The Department for Education has been scrambling to end the crisis over allegations of extremism at Muslim schools in Birmingham (the so-called Trojan Horse affair). Among all the ideas floated, one, the “Louisiana option” of a full-scale government takeover of the schools in question, has started to arouse serious interest.

While hardly a simple solution, New Orleans’s radical attempt to turn around its failing school district has understandable appeal at such a fraught moment – and it’s a natural test case for officials in Birmingham and Westminster to use.

Segregation

In the 1840s, the City of New Orleans founded the first major urban public school system in the American South. But in a city made up of waves of multilingual immigrants, enslaved Africans, and free people of colour, reaching consensus on the purposes and structure of a public education system has never been easy.

The racially segregated public school system of the Plessy era came to a close after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, and the forced desegregation of New Orleans Public Schools took place in 1960. The school system became nearly all poor. Most middle class and non-white students either left for private schools or moved to nearby suburbs.

Intended primarily for the poor, Now Orleans’s public schools were chronically underfunded, suffered from poor results, and were frequently mismanaged. While generations of educators, both black and white, served admirably in difficult conditions, the schools still struggled.

Bankruptcy

After the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, student test data was made public annually, and showed just how far behind New Orleans’ students were compared with their peers across the state. And while academic achievement improved steadily in the years leading up to Hurricane Katrina, state policymakers viewed the school district and its predominantly African American students and teachers as a thorn in the side of the powerful economy of this historic city.

A month after Katrina, Louisiana Board of Elementary and Secondary Education member Leslie Jacobs stated in a radio interview that the district “was academically bankrupt, it was financially bankrupt, and it was operationally bankrupt … the central office ability to support schools was not there. So pre-Katrina, one could argue that Orleans public schools could vie for being one of the worst districts in the nation.”

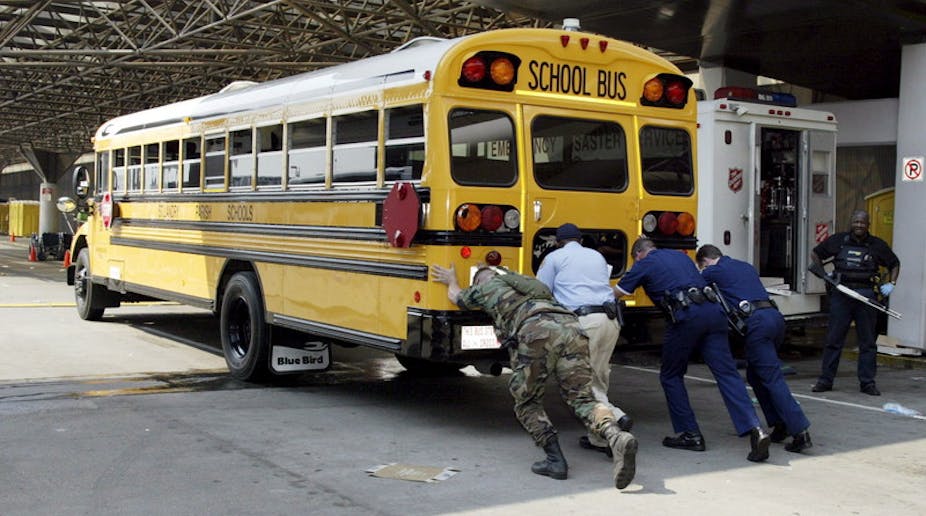

Following suit, on November 31 2005, three months after the hurricane and with most residents still not able to return home, the state removed nearly all of the schools from the locally elected school board and placed them under the control of the state-run Recovery School District.

This was achieved by adding a clause to a 2003 state takeover bill that allowed to state to define a “district in academic crisis” as any local school district with more than half of the schools deemed as failing based on student test scores. This meant any school performing below the state average (rather than simply a school with inadequate annual growth) could be taken over.

In turn, this allowed the transfer of nearly all local schools to state control and, crucially, to the dismissal of nearly 7,000 school district employees, who could not be paid by a district that now only received funds for the few remaining schools under its control. Due to the extreme displacement of the city’s population, there was little effective opposition to the move.

Mixed bag

To date, 79 of New Orleans’ 85 public schools (93%) are charter schools. The largest group (59 schools) are charters overseen by the state-run Recovery School District, with some schools run by the local school board and a few by the state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education. Ten non-profit charter management organisations run 42 of the RSD charters, with the remainder each governed by its own non-profit board.

Test scores have continued to rise, as they had been doing prior to Hurricane Katrina, but academic performance is still below average for Louisiana students. With the dismissal of many pre-storm teachers, and a rapid expansion in the numbers of young, alternatively certified teachers, the teaching force has become increasingly inexperienced.

A 2009 RAND survey found that parents tended to be satisfied with their schools, and have enjoyed greater school choice in the nearly all-charter system. The pro-market Fordham Institute named New Orleans the best US city for school reform in 2010 and both the federal Department of Education and private funders have heaped praise (and money) on the reforms.

As other cities have eyed the New Orleans reform, powerful local reform support organisation New Schools for New Orleans has published a Guide for Cities interested in implementing New Orleans-style reforms.

However, there have also been persistent criticisms of inequitable service for students with special needs and stringent discipline policies that push out challenging students. Critics have also raised legitimate concerns about the lack of local community participation and racially-targeted school closures. In January 2014, the teachers dismissed after the storm won in state court, setting the stage for possibly crippling back payments.

Nearly ten years into the reform, it seems clear that these decisions will ultimately help raise student achievement from its admittedly very low baseline. Mass conversion to charter schools, heavy reliance on inexperienced teachers, and a lack of centralised control have allowed the state to easily support the expansion of higher-performing schools and shut down lower-performing ones. It therefore comes as no surprise than citywide averages are up, and this is worth applauding.

But some of the policies that have made the past ten years of growth possible might also make it more difficult for New Orleans’s schools to be excellent, rather than just acceptable or mediocre. Until the city can re-establish school and community linkages, keep experienced educators in classrooms, and sufficiently educate the hardest-to-serve youngsters, we will not know if we have seen temporary gains or truly sustainable reforms.