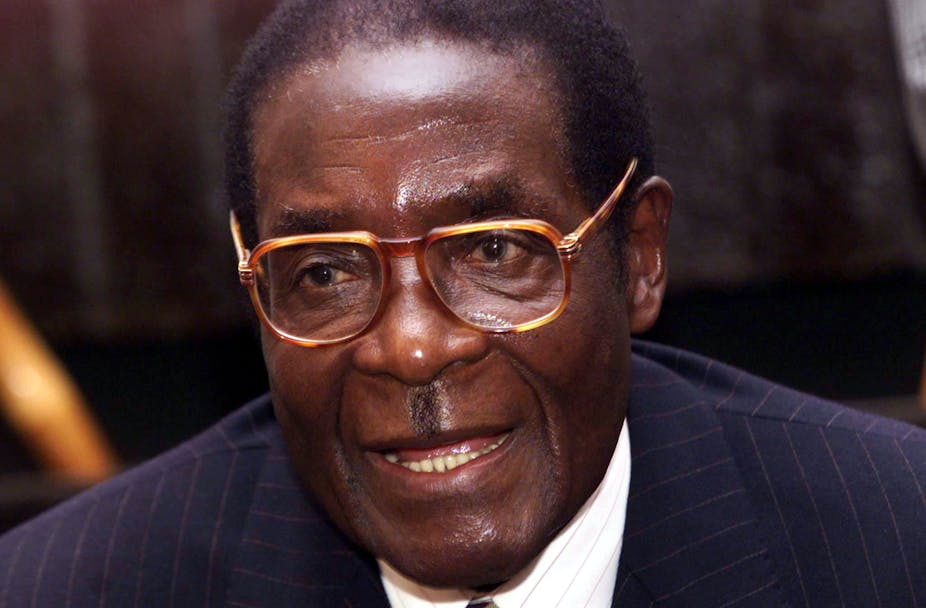

Robert Mugabe spoke eloquently as Zimbabwe’s Prime Minister Elect in March 1980. He offered a message of hope and unity to a population ravaged by years of war. He spoke of creating a government “capable of achieving peace and stability … and progress.”

In the first years of independence, some of this vision was realised. But in the ensuing decades peace, stability and progress have waned. Mugabe has been in power for 36 years. The country’s political environment is unstable at best. Its economy is in ruin. There is no clear succession plan.

Mugabe’s presidency has been characterised by mismanagement, corruption, and control over dissent and debate. Outsiders might not understand how someone who led his country’s downfall from breadbasket to basket case has remained in the presidency for so many years.

So who is Robert Mugabe and how has he held onto power for so long?

Colonial childhood

Growing up under colonial rule made a large impact on a young Mugabe. Colonialism in what was then Rhodesia started in 1889 when the Crown granted the British South Africa Company a Royal Charter that gave rights to the land which later became Northern (Zambia) and Southern (Zimbabwe) Rhodesia.

The charter gave the British South Africa Company the power to expropriate land and encourage British settlement to exploit the territory’s resources. It declared Southern Rhodesia a colony in 1896, prompting the First Chimurenga, which saw the Shona and Ndebele defeated.

The British South Africa Company introduced commercial agricultural development after discovering that the colony was not rich in gold. Commercial farming was dependent on the expropriation of land from the rural population. So in 1898 it encouraged expropriation for commercial agricultural production of tobacco, maize, and corn. It also set up a reserve system which aimed to move and concentrate Shona and Ndebele populations into so-called native reserve lands.

This set the stage for Mugabe’s childhood and the ideology behind the Second Chimurenga, in addition to much of Zimbabwe’s current inequality.

A political education

Mugabe was born on February 21, 1924 in Kutama a few months after Southern Rhodesia became a self-governing British Crown colony.

Unlike most of his compatriots who received a grammar school education at best, Mugabe was lucky enough to receive a very good education. The young boy’s intelligence made him stand out amongst his peers, and he was offered a place to study at the elite St. Francis Xavier Kutama College. Mugabe went on to qualify as a teacher at Kutuma College.

He received a scholarship to South Africa’s Fort Hare University. There he met future leaders like Julius Nyerere from Tanzania and Kenneth Kaunda from Zambia. He joined the African National Congress. He was also exposed to Marxism. After graduating in 1951 with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in History and English, he taught in several schools and continued his studies in Southern Rhodesia and Tanzania, where a nationalist movement led by Nyerere was starting to form.

