In 2002, Jeannie Herbert Nungarrayi, formerly a Warlpiri teacher at the Lajamanu School in the Tanami Desert of the Northern Territory, where I worked for many years first as a linguist and then as school principal, explained the central Warlpiri concept of the Jukurrpa in the following terms:

To get an insight into us – [the Warlpiri people of the Tanami Desert] – it is necessary to understand something about our major religious belief, the Jukurrpa. The Jukurrpa is an all-embracing concept that provides rules for living, a moral code, as well as rules for interacting with the natural environment.

The philosophy behind it is holistic – the Jukurrpa provides for a total, integrated way of life. It is important to understand that, for Warlpiri and other Aboriginal people living in remote Aboriginal settlements, The Dreaming isn’t something that has been consigned to the past but is a lived daily reality. We, the Warlpiri people, believe in the Jukurrpa to this day.

In this succinct statement Nungarrayi touched on the subtlety, complexity and all-encompassing, non-finite nature of the Jukurrpa.

The concept is mostly known in grossly inadequate English translation as “The Dreamtime” or “The Dreaming”. The Jukurrpa can be mapped onto micro-environments in specific tracts of land that Aboriginal people call “country”.

As a religion grounded in the land itself, it incorporates creation and other land-based narratives, social processes including kinship regulations, morality and ethics. This complex concept informs people’s economic, cognitive, affective and spiritual lives.

Everywhen

The Dreaming embraces time past, present and future, a substantively different concept from populist characterisations portraying it as “timeless” or having taken place at the so-called “dawn of time”. Unfortunately, even in mainstream Australia today, when and where we should know better, schmaltzy, quasi-New Age notions of “The Dreaming” frequently still hold sway.

The Australian anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner conveyed the idea more accurately in his germinal 1956 essay The Dreaming, in which he coined the term “everywhen”:

“One cannot ‘fix’ The Dreaming in time: it was, and is, everywhen” wrote Stanner, adding that The Dreaming “ … has … an unchallengeable sacred authority”.

Stanner went on to observe that: “We [non-Indigenous Australians] shall not understand The Dreaming fully except as a complex of meanings” (my emphasis).

It isn’t possible here to offer more than an introductory glimpse into that constellation of meanings, any more than it would be to convey anything approaching a comprehensive understanding of other world religions in a brief article.

Words in Aboriginal languages for and about the concept of “The Dreaming”

B.C. (“Before Cook”) there were approximately 250 separate Aboriginal languages in what is now called Australia, with about 600-800 dialects.

It’s apposite and relevant to map Australia’s considerable geographical and environmental diversity onto this high level of linguistic and cultural diversity. Therefore it won’t be surprising to learn that there is no universal, pan-Aboriginal word to represent the constellation of beliefs comprising Aboriginal religion across mainland Australia and parts of the Torres Strait.

Unfortunately, since colonisation, this multiplicity of semantically rich, metaphysical word-concepts framing the epistemological, cosmological and ontological frameworks unique to Australian Aboriginal people’s systems of religious belief have been uniformly debased and dumbed-down – by being universally rendered as “Dreaming” in English – or, worse still, “Dreamtime”.

Neither passes muster as a viable translation, despite the fact there’s an element or strand in Aboriginal religion that does relate to dreams and dreaming.

As Maggie Fletcher (now visual art curator at the Adelaide Festival Centre) wrote in a 2003 Master’s thesis – for which I was the principal supervisor – “Dreaming” Interpretation and Representation:

… an entire epistemology has been reduced to a single English word.

Not only that, words from many different languages have been squished into a couple of sleep-related English words – words that come with significantly different connotations – or baggage – in comparison with the originals.

As noted earlier, the Warlpiri people of the Tanami Desert describe their complex of religious beliefs as the Jukurrpa.

Further south-east, the Arrerntic peoples call the word-concept the Altyerrenge or Altyerr (in earlier orthography spelled Altjira and Alcheringa and in other ways, too).

The Kija people of the East Kimberley use the term Ngarrankarni (sometimes spelled Ngarrarngkarni); while the Ngarinyin people (previously spelled Ungarinjin, inter alia) people speak of the Ungud (or Wungud).

“Dreaming” is called Manguny in Martu Wangka, a Western Desert language spoken in the Pilbara region of Western Australia; and some North-East Arnhem Landers refer to the same core concept as Wongar – to name but a handful.

Satellite terminology for understanding “The Dreaming”

As with other world religions such as Christianity and Judaism, there is an extensive, closely affiliated ancillary vocabulary complementing the central Indigenous term – that is, accompanying each specific Aboriginal language group’s name for their religion.

In the case of the Christian religion, word-concepts such as Holy Trinity; Advent; Ascension; Covenant; Pentecost; apostle; baptism and so forth, ideas with which many readers will be familiar, are also germane to coming to a deeper understanding of that religion.

