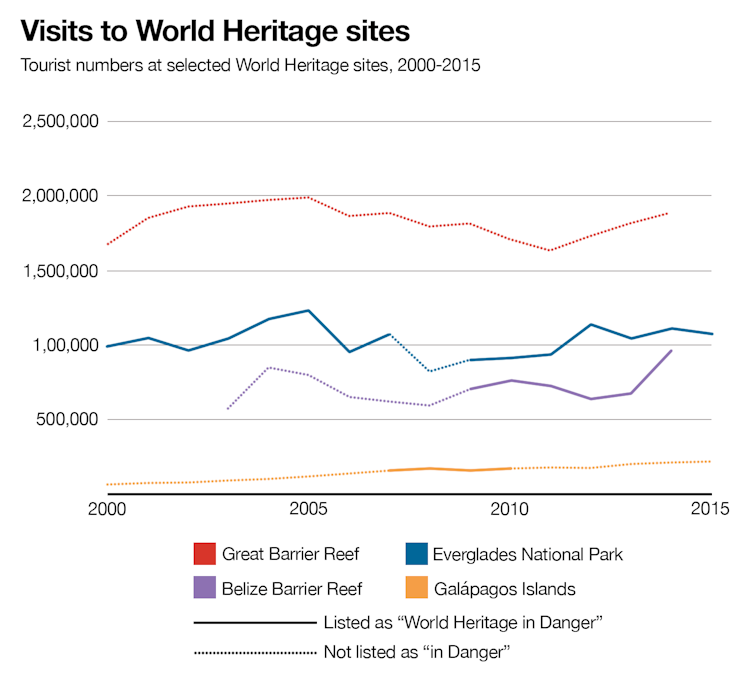

Galápagos was listed as World Heritage In Danger from 2007-10, primarily because of the impacts of tourism, and was taken off again once the World Heritage Committee was satisfied that its concerns had been addressed. The area is now facing other issues, including biosecurity, sustainable development and fishing, but Galápagos tourism continues to grow, as shown in the graph below, with almost 225,000 visits in 2015.

Everglades National Park was listed as World Heritage In Danger in 1993, and remains on the list today (although it was briefly taken off in 2008 before being reinstated in 2010). Annual visitor numbers have fluctuated around the 1 million mark, although official figures count only those who pass through the park’s entrance stations, and many more people enter through the miles of surrounding waters.

Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System

Belize’s reefs have been on the World Heritage In Danger list since 2009, due to a range of issues including invasive species, oil and gas exploitation, and inappropriate visitor accommodation and associated infrastructure. Tourist numbers recently reached a high of 968,131 cruise arrivals in 2014.

What can we learn from these numbers?

The first thing to note is that the Great Barrier Reef has, to date, avoided being listed as World Heritage In Danger, thanks to last year’s successful campaign by the federal and Queensland governments – although there is no guarantee it will not be added in the future.

But what do the statistics above tell us about what happens to tourism numbers when World Heritage sites are officially listed as “In Danger”?

Galápagos suffered a very slight downturn in tourism after it was added to the In Danger list in 2007, but since then tourism has continued to grow, and today numbers are higher than they have ever been.

In Belize, tourism has fluctuated since the site was listed as World Heritage In Danger in 2009, but here too, tourist numbers today are at record highs despite the fact that these reefs remain on the In Danger list.

Finally to the Everglades, which has been placed on the World Heritage In Danger list twice – both times at the request of the US government. This shows that, while sites can be taken off the list if their prospects improve, not all governments think that an In Danger listing is itself a bad thing. Certainly, Everglades tourism numbers do not seem to have suffered since it was placed back on the list in 2010.

Why did the United States lobby to have the Everglades officially described as In Danger, while Australia fought to keep the Great Barrier Reef off the list? As Carol Mitchell, Deputy Director of the South Florida Natural Sciences Center, has explained, the In Danger listing makes it clear to the national and international community that the Everglades still needs attention. Mitchell wrote to me:

It helps to keep some external pressure on both the federal and Florida state governments in their efforts to restore the park … both governments are strongly committed to Everglades restoration; nevertheless … the ability to call upon important, very visible international designations … does help to maintain those commitments.

Tourists already know the Great Barrier Reef is threatened

Despite what the Australian government and many tourism operators would like to believe, the threats to the Great Barrier Reef are already widely known, because they have drawn global media attention.

How this translates into the perceptions of prospective tourists in not yet clear. But the indications from elsewhere around the world is that In Danger listing does not have a significant impact on tourism, and presumably we could say the same about inclusion in documents such as UNESCO’s tourism report.

Many other factors are far more important to tourists, including the economic situation, access, weather events, service quality and, importantly, a site’s relative quality compared to alternative destinations.

Tourism operators are increasingly recognising that the Great Barrier Reef faces myriad threats, and that its outlook is poor. Many people agree with Tony Fontes, a dive operator from the Whitsunday Islands, who previously told me that an In Danger listing “might actually be the catalyst to ensure the GBR is properly protected”.

Recently, other GBR tourism operators have spoken out about the worst crisis ever faced by the GBR, with some 200 businesses and individuals pleading with the government to tackle climate change and the many other threats that together threaten the Reef’s future.

What needs to be done?

Ignoring the indisputable fact that the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem is under unprecedented pressures will help neither tourism nor the environment in the long term. A more effective strategy would be for the relevant agencies and operators alike to create realistic expectations, and responsibly inform tourists of the real situation.

University of Queensland professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg has summed up the situation:

The reef is in dire trouble, but it’s decades away before it’s no longer worth visiting. That’s the truth. But unless we wake up and deal with climate change sincerely and deeply then we really will have a Great Barrier Reef not worth visiting.

Australia has an international obligation to safeguard the Great Barrier Reef for future generations. As a relatively rich country, Australia needs to show global leadership, but this will require more government assistance, leadership from industry and, crucially, widespread public support for action. If reef tourists from around the world know the real situation, they might be able to help too.