To imagine what “Australia” was like B.C. (“Before Cook”, or before colonisation), one needs to envision the entire landmass of this island/continent and most of its surrounding islands and waters as crisscrossed by “Dreamings” (in popular parlance sometimes referred to as “Songlines”).

Each of the approximately 250 separate Australian languages had their own words for and substantial vocabularies relating to what has now become known in English almost universally as “The Dreamtime” or “The Dreaming”. These usages have now entered other world languages as global tags for Indigenous Australian religion, thereby dramatically reducing outsiders’ capacity to grasp the diversity of Australian languages and cultures.

(It should be noted here that “Australian languages” is the linguistically accurate terminology for Aboriginal languages – which have no connection to any other language families in the world. The terminology “Australian languages” also takes on a political edge for Aboriginal language speakers, many of whom regard all other languages spoken in Australia, including English, as foreign imports).

In the Ngunnawal and Ngarigo languages, for instance, in and around today’s national capital, Canberra, The Dreaming is called “Daramoolen”, and it’s “Nura” in the Dharug language, in the vicinity of Sydney.

Across some of the dialects of Western Desert languages, including Pitjantjatjara, which crosses the borders of three states, South Australia, the Northern Territory and Western Australia, the word-concept is “Tjukurpa”. As a result of processes of colonisation, all of these words have been reduced to the catch-all English translation, “Dreaming”, or sometimes, “Dream Time”.

Dreaming cartography

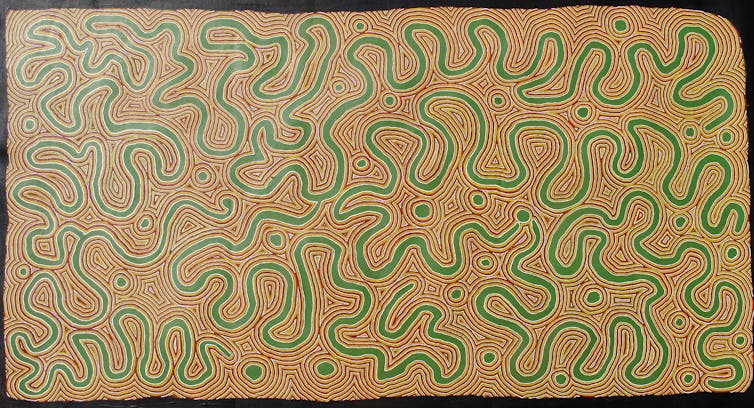

When considering the routes taken by Dreaming Ancestors (Creator Beings, who travelled the country making all things in the natural world, instituting kinship systems and the Law), an apt – though left of field – visual metaphor comes to mind. Diagrammatically, these interconnecting “Dreaming” pathways forged by Creator Ancestors could be represented along the lines of the detailed maps of the London Tube, Parisian Metro, Tokyo Underground, and New York Subway systems, in which myriad transecting lines and stopping points (stations) create complex and intricately imbricated patternings.

