There’s a problem with the history of western art: we face it from the wrong side of decades of discursive dismantling.

The conventional “story” of early 20th-century modernism, in which an advanced guard of painters moved towards greater forms of abstraction, seems so thin today, so limited in its scope, and so completely mired in gender and material prejudices.

The canonised version of cubism

The cubism that was canonised in art history, and the version that was said to be the most authentic, the most progressive, was brought into being by two men: Spaniard Pablo Picasso and Frenchman Georges Braque.

There were two stages of development:

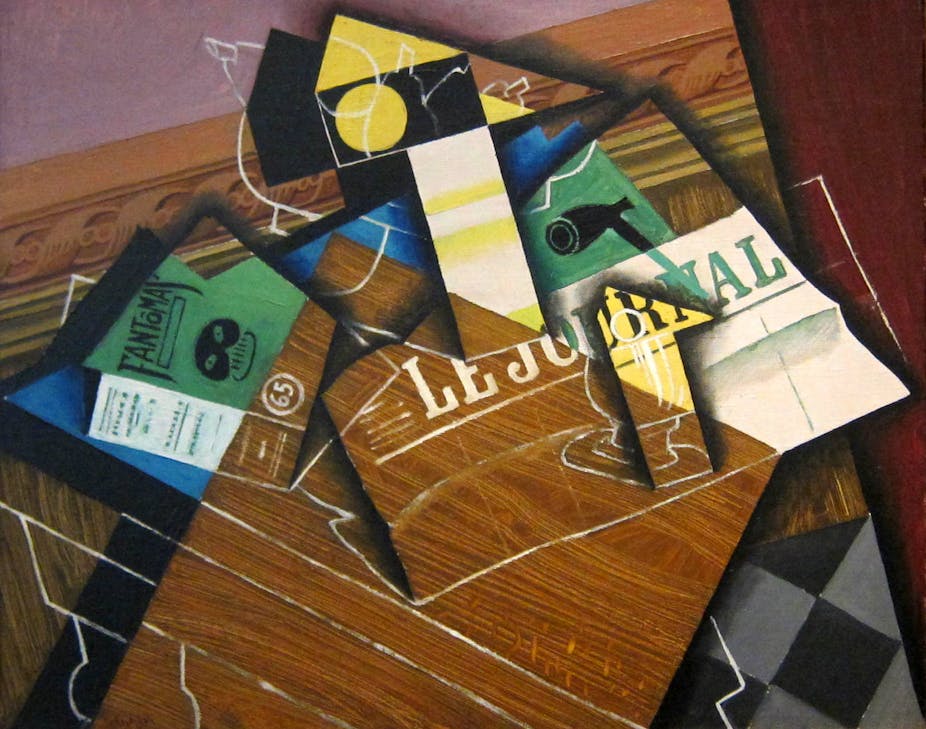

- “Analytical cubism”, in which a three-dimensional object was flattened across a two-dimensional plane, such as Braque’s Bottle and Fishes (1910).

- “Synthetic cubism”, which adopted methods of collage, using newspaper print, such as Picasso’s Bottle of Suze (1912).

Such dismantling of figure, ground and perspective represented, so the story went, the gradual dissolution of realism and single point-perspective initiated in Renaissance Italy centuries earlier.

Within the boundaries of such tidy logic, we might also think of these two innovators as forming a brilliant omphalos (or centre) from whence cubist-like work spread outward on concentric waves of adulation. Finally, the purity of these first acts had been so “diluted” that its spirit was destroyed.

This notion of progressive art history was finally arrested by a diverse group of opponents in the decades following the second world war: feminists, conceptual artists and minimalists, Marxists, those interested in non-Western forms of practice, others bored with the dominance of painting, video artists, performance artists, those wanting to challenge an over-reliance on aesthetics, those concerned with questions of politics or social context, and so on …

If the first act that diluted cubism was stylistic, the second was definitely political.

In its time, cubism seemed difficult and wild, and it was a favourite target of conservatives. It was often dispelled as a failure of vision, even of sanity, and was judged by many observers as a sign of a civilisation in decline.

The fascists and the communists, famous as they are for rejecting abstraction for pastoral realism or socialist realism, were not the only detractors.

In 1946 (the date is significant I think for coming after the holocaust), the Australian academic-artist and writer Lionel Lindsay published a notorious anti-Semitic rant, Addled Art, blaming Jews for flagrantly placing mercantile interests over “proper” art in the promotion of cubism.

It’s still a shocking and strangely incoherent text to read today, but it stands for another rich vein of criticism that helped bolster cubism’s original reputation as a progressive movement.

There’s more to cubism than Braque and Picasso

The canonised version of cubism placed a concern for the formal qualities of artwork over all other factors. This move, known as “[formalism](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Formalism_(art)”, hermetically sealed off cubism from the complicated net of influences that had brought it into being.

Cinema, montage and French philosopher Henri Bergson’s ideas on duration represented common points of influence in a wider desire to capture and understand time (the response of cubism would be seen as the capturing of an object from all of its possible perspectives).

Also, the politics of class and imperialism, and the pivotal role of women artists (marginalised later in a largely patriarchal discipline) are easily discovered in contemporary accounts of early avant-garde practice.

Let’s end, therefore, with this homage to Jewish-French-Russian artist Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979). I think of her as a kind of hinge holding together diverse avant-garde artists, poets and designers from across Europe.

She and her fellow artists developed a method of abstraction called “orphism”, sometimes called “orphic cubism”. Named by her friend, the poet, critic and mouthpiece of cubism, Guillaume Apollinaire, orphism was an experiment with the simultaneous affect of colour and form to make a surface appear to vibrate.

It was Delaunay-Turk who financially supported the family, which included her painter husband Robert Delaunay, by expanding her experiments into other directions and other media.

She transposed her painting ideas onto the making of a quilt for her son, collaborated on a work with the Swiss-born poet Blaise Cendrars, designed costumes for Dada plays, decorated cars, worked as a set designer for films and plays, and opened clothing ateliers. She was well enough considered in 1927 to give a lecture at the Sorbonne on the relationship of painting to fashion.

Sonia Delaunay-Turk lived until 1979, and yet, a scant few decades ago, she couldn’t be found in compilations of modern artists, nor has she moved very far today from marginalised status.

At the time, she was at the centre of avant-garde challenges to bourgeois aestheticism, for which the Picasso-Braque version of cubism formed only a small part.

See also:

Explainer: what is modernism?

Explainer: what is postmodernism?