In 2013, when Graham C Boettcher, chief curator at the Birmingham Museum of Art, first conceptualized a small exhibit examining the visual representation of race in American art, he couldn’t have anticipated the present political moment.

From events in Ferguson and Baltimore to the senseless murder of nine innocent people at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, America finds itself at another crossroads in race relations because of the harrowing effects of systemic racism.

When I was asked to co-curate this exhibition last year, I emphasized that race – specifically, “blackness” – has been constructed and visually represented from the perspectives of both blacks and whites.

Historically, whites have perceived and depicted African Americans as “different,” “picturesque” and, sometimes, “threatening.”

But African Americans have pushed back. They’ve resisted the ways whites often mythologized or satirized blackness, and have presented counter images: works of art that depict or comment on how we visualize our culture and ourselves.

The exhibit Black Like Who?, comprising works from the Birmingham Museum of Art’s permanent collection and private collectors, considers how political, cultural and aesthetic interests influence the artistic representations of black people and black culture at particular historical moments. The exhibit also takes into account the motives and beliefs of the artists, both black and white.

The show doesn’t claim to be an exhaustive examination of depictions of blackness in American art, but it does illuminate areas of American visual culture where blackness has been prominently defined.

There are five distinct sections:

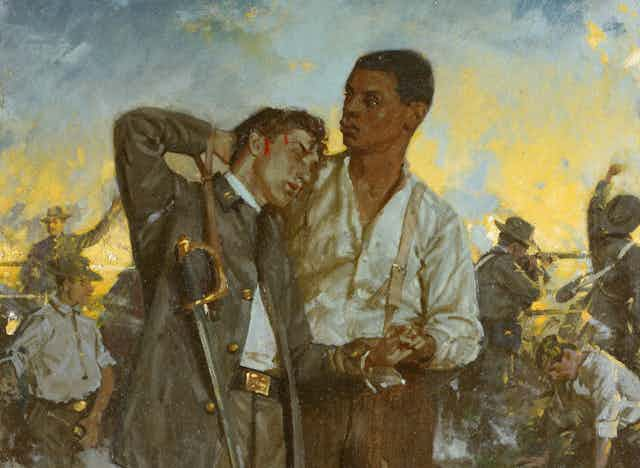

Old Times There Are Not Forgotten: Historical Representations of Race in the South and Beyond examines why and how artists depicted African Americans, from the Civil War to the Great Depression.

Black Like Me: African American Portraits looks at how white artists depicted black subjects in 20th-century American portraiture.

Brown Skin Ladies: Picturing the Black Woman illustrates how American artists, both male and female, represent African American women.

Body and Soul: Rhythmic Representations presents depictions of black musicians, and looks at how black artists use music as a painterly technique.

From Mammy and Mose to Madison Avenue: Advertising and the Black Image examines how black people and black culture are represented in commercial culture.

Altogether, Black Like Who? presents 28 works by 19 artists to show just how fundamental iterations of race are to the American experience.

For example, the section “From Mammy and Mose to Madison Avenue” exhibits photographs by Sheila Pree Bright, Hank Willis Thomas and David Levinthal.

Pree Bright’s work, from her Plastic Bodies series, blends imagery of Mattel’s Barbie doll with photographs of real black women. Her images show how the biases of white beauty standards distort understandings of race and natural beauty.

Both Levinthal’s and Thomas’ works contemplate how the stereotypes of Aunt Jemima and Rastus (the Cream of Wheat chef) inform American conceptualizations of the family breakfast. Levinthal’s photograph of Cooky, a popular cookie jar produced in the 1940s by Pearl China of East Liverpool, Ohio, critiques the prevalence of racist memorabilia in American kitchens – a domestic space that produced the most well-known racist imagery of black men and women.

Contemplating this idea through the black male body, Thomas photographs boxing great Joe Frazier dressed as the blonde Blue Bonnet margarine mascot to make a comment about the roles black men occupy in American advertising.

Together, these artists remind viewers of the ways racism is reflected in our commercial products. Racist understandings of black domestic workers have led to iconic caricatures like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, while beauty ideals that exclude entire groups of black women are represented in Barbie dolls.

The section Brown Skin Ladies juxtaposes works by Elizabeth Catlett, Henry Bannarn, Frank Hartley Anderson and Arthur Stewart to show how various American artists have challenged common depictions of black women. There’s a particular focus on how Bannarn, Anderson and Stewart – artists who are not black and female – navigate both stereotypes and controversial subject matter when presenting black women in their work.

Catlett, who has four works in the section, dedicated her career to accurately depicting black and Mexican women. Her sculpture Seated Figure celebrates the power, beauty and fortitude of black women: the figure sits tall, her head raised, back straight and feet planted firmly before her.

And visitors will certainly connect current events to Catlett’s 1970 lithograph The Torture of Mothers, where the artist visualizes the agony of a mother who has lost her son to police brutality. One hundred years after Catlett’s birth, her work endures as vital social commentary.

The hope is that the exhibit sufficiently engages both historical and contemporary works to show that for three centuries, American artists have been conducting a rather in-depth and complicated conversation about race. Perhaps the exhibition can also spark a conversation among visitors, who will see how past and present works of art have very real connections to recent racial tragedies, and the racial turmoil that continues to plague the American psyche.

Black Like Who? will run from July 11 2015 to November 1 2015 at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Birmingham, Alabama.