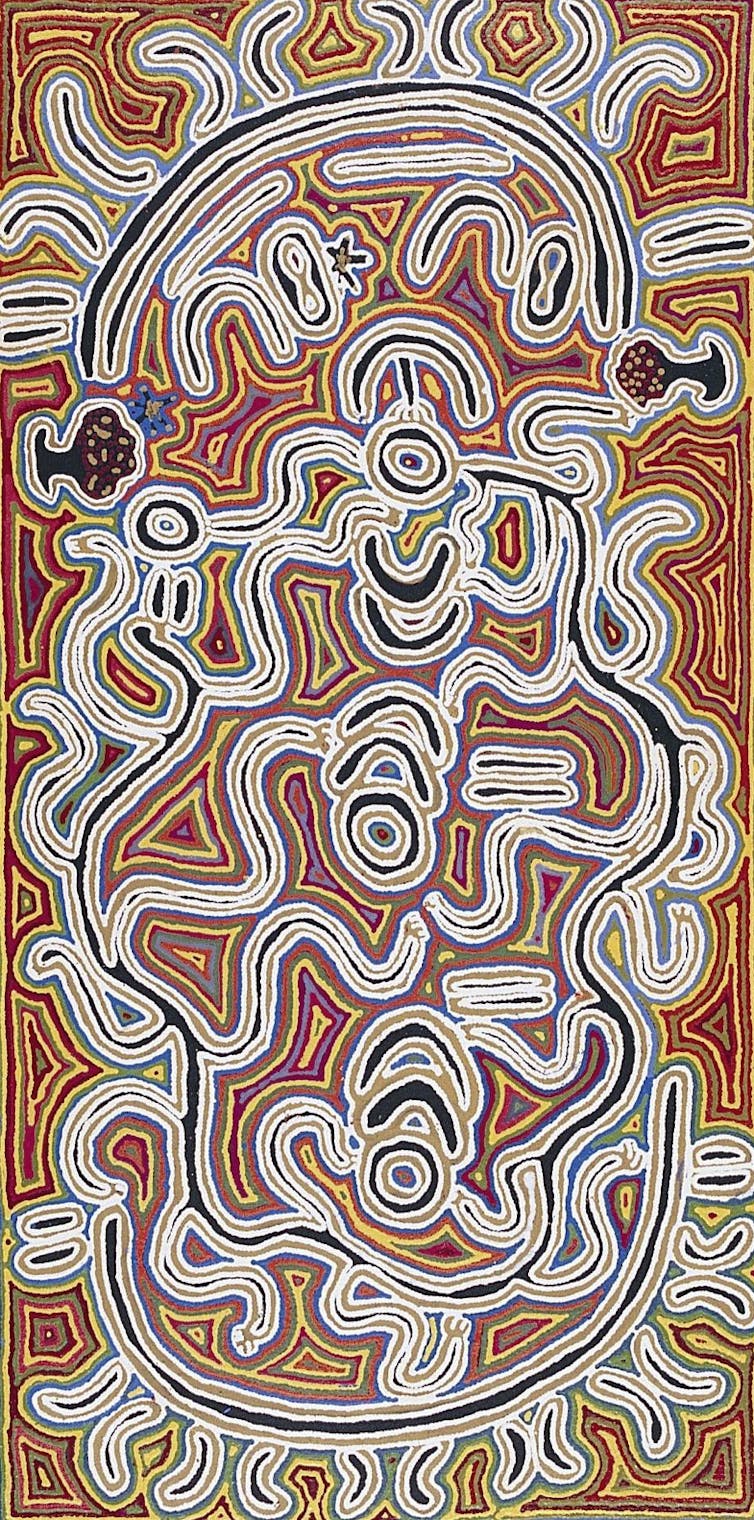

Significantly, akin to those subway networks, interconnected Dreaming sites are named. So, with respect to the Warlpiri artist Shorty Jangala Robertson’s Ngapa Jukurrpa (a “Water Dreaming”), the artwork that heralds this article, the specific named site, Pirlinyanu on Warlpiri country, is traversed by several other Jukurrpa, including the Walpajirri Jukurrpa (Greater Bilby Dreaming; Macrotis lagotis).

Place names may refer to the flora or fauna in a specific place, its above-ground or subterranean water supply, or lack thereof, or allude to significant events that occurred in the narratives framing the specific Ancestral journeys across “country”.

For those wishing to read more about Aboriginal toponymic practices, Luise Hercus and Jane Simpson’s article Indigenous Placenames, an Introduction is a good starting point.

To provide some examples of Warlpiri placenames, Miyi-kirlangu, situated in southern Warlpiri country, translates as “the place of vegetable food”, literally “Vegetable food-belonging”.

Other Warlpiri toponyms include Warlu-kurlangu, to the west of Yuendumu, which means the Place of Fire (literally “Fire-belonging” – kurlangu is a possessive). Today, the ancestral fire that burned across that area has been etched into the landscape itself, in the form of the many large, flame-like anthills on that country.

To this day, viewed from a distance, these ochre-red, flame-like shapes remain potent reminders of the ancestral Jukurrpa fire that swept through that country, dispersing species, taking many lives, including those of the two young men who eventually succumbed to their malevolent father’s powers of sorcery.

The art centre at Yuendumu is also called Warlukurlangu Artists, in recognition of that Jukurrpa. Other significant Warlpiri Jukurrpa sites are closely associated with male initiation, also reflected in their names. Many place names have spatial connotations, assisting people in their rotational navigation around the desert via interconnected sites. The attendant site-specific narratives are committed to memory, enabling precise routes to be framed within broader narrative contexts, which act as mnemonic devices.

Akin to the aforementioned railway networks in high-density areas, in the more highly-populated areas of pre-contact Aboriginal Australia – typically the “country” on which our capital cities are now located – a multiplicity of “Dreaming” intersections crisscrossed one another to create irregular grid patterns.

In arid, outlying areas, such as the Central and Western Deserts, some Dreamings thinned out, but nevertheless continued across the length and breadth of the landmass.

The routes taken by Dreaming Ancestors are memorialised in and on the land itself. As these Creator Ancestors travelled, planting languages into the ground, instituting social, cultural and legal practices, and stopping along the way to create flora, fauna, waterholes, landmarks, and other environmental features, they interacted with other species and with “country”.

Jay Arthur has written extensively about “country”, a widely used word-concept in Aboriginal English:

The words that Aboriginal people use about country express a living relationship. The country may be mother or grandfather, which grows them up and is grown up by them. These kinship terms impose mutual responsibilities of caring and keeping upon the land and people … For many Indigenous Australians, person and place, or “country”, are virtually interchangeable.

