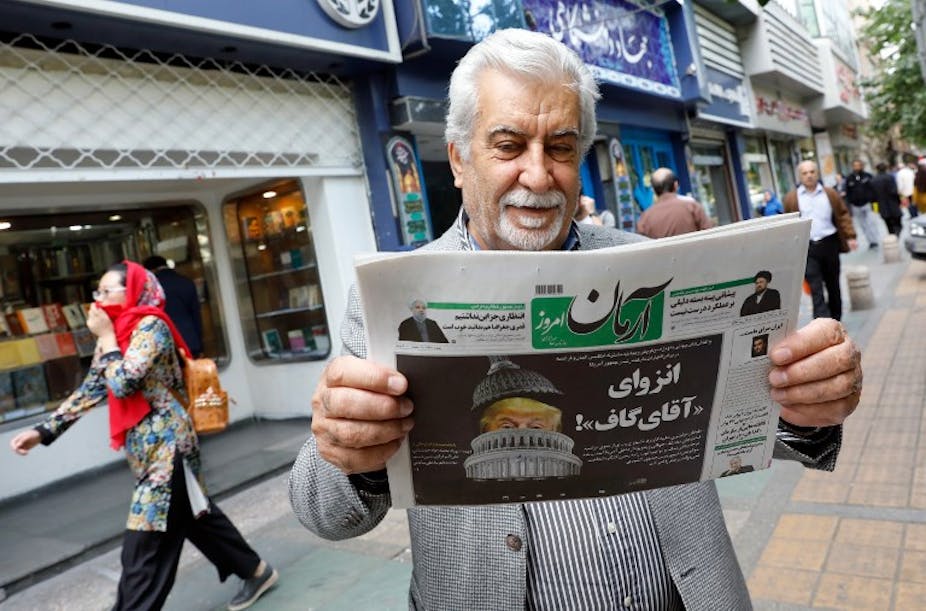

The October 13 decision by US president Donald Trump to “decertify” Iranian compliance to the 2015 nuclear nonproliferation agreement could signal the end of US soft power in Iran.

In his speech, Trump attempted to emphasise Iran’s deep history, which he said the Iranian people “long to reclaim”. Yet in doing so he employed the term “Arabian Gulf” rather than “Persian Gulf”. He also invoked the Iran of the early revolutionary years, when Tehran was at war with the regime of Saddam Hussein (1980-88) and failed to take into account the sociocultural transformation of the last 38 years.

Within Iran, Trump’s discourse was perceived as anachronistic and out of context. The country’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, stated that the attempt to send Iran back 50 years was a demonstration of Trump’s “mental backwardness”. Moreover, the 2015 agreement was widely approved and positively perceived by the country’s citizens.

Trump’s speech and his decision could provoke a return to the anti-Americanism of Iran’s early post-revolutionary years by the country’s hardliners. Many called the speech disrespectful of Iran’s status as one of the regional powers in Southwest Asia.

The war of words

Iran’s government and that of the United States are now accusing one another of not respecting the deal, yet another illustration of the mistrust that has grown since Trump was elected.

Tehran fears that an escalation of the war of words will hinder the economic benefits that Iran had anticipated gaining from the agreement. Even if the United States does not actually pull out from the nonproliferation deal, the harsh criticism of Iran’s regional ambitions and missile-development program bring into question the country’s policies. And with it, the previous US administration’s actions in the region.

In his speech, Trump announced that the US Treasury Department will be authorised to impose additional sanctions on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Known as the Pasdaran in Persian, the IRGC is a military force as well as economic conglomerate established after the 1979 revolution. Trump accuses it of support for “terrorist” organisations, but in retaliation, Tehran could place the US Army on its own list of “terrorist” organisations.

The deterioration of the two countries’ relationship also increases the risk of a military confrontation. Brigadier General Massoud Jazayeri has previously stated that “hundreds of thousands of American forces are present in the region” and that if the US forces move “too far”, especially in the Persian Gulf, the “Islamic Republic will confront them”. This repeated a similar warning last March.

In Trump’s over-simplistic narrative, Iran is a “rogue regime”, a depiction that heightens nationalistic feelings. This is particularly the case given that the United States has longstanding ties to Saudi Arabia, Iran’s main regional competitor.

Trump’s rhetoric is a drastic shift from President Barack Obama’s sensitive diplomacy toward the Iranian people. He took special care to distinguish between Iranians and the regime in power, quoting poets such as Hafez in his annual New Year (Nowrouz) address.

Impact on the Iranian economy

The shift in US policy is potentially a serious blow for the Iranian economy. The IRGC has a powerful economic role and new sanctions could result in a loss of foreign investments. New sanctions could provoke a devaluation of the rial and the return of double-digit inflation because of the rise of uncertainty regarding the future of the US legal framework.

Tehran is counting on European countries to help protect the 2015 deal and has even strongly suggested that they not align with the US government. While Iran’s hardliners consider Europeans and Americans two faces of the same coin, moderates hope that the European business community will be continue to support the narrative that Iran is a country on the rise with an untapped market and a growing middle class and international presence.

Iranian voices

Iranian officials have used the hostility of the Trump administration to fuel their own propaganda – in Ali Khamenei’s words, the United States is “evil” – and stir up nationalistic feelings. On October 14, foreign minister Javad Zaif tweeted in English in support of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Some Iranians, both in Iran and abroad, have stated that they do not support the IRGC, which to them is a conservative and authoritarian force. “Man sepâhi nistam” (I am not a revolutionary guard) was one of the slogans seen on Telegram. Through such assertions, Iranians show they do not accept hardline propaganda, nor Tehran’s participation in regional conflicts. They also demonstrate support for a more open and liberal Iran.

But Iran’s civil society fears that the ongoing tensions with the US will trigger a new round of authoritarianism within the country. The war of words started with Trump could shift President Rouhani away from his promises of liberal reforms – both economic and social – that won him two elections. The same man who has recently reignited the debate about the utility of chanting Iranian Revolution slogans at the end of Friday prayers – “Death to America”, “Death to Israel”, “Death to England”, “Death to al-Saud” – might now have to turn toward conservatives to stay in power.

Today, a number of officials in Iran fear that the aggressive exchanges over Iran’s regional policies and missile programme are only a pretext. The Supreme Leader seems to believe that the new US administration is supporting not only “behavioural change” but also “regime change”.

A middle path that would perhaps ease the tensions could come from the Persian liberalism that has grown over the past decade. The rising middle and upper-middle classes in Iran are yearning for social change and political accountability, and a fairer redistribution of the oil revenues. Iranian authorities will thus have to find a balance between confronting the new Iranian strategy of the US administration and addressing a potential rise of social discontent at home.