In 2012 Fremantle Arts Centre Press published The House of Fiction, a memoir by Susan Swingler. Last night the ABC’s Australian Story followed up with a program on Swingler and her book. Why all this interest in a memoir by an unknown woman?

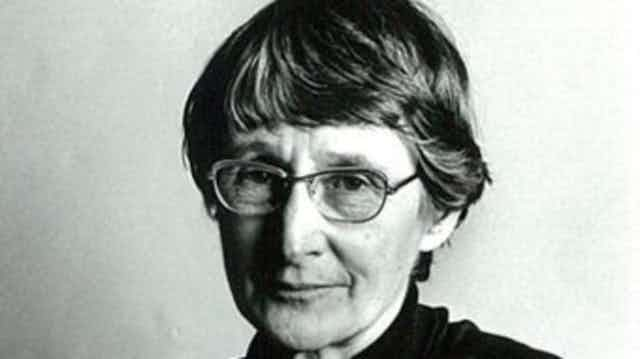

Swingler had been born Susan Jolley; her father Leonard later married one of Australia’s best known novelists, Elizabeth Jolley. Born Monica Elizabeth Knight in England in 1923, Jolley lived and worked in Western Australia until her death in 2007. To readers of Australian literature, she needs little introduction: her novels, including Mr Scobie’s Riddle (1983), Milk and Honey (1984), and The Well (1986), won all the major Australian literary awards and several international prizes.

Some of what Swingler revealed in The House of Fiction was already known before the book appeared.

Elizabeth Jolley had told an interviewer that her first child had been born before her marriage. Brian Dibble’s 2008 biography, Doing Life, filled in many details. Elizabeth and Leonard met while he was ill in hospital in 1940; he married Joyce Hancock in 1942 but later began a relationship with Elizabeth. Susan and her half-sister Sarah were born five weeks apart in 1946.

But Swingler’s book contained new information about a long-standing deception of Leonard’s family.

They were not told about his divorce from Joyce and led to believe that she and Susan had gone to Australia with him when he was appointed librarian at the University of Western Australia.

The House of Fiction includes copies of a letter supposedly from “Sue” in Perth to her “Dear Grandad” in England. Written in a style appropriate to a teenager, the letter is clearly in Elizabeth’s distinctive handwriting, if a little disguised. Many other letters to the family, supposedly from Joyce, were also written by Elizabeth.

When Susan confronted her mother after learning of this deception in 1967, Joyce claimed Elizabeth had told her Sarah’s father was a doctor at the hospital where she was nursing. In Jolley’s semi-autobiographical trilogy centred on nurse Vera Wright, the same claim is made by Vera when she is pregnant.

After I reviewed the first volume of the trilogy, My Father’s Moon, a colleague told me I was brave to refer to it as “semi-autobiographical”. Publication of Dibble’s biography and Swingler’s memoir have, however, revealed many parallels between Jolley’s life and fiction, especially in her later novels. Tellingly, Vera is an innocent-seeming manipulator who gets revenge on fellow nurses by leaving them letters supposedly from the Matron.

ABC pre-publicity for the Australian Story program included copies of two of the love letters, now in the Mitchell Library, sent between Leonard and Elizabeth while he was still married to Joyce. Reading some of these in 2008 had shown Swingler how strong their love had been. Yet such mutual heterosexual passion is rarely depicted in Jolley’s fiction. Instead she wrote about incest, lesbian yearnings and sexual triangles, her quirky humour not always disguising the human damage involved.

Launching Jolley’s novel Milk and Honey in 1984, fellow novelist Thea Astley offended Jolley by proclaiming that she was “sick” and suffering from what in a male would be called a permanent erection. Critics later remarked on the difference between Jolley’s self-presentation as a badly-dressed, meek and mild grandmother and the contents of her fiction. In an afterword to Swingler’s book, critic Andrew Riemer refers to this as “camouflage”, a deliberate strategy to separate author and fiction.

In 1988 Helen Daniel published a collection of essays called Liars: Australian New Novelists. Jolley was the only woman among the eight writers discussed. After struggling for years to get published, she came into her own during the 1980s. Literature was no longer being censored, realism no longer the only fictional mode. Secrets and lies were in vogue. As we now know, they had been part of Jolley’s life for much longer.

Does this matter? I don’t think bad behaviour should affect one’s reading of a novelist’s work. And in this case we know nothing about Jolley’s reasons for helping to deceive Leonard’s family.

Learning more about her life does, however, give us new insight into her novels, with their repeated character types and preoccupations, revealing just how intertwined her life and fiction were.