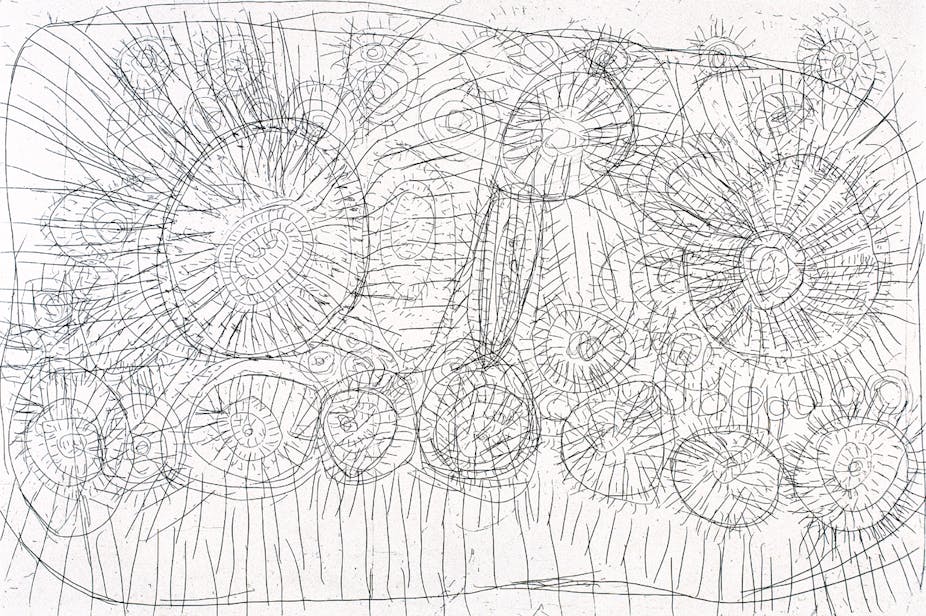

So it is with Aboriginal religious belief. The Warlpiri religion, the Jukurrpa, has a host of word-concepts that are important adjuncts to the core concept. Included among these is kuruwarri, defined in the Warlpiri dictionary as:

visible pattern, mark or design associated with creative Dreamtime (Jukurrpa) spiritual forces: the mark may be attributed to these forces, or it may symbolise and represent them and events associated with them; mark, design, artwork, drawing, painting, pattern.

Pirlirrpa is defined as “the spirit, the soul, the person’s essence”, and is believed to reside in the kidneys; yiwiringgi is a person’s Conception Dreaming, defined in the Warlpiri dictionary as an individual’s:

life-force or spirit which is localised in some natural formation and which may determine the spiritual nature of a person from conception and the relation of that person to the life-force.

Or, in lay terms, closely related to the place where the mother believes she conceived the child. As Warlpiri man Harry Nelson Jakamarra – also in the Warlpiri dictionary – further elucidates, a child’s Conception Dreaming derives from the location where the mother believes her child to have been conceived:

… Kurdu kujaka yangka palka-jarri, wita, ngapa kuruwarrirla marda yangka wiringka, ngula kalu ngarrirni kurdu yalumpuju Ngapa-jukurrpa. Yalumpu ngapangka kuruwarrirla kurdu palka-jarrija.

(“When a baby is conceived, it might be in an important Rain Dreaming place, then they call that child Rain Dreaming. The child came into being in that Rain Dreaming site”).

Another key word in relation to the Jukurrpa, kurruwalpa has been defined by the Polish-French anthropologist Barbara Glowczewski as:

the spirit-child which, returning to the site where it had entered its mother, waits to be reincarnated into another child-to-be-born.

There are numerous other associated word-concepts too, all relating to the central idea of the Jukurrpa, some of which are too sacred or gender-specific to reveal.

A challenge for all Australians

Also akin to mainstream world religions, while these geographically and doctrinally diverse Indigenous Australian religious concepts do have a level of commonality – as is demonstrably the case with different denominations and branches of Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and so forth – these Aboriginal religions cannot be regarded as monolithic entities.

Analogous with Christianity, in which there are doctrinal differences affecting the beliefs and practices of those who adhere to Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox or Coptic branches of Christianity, Indigenous regional and cultural differences need to be taken into account in order to develop a real understanding of the religion known in English as “The Dreaming”.

But what differentiates Aboriginal religion from other religions is its continuity with local landscapes or what Indigenous artist Brian Martin has described as “countryscapes”.

Dreamings, founded upon the actions of Dreaming Ancestors, Creator Beings believed responsible for bringing-into-being localised geographical features, land forms such as waterholes and springs, differ across the length and breadth of Australia. (For obvious reasons, there’s no Oyster, Stingray, Shark, Octopus, Squid or Saltwater Crocodile Dreaming in Central Australia).

The universal translation of these terms as “Dreaming” needs to be questioned. If Australia is to grow as a nation, to make right the relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians, it’s time to start using the original terminology from Indigenous languages, to learn how to pronounce the words, and to talk about the Manguy, Jukurrpa, or Ngarrankarni, in place of the catch-all “Dreaming”.

It’s a more difficult path, but could also teach the rest of us a thing or two about Indigenous cultural, linguistic and religious diversity.

This article is the first of a series on “Dreamtime” and “The Dreaming”. Read part two here and part three here.