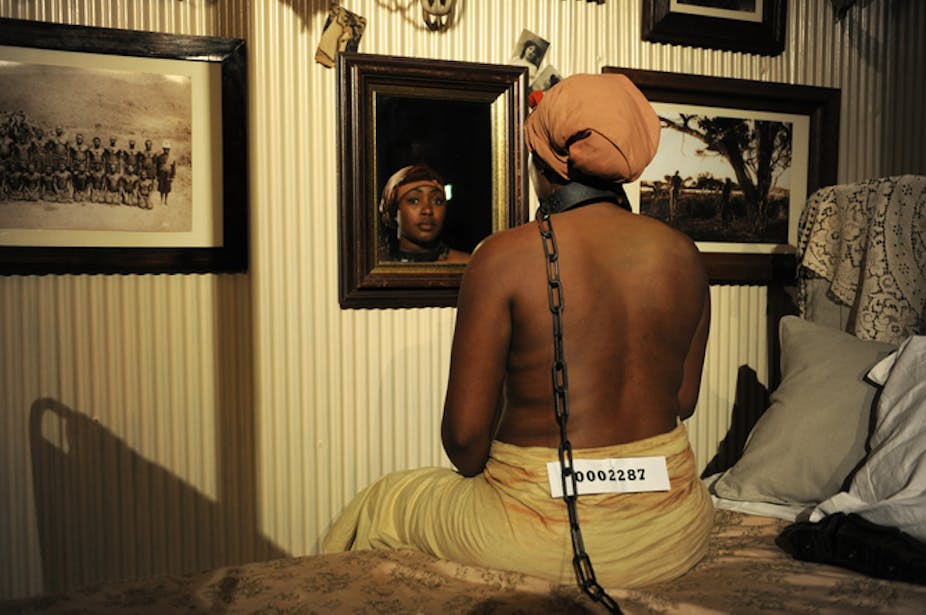

A large group of protesters have successfully shut down an exhibition in London. Curators intended Exhibit B, a “human zoo” comprising caged and chained black actors, to demonstrate the evils of slavery. Protesters were justifiably angry that such problematic and insensitive portrayals are still being staged. This only serves to underline the importance of exactly how histories are collected and curated – both who by and for whom.

As such, the Black Cultural Archives (BCA), which opened with deserved fanfare this summer, is an institution that is long overdue in London. It joins an increasing number of organisations, which collect and promote material relating to people of African descent that includes Washington DC’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Such institutions bring together the histories of people too often left out of national museums, and whose lives are only recently being documented and collated in any organised way. The archives are a testament to grassroots’ level commitment to collecting, documenting and celebrating the African-Caribbean diaspora and its legacies.

The BCA is located within the heart of a multi-cultural community – one that has been active in donating and supporting the archive’s foundation. The growth of Brixton’s black population in the post-war period has spawned a diverse and ethnically rich mix that is evident in, for example, the district’s retail and entertainment culture, but has also at times seen it become a flashpoint for racial tensions. The BCA sits therefore at the nexus of community, politics and race. The centre both formalises black British histories and makes their importance known – through the bricks and mortar of its institution, as well as its myriad holdings.

This is demonstrated through its varied programmes – targeted at everyone from “the Elders of the community” to schoolchildren. It makes available its material and visual evidence through workshops, exhibitions, films and walking tours.

It’s the importance of representation – literally and metaphorically – that is at the heart of this enterprise. You are seen by the wider population and the media a certain way, but you also make yourself visible, assert identity through clothing choices. Considering this double meaning of visibility allows us to think about fashion’s connections to the grand narratives of race and politics. Brixton’s archive, and others like it, set out to undercut and make these narratives more complex. They attempt to broaden our understanding, rather than to simply shock – like Exhibit B.

This is important because representing diversity is not enough – showing the diversity within what we understand as “diverse” communities is needed too. As Nina Cartier of Northwestern University recently wrote, we need to move away from binary oppositions and stereotypes of black women. While Kerry Washington’s portrayal of Olivia Pope in Scandal and Nicki Minaj’s stage personae open up important debate, and show the role of pleasure and sexuality in popular culture, she stresses that more choices, more kinds of black women (and men) need to be seen.

Real diversity

And this is exactly what the BCA’s inaugural exhibition offers. It features snapshots of black women’s lives, activism and contribution to British history since the 17th century.

This includes photographs of pioneering journalist Una Marson, entertainer Adelaide Hall, and video and posters that relate to black feminism in the 1970s. In each image, the significance of clothing, hair and accessories choices reminds viewers of their role in creating identities that assert and perform women’s professional, political and personal roles.

The balance between micro and macro histories and the links these make between local and global communities is fundamental to developing the study of black histories. You only need to look at the web pages covering the BCA’s collaborative five-year project with the V&A, a photograph collection documenting the black British experience between the 50s and 90s, to see this. There are Gavin Watson’s photographs of young skinheads, showing teenage black and white boys hanging about in fields in High Wycombe in Harrington jackets and DM boots, or shaving their hair in the requisite style. And in Normski’s work the wide range of fashions worn, the transnational references to African and Caribbean styles and American hip hop, as well as contemporary street styles and the ordinary, everyday dress of the day are what is at the fore.

When Lois K Alexander-Lane, founder of the Black Fashion Museum Collection, was a student in New York in the late 1930s, and wanted to write about African-Americans’ contribution to fashion and retail history, her tutors told her that there was no such thing to be studied. What the BCA and related international collections show is the huge wealth of black histories still to be told. We should move away from shows such as Exhibit B. Finally, there is a formal context in which to contemplate the role and contribution of diverse African-Caribbean peoples to global development.