The handwritten manuscript of Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables (1862) – from which the blockbuster stage show and numerous movies ultimately descend – has arrived at the State Library of Victoria (its first time out of Europe).

Will a latter-day pilgrimage to Melbourne commence? Or, as philosopher and critical theorist Walter Benjamin famously argued, does mass consumption through endless reprinting, translation and adaptation eliminate the aura around the original work of art – in this case, the manuscript?

The success of recent exhibitions in the National Library’s Treasures Gallery points to the social lives that classic literary works enjoy, lives that in turn prompt a healthy curiosity about what the handwritten manuscript offers that the professional printings and productions cannot.

The encyclopedist of popular science from antiquity, Pliny the Elder put his finger on it in 77AD when he recorded the:

very unusual and memorable fact that the last works of artists and their unfinished paintings … are more admired than those which they finished, because in them are seen the preliminary drawings left visible and the artists’ actual thoughts.

We still value the more intimate insight the unfinished object opens up to us, provided it is a work of genius. We want to admire the aesthetic achievement, to participate in it; but we also want to understand how it came to be. The manuscript, for literary works, is the lifeline, the palpable link, in material form, to the past creative moment when the rough edges were still showing.

In 1976 I first gazed at a literary manuscript, more or less contemporary with Victor Hugo’s, that of my favourite novel Little Dorrit (1855-57) and the so-called Number Plans that Dickens prepared in order to plan the monthly instalments of his long novel.

I’d just written an MA at Melbourne about Dickens, and had dutifully flicked through the neatly printed Number Plans reproduced in some of those mammoth 800-page, closely typeset Penguin paperbacks. For me, they were Dickens. But here, in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, was the physical evidence of something that had not dawned on me.

Subtle changes in ink colour and angled insertions of cryptic plot summaries revealed to me what must have been later additions to the Number Plans that he went back to insert after writing his monthly 32-pages. He entered the details into the Plans so that, say, six months later as he wrote a later instalment, he could conveniently ascertain what he had covered in the earlier one.

How otherwise to keep track of the sprawling novel? How to go on, month-in, month-out, writing those 32 pages, each instalment bursting with energy, each with its own narrative rhythm and thematic development, so that, after 20 of them, the novel could be issued in volume form without further revision or change?

The novel immediately took on another dimension for me.

The manuscript threw light on the effort, on the process of writing, on the felicitous breakthroughs, the cancellations and changes of mind. My literary training had left me wholly unprepared for this Dickens: Dickens the artificer, Dickens the professional who had to write to deadlines to earn his living.

Since then I’ve held a great many literary manuscripts in my hands – by D H Lawrence, Joseph Conrad, the remarkable Jerilderie Letter (What tiny pages! And in whose hand – not Ned’s?) as well as the heavily marked-up and revised newspaper columns passed to the printer for Henry Lawson’s While the Billy Boils (1896). Each one begs the question of its own history of becoming.

The return of research interest since the 1990s in the meanings of the material forms of works (in their manuscripts, their newspaper and book printings), and in the genesis and creative process that these material forms witness, was inevitable. It has been a tonic. If the exhibition at the State Library draws the crowds it will be partly because of the (inevitable) trickle-down effect from this shift in research direction.

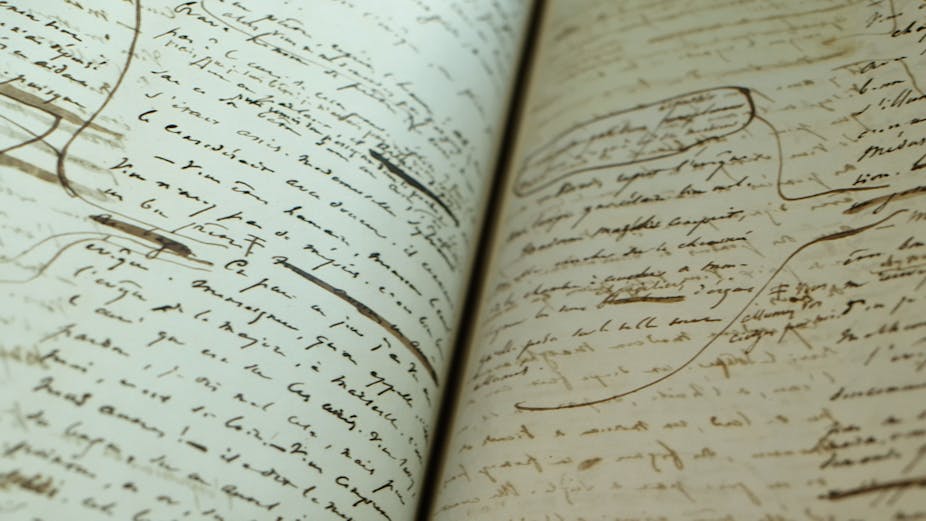

What will the visitors see? On display will be one of the two bound volumes of the manuscript of Hugo’s novel, Les Misérables, written and revised during 1845-48 and 1860-61. He wrote down the right-hand side of each page, leaving the left for later additions and revisions.

And there were plenty. Given the gap between the two bursts of composition, a period in which Hugo’s politics also shifted, rethinking of the novel’s emphases is in evidence everywhere. So too, more subtly, are his stints of writing and the shift in his handwriting characteristics over the 12-year gap; and the hands of his sister and lover also appear.

They, like us, would have felt they had a stake in this literary classic.

Victor Hugo: Les Misérables – From Page to Stage is at the State Library of Victoria until November 9.