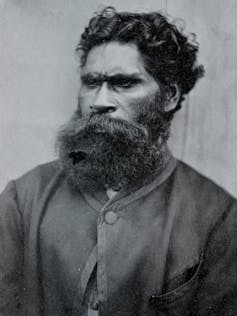

A painting by Wurundjeri artist William Barak was auctioned last week for A$512,400. This set a new record for the 19th century artist, diplomat and leader. (His work had previously reached A$504,000 at auction in 2009).

The auction by Bonhams of the artwork called Ceremony took place in Sydney on 7 June, and the buyer remains anonymous. The previously unknown piece had remained in the family of English craftsman Frank Piggott Webb for over 100 years.

As one of only a few 19th century Aboriginal artists, each piece of Barak’s artwork holds incredible significance for Aboriginal people in Victoria today.

Before it was sold, a group of Barak’s descendants from the Wurundjeri Council had crowdsourced donations in the hope of purchasing Ceremony. They did not manage to raise the required amount and are said to be “shattered” by the auction result. Said Wurundjeri Elder Annette Xiberras:

That painting there showed you how we painted ourselves, it showed you the clothes we wore, it showed possum skin drums. How many people knew our women played possum skin drums? It was so important the stories there. It’s just another little bit of my culture, another little bit of my people that someone has taken from me.

Barak’s artworks are significant expressions of culture for Wurundjeri people. According to the crowdsourcing campaign, as pieces of history they’re “more than art”. For the buyer too, no doubt the history connected with the artwork was a major draw card. The relatively small size of Barak’s oeuvre also increases the appeal of Ceremony: currently only 52 works are known to exist – though others are rumoured.

In the 1890s English glass engraver Frank Piggott Webb acquired Ceremony directly from Barak in exchange for one of his glass works. Webb married an Australian embroiderer and settled in Sydney. The painting by Barak remained in the family, unknown to the art world until recently.

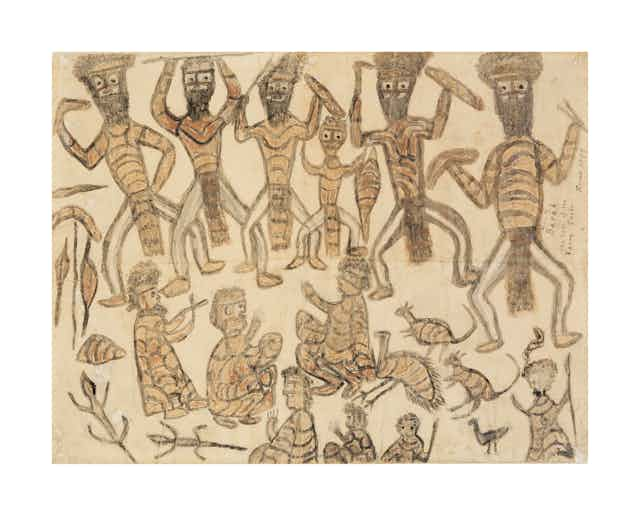

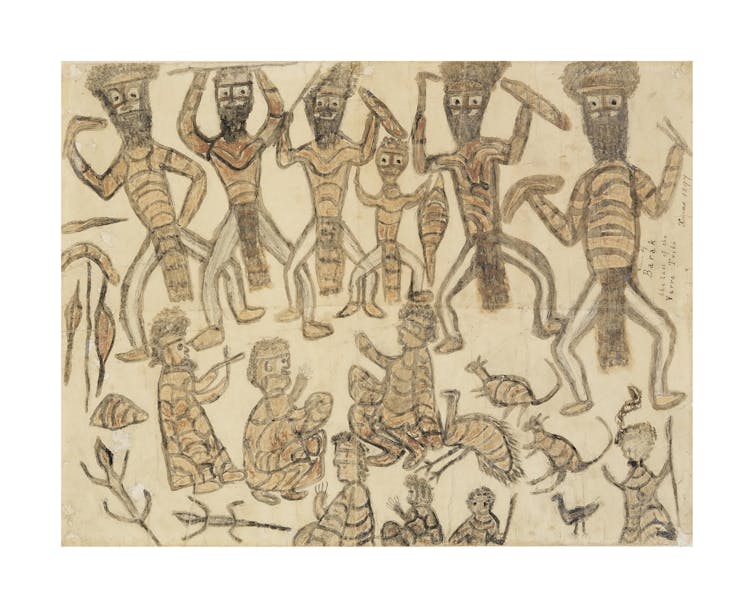

Barak painted for a short period between the 1880s and 1903. His paintings, which could also be described as drawings, were executed using a range of materials and pigments including ochre and charcoal with gouache and pencil on paper. Ceremony is typical in this way, and in size too it is average. Barak’s paintings range in size from less than A4 to almost one metre in length.

The most striking thing about Barak’s work is the figures. In Ceremony six men stand posed in a line holding boomerangs and parrying shields. They’re full of dynamism despite the faded condition of the painting. The men are of different heights and near the centre is a shorter male, possibly an initiate as he lacks a beard. In front of these Elders sit a group of women and children keeping time on possum skin drums. The ceremony leader can be identified on the left keeping time with clap sticks.

In the space remaining, Barak has included more Kulin weaponry as well as a series of birds, marsupials and reptiles. The most striking of these are the emu, kangaroo and goanna. Barak has also included details in the cloaks and weaponry markings; we see a zigzag pattern on the shields and the possum pelts form asymmetrical patterns. An inscription on the right of the artwork informs us that this piece was “drawn by Barak the last of the Yarra Tribe, Xmas 1897”.

This inscription suggests that the image was purchased during the peak holiday period, a time when visitors thronged to Victoria’s Aboriginal missions and reserves. Like today’s tourists they sought respite in nature, but the perceived primitivism of Aboriginal people, combined with the fact that they could be seen living like Europeans on the missions, also attracted tourists in large groups.

Coranderrk Aboriginal Reserve near Healesville, where Barak lived from the early 1860s until his death in 1903, has been noted as a show place for Aboriginal culture. Along with woven baskets and boomerangs, Barak’s works on paper were purchased by visitors. As a diplomat he made the most of these circumstances to communicate across cultures.

It was not uncommon for visiting anthropologists and researchers to take a tour of Victoria’s Aboriginal missions. Many of these researchers came from Europe, visiting Australia on collecting tours which resulted in the assemblages of Aboriginal material culture now residing in museums the world over.

Museums in Switzerland and Germany hold the bulk of Barak’s overseas artworks. The Ethnographical Museum Herrnhut, Germany, for example, contends that missionaries “have made a significant contribution to the preservation and dissemination of knowledge about Indigenous peoples” through their observations, collecting of Aboriginal material culture and written records. Herrnhut, a small town east of Dresden, is the only place outside Australia where Barak’s artwork is currently on public display.

Barak’s work is a small but significant part of Aboriginal art in overseas museums. In Australia his works are held by state galleries, museums and libraries, as well as in private collections. It is thought only two of Barak’s 52 paintings are held by Indigenous-run organisations.

Though the Wurundjeri Council’s target was not reached, the donations gathered represent strong support for the idea of Barak’s work returning to Wurundjeri country. The A$45,337 raised will be used in the future to bring other cultural objects home.

Barak’s work has been seen in Switzerland and Germany, but Melbourne is where he is most known and loved. Perhaps the buyer of Ceremony will seek to share the work publicly with the city that continues to admire him most?