Remembrance Day commemorates the end of the First World War on Nov. 11, 1918, and the poppy is the abiding symbol of Remembrance Day in Great Britain and the Commonwealth countries, including Canada.

The poppy has been associated with war remembrance in a variety of ways. But as many who attended elementary school in Canada may remember, the poppy’s iconic popularity is often attributed to the poem by Canadian physician and poet, John McCrae, “In Flanders Fields.”

I would like to submit for consideration a different poem as a more suitable and ultimately more resonant poem to guide our reflections this Remembrance Day: Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est.”

‘In Flanders Fields’

“In Flanders Fields” begins with a haunting evocation of poppies growing between marked graves of the war dead in Belgium, a description delivered by those very dead. In Canada and beyond, the poem has become a mainstream literary representation of all the wars and casualties remembered on Remembrance Day.

I have always found McCrae’s poem unsuitable to commemorate the war or Remembrance Day. Its appeal may be attributed to its melancholy focus on the makeshift graves of the dead and its earnest attempt to create an empathetic connection with the reader:

“ … Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders Fields.”

What follows from this poignant memory of being alive, however, is a command to “Take up our quarrel with the foe,” and a warning that these dead will not sleep until we, the readers, avenge their death on the battlefield.

The directive to continue the war until the foe is vanquished is antithetical to the spirit of Remembrance Day as I conceive of it. It’s similarly antithetical to the finest British poetry of the First World War, including that penned by Wilfrid Owen.

Poetry & shell-shock

Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” has an unambiguous anti-war message, and it works skillfully to immerse the reader in a subsuming, visceral representation of the lived experience of the frontline soldier.

Unlike McCrae, Owen never identifies the “foe” as the German soldiers in their trenches, but rather directs his ire at those at the home front who perpetuate, or simply believe in, the propaganda glorifying the war. The same can be said for Owen’s compatriot writer and friend, Siegfried Sassoon.

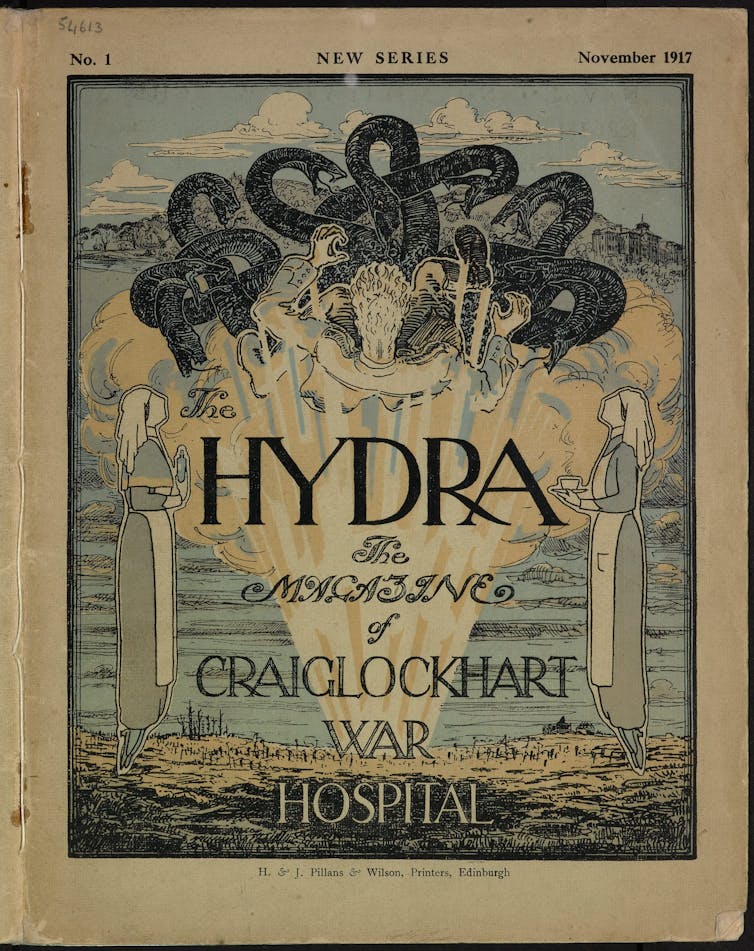

Both Sassoon and Owen — who met in 1916 while they were both recovering from shell shock at the Craiglockhart Medical Hospital in Edinburgh — felt that young men like themselves had been betrayed as objects of hero worship by their country.

The title “Dulce et Decorum Est,” is from Horace’s epigrammatic line “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” (it is sweet and proper to die for one’s country), which is still inscribed on many war memorials. At the end, the poem excoriates this motto as “the old Lie.”

Angry rebuke

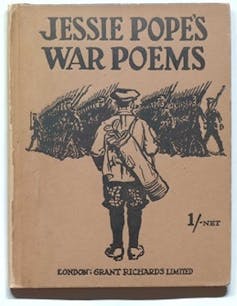

Owen’s poem is an angry rebuke to jingoistic poets of his time, such as Jessie Pope, whose wartime poems aimed to rally and entice new recruits and lift up “war girls.”

In 28 lines, Owen strives to convey, as accurately and brutally as possible, the daily horror experienced by front-line soldiers. At once, his poem is conventional — adhering to iambic pentameter and a strict rhyme scheme — and highly innovative. His language is designed to provoke emotion in the reader, as we see from the opening four lines:

“Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.”

The similes comparing the soldiers to “beggars” and “hags” are striking, but so too is the use of the first-person plural to describe the soldiers.

The words “sludge” and “trudge” stand out in this stanza for being distinctly vulgar in their context, while exemplifying the onomatopoeic language that Owen uses to help us experience the soldiers’ fatigue. The elongated vowel sound — “uh” — perfectly mimics the weary drag of the soldiers’ feet as they “trudge” through the muck.

The lethargic pace of the first lines swiftly accelerates when the soldiers are subjected to a gas attack:

“Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! — An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time.”

The reader must accelerate their reading pace and perhaps even experience a quickening heart rate alongside the soldiers.

‘I saw him drowning’

The rest of the poem is focused on the lone man who didn’t secure his helmet in time, and who the narrator is forced to watch entering his death throes:

“But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.”

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.“

These lines are thick with active verbs; the suffix "ing” dominates the description of the gas attack, and the lines that follow conclude the poem:

“If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face …

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory …”

No peace for the dying

In these final twelve lines of the poem the “we” shifts to “you,” when Owen attacks the notion of glorifying war without any direct experience. The “you” may be both a direct reference to Pope and the kind of audience she sought to capture: Owen originally dedicated the poem in his original manuscript “To Jessie Pope, etc.,” and then in another version “To a Certain Poetess.”

The biggest shock produced by “Dulce et Decorum Est,” though, is when we realize the victim is still alive at the poem’s end — or, still dying.

Owen does not allow this man to slip off into the ruminative afterlife experienced by McCrae’s war dead. He keeps his victim suspended in the act of dying as a way of preserving the poem’s fraught message. There is no peace for this man, until “you,” the reader, reject the “old Lie” and fight to end the war.

Owen was killed in action a week before the war’s end, on Nov. 4, 1918.

Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” is a meticulously crafted poem of shock and haunting. It might do us good to feel such haunting, such shock, every Nov. 11.