Many first responders’ – even some university police officers – are carrying a new tool in their first-aid kits. It’s naloxone, the opioid overdose antidote drug, and today it’s more widely available than ever. Naxolone can seem like a miracle drug when administered to an OD'ing patient. How does it work?

In the US, we are facing an opioid and chronic pain epidemic. Opioid prescriptions have increased 300% over the past 20 years with opioid overdose deaths quadrupled in parallel. The latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tell us that prescription opioids – pain relievers like morphine, methadone, hydromorphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydrocodone – were responsible for 16,917 overdose deaths in 2011, and deaths from heroin doubled from 2,089 in 2002 to 4,397 in 2011. More recently CDC reported that in 28 states death rate for heroin doubled from 2010-2012 with a small decline in deaths from opioid pain relievers.

High doses of opioids put the breathing center in the brain to sleep, leading to loss of consciousness. Breathing slows and then stops. In use since the 1970s, naloxone saves lives by quickly reversing these deadly effects. As

Opioids mimic natural neurotransmitters

Opioids are powerful chemicals. On the one hand they can relieve pain and suffering, while on the other they can cause tragedy. Opioid drugs reduce the perception of pain and stimulate pleasure and a sense of well-being.

Opioids are effective because they resemble a type of chemical messenger naturally found in the brain and spinal cord. These neurotransmitters, called endorphins and encephalins, do two things. They block pain transmission by binding to the opioid receptors of specialized nerve cells, and they promote euphoria by binding to cells in the reward center of brain.

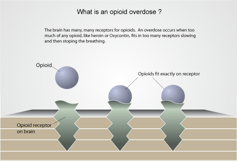

This is your brain during opioid overdose

When external opioids are taken in too large amounts, receptors are overwhelmed in the part of the brain that controls breathing, an area called the medulla oblongata. Breathing slows down to a critical level and then stops. Death follows.

Signs of an overdose include pinpoint pupils, pale skin, limpness, lack of response to painful stimuli and slow pulse and breathing. As the overdose progresses, fingernails and lips may be blue and skin becomes blue or ashen. Breathing sounds like snoring or gurgling and then ceases. Within a short period, the heart may stop pumping blood. After about five minutes starved of blood, serious damage to the brain, heart and other organs occurs.

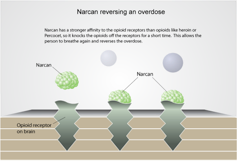

Naloxone works its magic

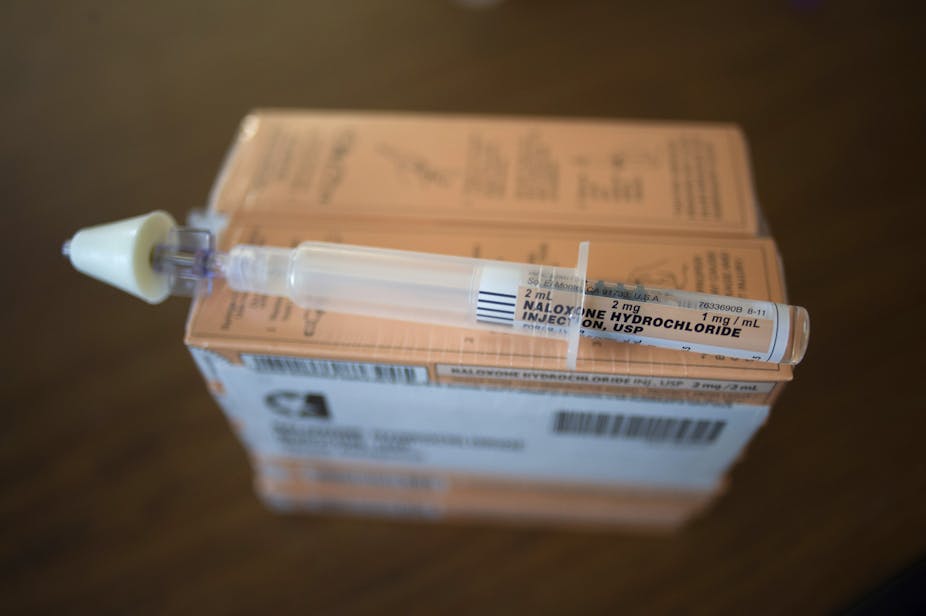

Naloxone is an antagonist to opioids; it counteracts them by blocking receptors. Commonly known by its trade name, Narcan, it can be injected into the vein (IV) or muscles (IM), or sprayed intra-nasally (IN). It can even be self-injected intramuscularly or subcutaneously using the recently-FDA-approved Evzio, a delivery system with voice instructions that is marketed to opioid users and their social network themselves.

Naloxone passes into the blood stream and travels to the medulla oblongata. Naloxone’s chemical shape is a perfect match for the brain’s opioid receptors. In fact, it has an even greater affinity for these receptor sites than the opioids themselves do. So when naloxone hits the brain, it competes and shoves loose the opioids that are suppressing breathing. Usually within a few minutes breathing is restored.

After administration of naloxone doses ranging from 0.2mg to 2mg there is a dramatic restoration of vital signs and reanimation. Patients seem to miraculously come back to life, sometimes jumping up off the stretcher in the ER, as if nothing had ever happened. Patients who had been on the brink of death can be upset that they were given naloxone and want to be discharged. Since naloxone triggers withdrawal, individuals often awaken abruptly and agitated. This effect is more common with the IV formulation than the intra-nasal version. Another advantage of the nasal spray is the avoidance of a needle stick.

The effect of naloxone peaks within two to five minutes and lasts from 30 to 90 minutes. It is important that medical assistance is summoned when naloxone is used, because a positive response may be short lived. Many opioids – like methadone, extended release oxycodone (oxycontin) and hydrocodone (zohydra) – are longer acting and may require repeated or increase doses of naloxone. And many opioid overdoses involve alcohol and other drugs that are not responsive to naloxone. These instances in which naloxone may not work immediately or fails to reverse an overdose require that bystanders institute rescue breathing and call a universal access number such as 911 for medical assistance.

Distributing naloxone

There’s currently a major effort to put naloxone in the hands of first responders: EMTs, police and firefighters, and the lay public. As of August 2014, 25 US states and the District of Columbia have amended their laws to allow physicians to prescribe and dispense the drug and to allow the lay public to administer naloxone without legal consequence. Twenty states and DC have amended or enacted Good Samaritan Laws to allow bystanders to summon medical assistance without legal repercussions.