Dreaming or Creator Ancestors

As they journeyed through country, across water, underground or through the sky, Dreaming Ancestors or Creator Beings provided models or templates for all human and non-human activity and interactions, social behaviour, natural development, ethics and morality.

While the narratives connecting the travels of these Dreaming Ancestors to specific sites may be sung or spoken, they collectively represent a significant body of oral literature, comparable with other great world literatures, such as the Bible, the Torah, the Ramayana, and the Greek tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles, to name but a few.

Like those aforesaid works, “Dreaming” narratives make little attempt to mask their fundamentally didactic purpose: to teach about the sacred geographies of specific cultural landscapes, that people might learn to live on specific “country” successfully, in accordance with the Law.

Dreaming narratives

The entirety of “country”, including its environmental features, its topography and landmarks, its flora and fauna, its water sources, was (and for many, still is) deeply etched and encoded with meaning, and connected by powerful narratives. “Country”, whether that be terra firma, the sea, freshwater, or the celestial realm, all of which are regarded as animate, living, breathing entities, always has a significant part to play in Dreaming narratives.

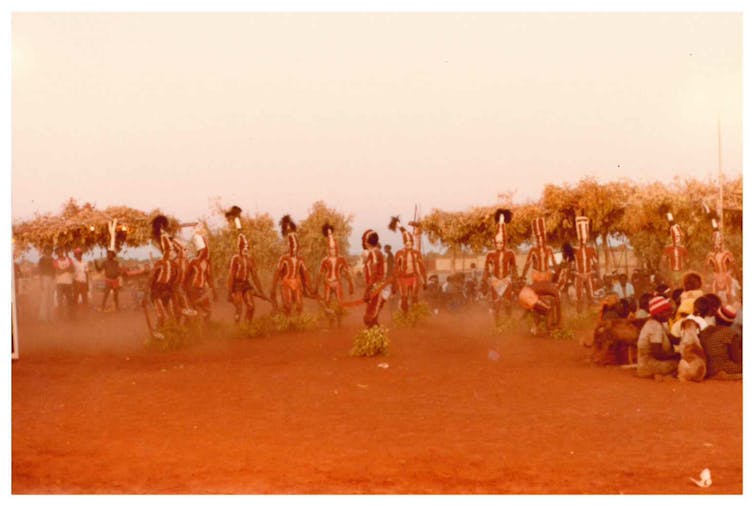

Lengthy narratives, epics expressed visually or through dance and music as well as spoken or sung, provide details about those ancestral journeys through “country”.

The following brief examples of Dreaming narratives from two different places in Australia, Central Australia and Western Arnhem Land, illustrate the nature of Dreaming narratives, and their situated-ness in specific country. This will be followed by a more detailed analysis of two more contrasting Dreaming narratives in the next article in this series.

The Lajamanu-based Warlpiri artist Myra Nungarrayi Herbert/Patrick’s Ngalyipi Jukurrpa (“Bush, Snake or Native Vine Dreaming”) is at one level a visual portrayal of the rope-like vine Tinospora smilacina, a plant that grows on Warlpiri country. Ngalyipi served many purposes in earlier times, ranging from medicinal to ceremonial, the secular to the secret-sacred. In some ways it’s not unlike aloe vera.

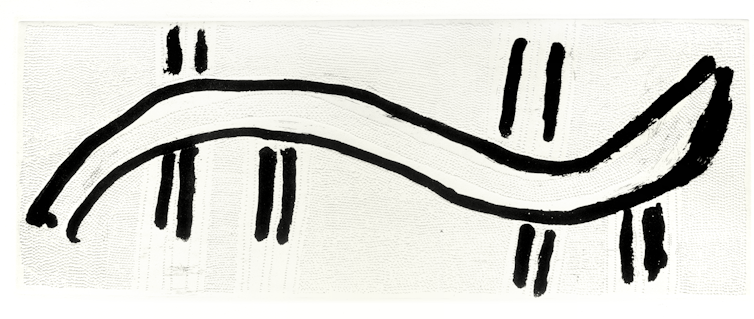

Ngalyipi was used as a poultice to alleviate muscle and joint pain; applied externally to treat gastro-intestinal ailments; rubbed into wounds, boils, infected sores and the like; and taken by mouth to relieve the symptoms of colds, the flu, and related complaints. It was also used as a kind of rope for men to bind leaves to their ankles in public ceremonies called purlapa, and also to tie long, elongated witi poles to men’s bodies in more restricted male initiation ceremonies.

The lengthy narratives relating to these male Witi ceremonies in which ngalyipi plays a role, and the travelling of the men and initiates from Jukurrpa site to Jukurrpa site, may only be divulged to certain senior persons in the appropriate kinship groups.