Mugabe’s political ideology solidified after moving to newly independent Ghana to teach in 1957. Ghana was the first British colony to gain independence in Africa. Kwame Nkrumah’s socialist and anti-imperial rhetoric struck a chord with Mugabe, who by this time was active within Ghana’s political youth leagues.

Mugabe met his future wife Sally Hayfron in Ghana. They travelled to Southern Rhodesia in 1960 so she could meet his mother – and found a very changed place.

The settler population had increased, and with it the displacement of people and the overcrowding of the reserves. Unemployment was high and most people had no opportunities for advancement.

The government of Southern Rhodesia cracked down heavily on dissent at this time. After several opposition leaders were arrested under the 1959 Unlawful Organisations Act, Mugabe addressed a crowd gathered at Harare Town Hall. He spoke about Ghana’s independence movement. In referring to Marxism and its tenets of equality, he offered an alternative future to a crowd frustrated by minority rule.

Mugabe’s political career had begun.

Towards independence

Mugabe was elected Secretary of the National Democratic Party (NDP). Ten days after the government banned the NDP in 1961, several leaders came together to form Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), which was led by Ndebele trade union leader Joshua Nkomo. Mugabe, ZAPU’s Information and Publicity Secretary, was frustrated with Nkomo’s approach and felt that his demands for majority rule favoured rhetoric over action. Other leaders felt the same way and they together broke from ZAPU to form Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) in 1963.

The government banned both ZANU and ZAPU and several party leaders, including Mugabe, were imprisoned in 1964 – the year Ian Smith became Prime Minister.

Smith would not agree to a plan or timetable for majority rule in Southern Rhodesia. He unilaterally declared independence from Great Britain in 1965, prompting sanctions and isolation from the international community.

During his ten years in prison Mugabe remained active in ZANU politics. In 1974 he was elected ZANU party head in what some argue was a coup against sitting leader Ndabaningi Sithole. In 1974, at the insistence of South African leaders, Smith released Mugabe to attend a conference in Zambia. Mugabe fled to Mozambique where Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) guerrilla forces were being trained for what would be another five years of war.

In December 1979 the Lancaster House Agreement formalised a ceasefire and set the path for Zimbabwe’s independence. Mugabe was named Prime Minister in February 1980 elections and the international community recognised Zimbabwe’s independence on April 18, 1980 amid much hope and optimism.

A promising beginning

But distrust and insecurities remained. The white minority population was afraid that Mugabe’s government wouldn’t abide by the terms of the Lancaster House Agreement. They also worried about land expropriation and that civil servants would be denied their pensions. But Mugabe preached reconciliation.

The first decade of independence saw the building of that great Zimbabwe which Mugabe spoke about before independence – at least in terms of some important economic and human development gains. The country garnered a reputation as southern Africa’s breadbasket, feeding itself and other countries in the region.

Mugabe continued to recognise the importance of education: the government’s investments resulted in education and literacy rates that were admired throughout the continent. A thriving civil society spearheaded community development efforts throughout the rural areas, where much of the population felt connected to the leader who promised, and seemed to deliver, development.

But when people look back now on Mugabe’s presidency they will not necessarily remember any of these positives. His legacy will be very different.

A grim legacy

People will remember a leadership style that silenced opposition and ultimately led to sanctions against the country and its leaders. This began as early as the 1980s when the Special Forces Fifth Brigade, purportedly trained in North Korea, led a series of raids on Ndebele opposition areas that resulted in the deaths of at least 10,000 “dissidents.”

The merger of ZANU and ZAPU into ZANU-PF effectively institutionalised a system without opposition, in a country where state run media dominates.

People will remember how Mugabe was able to shift his alliances and alienate opponents throughout his political career. They will remember the rampant corruption and patronage and the falling incomes and high unemployment rates. People will remember how Mugabe used land reform for political expediency.

Zimbabwe’s challenges today are probably vaster than they were at independence. Corruption is institutionalised, and that is not going to change easily. Investor confidence will take time to recover, as will income levels. There is no clear path for the democratic succession of a leader.

Land reform is at the heart of modern Zimbabwe’s political and economic challenges. It has been haphazard and mismanaged at best. At worst, violent, corrupt and unproductive. Legal and meaningful land reform is paramount. This is only likely to happen with the institution of good governance in Zimbabwe. This is something that could be years in the making – even without Mugabe occupying the office of the president.