The voice is an important tool which we use to communicate and express ourselves. But our voices convey so much more than the words we say. Just a few words can reveal clues about someone’s gender, age, place of birth and mood.

The voice is also extremely flexible in its expressiveness. It’s under constant vocal modulation - one minute whispering in a library then involved in conversation in a noisy pub. There are also vocal changes that happen less deliberately when we speak, such as when we start to pronounce words in the same way as our friends or flatmates. This reflects friendship and mutual approval.

We recently published the first investigation of how the brain controls vocal modulations. Using an imaging technique called functional MRI (fMRI) - which measures brain activity by looking at changes in bloodflow - we looked at brain activity in amateurs while they performed spoken impressions.

We were interested in how they spoke, rather than than what they said, we kept the words constant throughout so we asked the participants to repeatedly recite the first line of a familiar nursery rhyme, for example “Jack and Jill went up the hill”.

Och-aye-the-noo

On different repetitions, we also got them to say the phrase using their normal speaking voice or in a regional/foreign accent of English (for example Yorkshire, French or Scottish) or to do it as an impersonation of a familiar person, such as Jonathan Ross, their mum or the Queen. We then looked at how their brains responded differently when their voices changed, and how this differed between generic accents and specific impersonations.

Although some people express sympathy that I had to listen to 23 amateurs performing impressions, some of our test subjects were actually quite talented and it was a fascinating experience. But it wasn’t important to us how well people could mimic Tony Blair or Prince Charles. All our participants understood what was required, and the task offered a good approximation for the voluntary vocal changes we perform every day.

Importantly, this is something that had never before been investigated using fMRI. To date, most research has been concerned with the control of linguistic output, rather than speaking style or vocal identity.

In our results, we found that regions in the frontal part of the left side of the brain were more strongly activated during both accents and impersonations. These structures, called the insula, and the left inferior frontal gyrus, have long been associated with the planning of speech. When these regions are damaged, for instance by a stroke, speech becomes severely impaired.

When our participants changed the way they spoke to perform an accent or impression, they may have been using these brain regions to form or access modified mental plans for certain speech sounds. We think that the insula might be involved in more general aspects of vocal behaviour during impressions, such as the control of breathing that we need to change the volume and pitch of our voices.

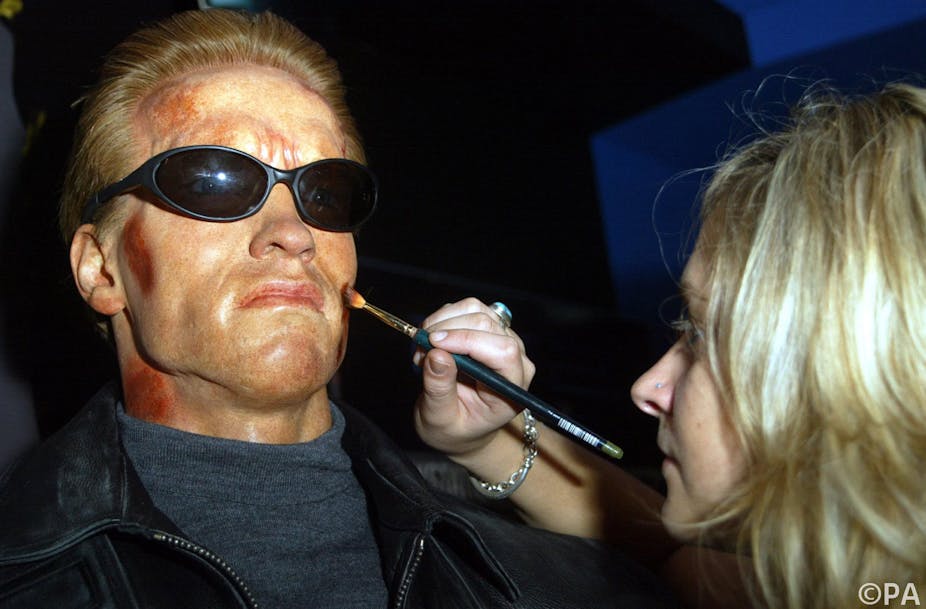

Austrian or Arnie

When we compared the brain activity for accents (for example Austrian) to that during specific impersonations (for example Arnold Schwarzenegger), we found greater activation in several regions of the brain for the impersonations.

This included areas in the temporal lobe of the brain that have previously been associated with listening to voices and perceiving familiar identities.

It’s the first time that these brain areas have been implicated in producing speech and the control of vocal output. In further analyses, we showed that these temporal regions work together with the frontal areas (the insula and inferior frontal gyrus linked with the planning of speech) to produce impersonations.

From this, we think that when we perform a specific impersonation we activate an auditory “image” of the voice of the person we want to imitate. We then use this information together with our modified speech plans to execute the task.

Next step, beatboxers

I’m fascinated by vocal experts. To some extent, we are all expert vocalists through our use of speech, as it’s an extremely complex motor act. However, professional impressionists and beatboxers take vocal control to another level of sophistication. Our next step will hopefully be to investigate how the brains of professional voice artists respond when performing our impressions task in fMRI and we’re very keen to hear from volunteers.

Alongside the very useful linguistic information in speech, the voice communicates who we are, and very often who we want to be. We hope our work helps develop understanding of the neural control of the voice.