Iraq has a long and rich heritage, home for thousands of years to mighty empires – Assyria and Babylon, the Abbasid caliphate – that ruled the region once known as Mesopotamia, widely held as the cradle of western civilisation and as a major centre of classical Islam. The region is thick with history, and historical artefacts.

But when in June the extremist Sunni group ISIS took over swathes of northern Iraq, within a day or two of taking Mosul the group issued edicts which included orders to destroy Shiite graves and shrines and other ancient relics – orders which appear to have been carried out, with six sites destroyed. Rumour and fears over the possible fate of the region’s even more ancient cultural heritage under this heavy-handed new regime have filled the gap since.

And there is much to lose. In the desert 100km southwest of Mosul lies Hatra, an Arab city of the Roman period rather like its more famous sisters Palmyra, Petra and Baalbeck. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site with fabulous stone temples and statues (the originals now mostly in the Iraq Museum).

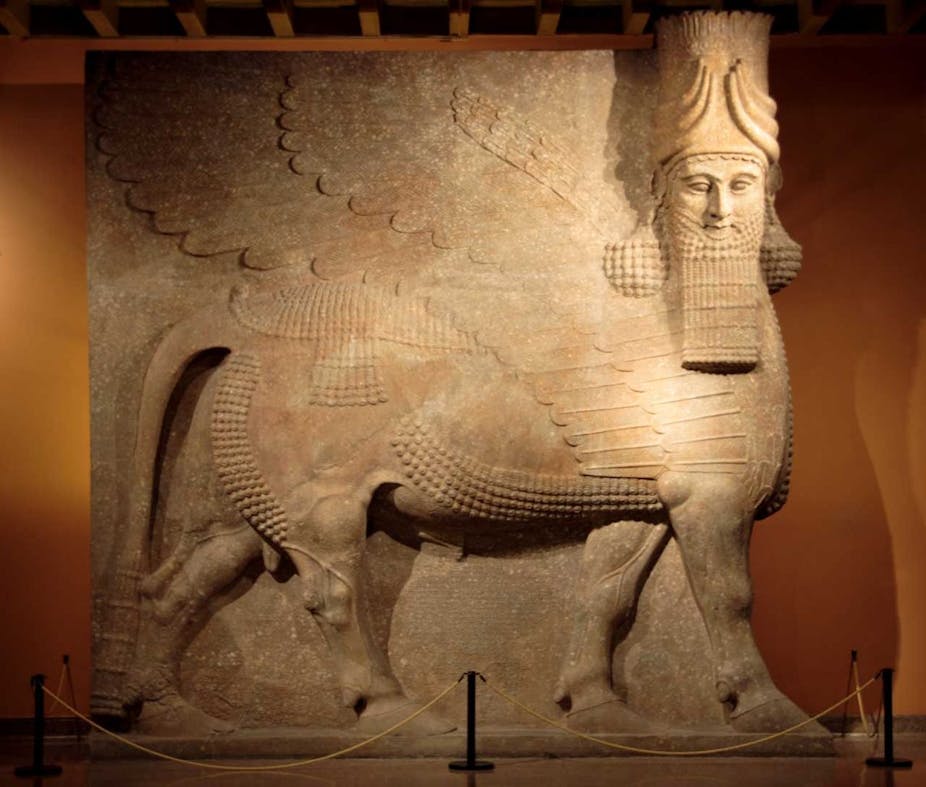

Mosul was heartland of the Assyrian Empire, which ruled the Middle East in the first millennium BC. Huge ruin mounds of ancient cities such as Ashur, Nimrud, and Nineveh follow the course of the Tigris river from Qalaat Sherqat up to Mosul and beyond. Since the mid-19th century its palaces and temples have furnished museums worldwide with monumental stone carvings of winged bulls and lions, and scenes of military conquest. Tens of thousands of cuneiform clay tablets, the majority now in the British Museum in London or the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, provide unparallelled insight into the workings of empire nearly 3,000 years ago.

The region is still dense with churches and monasteries from its time as a centre of Christian learning in the first millennium AD, which house important manuscript libraries as well as some of the last speakers of Aramaic, the language spoken by Jesus and the disciples. Although the last remaining Jewish inhabitants left the region in the 1950s, the Jewish community had first settled there as deportees from Assyria in the 8th century BC.

Mosul remained important during the Islamic period too. It was a centre of resistance against the crusaders – Saladin ruled from here – and home to eminent poets, scientists and men of letters. Many medieval buildings, both secular and sacred, survive to this day.

But what do we know about these developments, what can we expect, and can and should the rest of the world do about it?

Shifting sands

It is almost impossible to get verifiable news out of Mosul at the moment. The province goes for long periods without electricity or suffers communications blackouts. It is difficult to get through to colleagues by phone or by email. ISIS itself, however, is very adept at exploiting social media. The internet is filled with claims and counterclaims which makes it almost impossible to document reliably what is really happening. However, websites such as Conflict Antiquities and Gates of Nineveh are both keeping track as best they can.

The Association for the Protection of Syrian Archaeology has for three years documented the looting and destruction of cultural heritage in the occupied regions Iraq’s western neighbour, including a few isolated examples of iconoclastic smashing of ancient Assyrian statuary. It has been reported that sales of looted antiquities have helped to fund ISIS in Syria although, again, hard facts are hard to come by.

The understandable concern is that similar events will unfold in northern Iraq, although there is no evidence of it yet. While the experience in Syria suggests it is very likely, the historical evidence from within Iraq during the 1990s and 2000s reveals a different picture. During that time there were isolated instances of thefts from Assyrian archaeological sites for sale on the world market. Thanks to thorough archaeological documentation, however, it was possible to identify and repatriate stolen objects. Likewise, in the current situation, documented artefacts from museums and archaeological sites could all be potentially identified and recoverable if they were looted and smuggled out of the country.

But objects dug from as yet unexcavated sites are much harder to provenance. The tragedy is that however many thousands of artefacts are found attractive and durable enough for sale to make the pillaging worthwhile, many many more – and all of their archaeological context – will have been irreversibly destroyed in the process. The remoteness of desert sites in southern Iraq meant it was relatively straightforward to dig for Sumerian and Babylonian antiquities in the 1990s and 2000s. However, the Assyrian sites of northern Iraq have remained relatively untouched, so far.

Protect the past for the future

But 2014 is not 1991 or 2003, and ultimately it is impossible to predict what will happen. International treaties such the 1970 UNESCO convention against the illicit sale of cultural property,supported by national legislation, have drastically curtailed worldwide sales of Iraqi antiquities in the past ten years. But this has also driven the market underground, from where it is even harder to track stolen artefacts.

Why should we care about the fate of a few ancient statues and buildings? Is it not a first world indulgence to worry about preserving culture while people suffer and die? On the contrary, culture and people are inseparable: it is individuals and communities who create culture, culture that brings people together in meaningful, creative and constructive ways. Culture is the glue that holds societies together. It is a fundamental part of being human, living together.

We all have a duty to protect and celebrate Iraq’s multi-faceted cultural heritage, now and for future generations. It matters deeply to many Iraqis – and to many of the rest of us – and its fate cannot be separated from the human tragedy that is currently unfolding.