Some of what one can learn about the nature of Jukurrpa narratives is, however, evident in this brief description. At one level, detailed ethno-botanical knowledge relating to this useful, multipurpose vine is deeply embedded in the narrative, as is Warlpiri medicinal know-how. At the same time more restricted subject matter pertaining to a significant cultural practice informs the longer narrative.

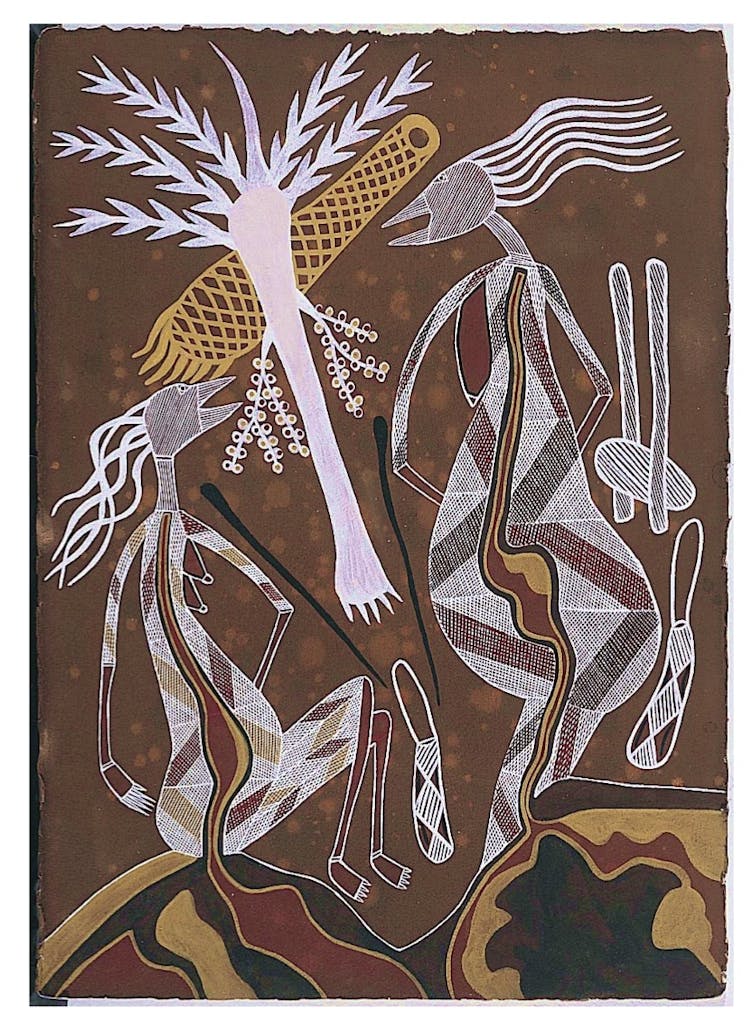

In significant contrast, in terms of both subject matter and stylistic features, there’s Ralph Nganjmirra’s Diarrhoea Dreaming, the title of which may surprise some readers, given existing preconceptions about the unqualifiedly “spiritual” nature of Dreamings and their accompanying narratives.

Nganjmirra is a Western Arnhem Land (Kunwinjku) artist who paints with the Injalak Art & Crafts group at Gunbalanya (formerly known as Oenpelli), not far from Jabiru in Australia’s “Top End”. That “country” is markedly different from that of the Warlpiri desert dwellers.

This Dreaming artwork, as with other Western Arnhem Land painting, shows the characteristic “X-ray” style of that region. Rarrk (clan-owned cross-hatchings, which have been likened to the Scottish tartans in terms of familial ownership of the designs) also characterise artworks from this area.

The narrative relates to the deaths of two Ancestral sisters, both pregnant, who accidentally consumed highly toxic cycad berries and drank salty water. As a result they died very nasty deaths involving dysentery and vomiting (we’ve been spared the vomiting in this artwork – the specific visual information that the artist who is the Dreaming owner chooses to disclose is at his or her discretion).

As is the case with Myra Nungarrayi’s work, Nganjmirra’s narrative operates on several levels. The Diarrhoea Dreaming encapsulates deep knowledge of the properties and location of local flora (ethno-botany, again). It also has a didactic function, that of instructing others about the toxicity of these berries, which is in this case a matter of life and death.

Finally, it offers a commentary on the fatally unwise actions of the two sisters, whose intemperate behaviour led to their premature deaths, and to the deaths of their unborn children. Thus the sisters act as “negative exemplars”, as discussed in part two of this series.

In common with other Dreaming narratives, Nganjmirra’s work has a dimension that cannot be shared with just anybody.

This article is the third in a series on “Dreamtime” and “The Dreaming”. Read part one here and part two here.