Media-fuelled moral panics can increase the lawbreaking behaviour of targeted groups. This phenomenon was originally thought to arise through further isolation of these groups. But in the age of social media and online self-promotion, where lawbreakers can upload footage of their illicit exploits for kudos, being the subject of a moral panic may be a source of pride and an inducement to offend.

As American criminologist Ray Surette notes:

When the news media sensationalise crimes and make celebrities of criminals, people seeking notoriety imitate those crimes, sometimes posting movies of them for all to watch.

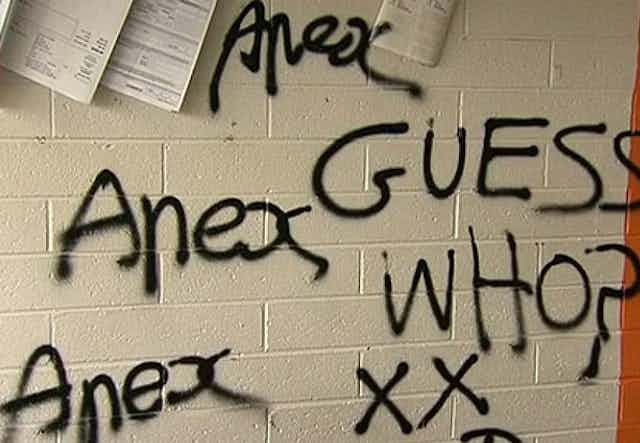

This is seen clearly in the rise of Apex in Victoria. A loose collective of youths has come to be associated with a much-reported rise of carjackings and home invasions in the state.

When gangs become brands

Throughout 2016, Apex was the subject of intense media scrutiny in Victoria. Tabloid news articles regularly attributed the state’s rise in crime to the group. In several publications it seemed the term Apex became a catch-all for youth crime in Victoria.

However, Apex isn’t an organised crime gang. As both police officers and group members have noted, Apex is less a gang than a loose network of youths connected by social media. Websites like Tumblr represent a platform for Apex to co-ordinate activity and promote crimes that its members have committed.

While the tabloid media certainly didn’t create Apex, it has helped transform the group into a brand. Such sensationalised news coverage has fostered several crimes committed under the group’s name by individuals only loosely, if at all, connected with the collective.

Like the “scratchitti” tags etched into cars by individuals claiming to be Apex members, the name suggests affinity with a particular identity more than affiliation with a formal organisation. In this sense, Apex is now not so much a gang as a hashtag – a rallying cry or scapegoat for lawbreaking youths who otherwise have little connection with one another.

Describing Apex as “notorious” or “infamous” and sensationalising its members’ exploits acts as free publicity and a recruitment drive for the group.

Throughout 2016, as the tabloid media ramped up its coverage of the group, the number of individuals affiliated with Apex grew. It had fewer than 200 members at the beginning of 2016, but is now estimated to have grown to upwards of 400 members. Members attribute Apex’s growth to it becoming better known.

Performance crime and antisocial media

Apex primarily uses social media to coordinate activities, legal and illegal. But an increasing number of organised crime gangs and lawbreakers use these sites as platforms to promote their crimes.

Many of these acts are performance crimes staged for the camera and a social media audience. Such crimes are undertaken to build fame, reputation and notoriety.

Giving the individuals and groups who undertake these crimes additional media attention is, therefore, exactly what they want. Perpetrators commit such acts with the hope they will receive media coverage, which many tabloid publications eagerly provide.

One example of this social-media-facilitated phenomenon that has attracted significant media attention is Facebook pages dedicated to hosting footage of street fights and bare-knuckle brawls. These are “antisocial” media: video aggregators that host and sympathetically curate footage of criminalised acts.

As with Apex, sensationalised news reports on fight pages and other forms of antisocial media can increase the number of individuals connected with these groups. Many fight pages wear such reports like a badge of honour, and post screenshots of headlines they feature in to great applause from their followers.

This isn’t to say that news media shouldn’t report on performance crimes, antisocial media, or gangs with a social media presence. Nor is it to place the blame for these primarily at the media’s feet.

While social media and media-fuelled moral panic do play a part in the rise of these phenomena, each is the product of many social, economic, cultural and technological factors. Focusing on only one of these factors, rather than drawing the connections between them, will not help produce an accurate picture of these phenomena.

However, as Apex’s increased profile and membership demonstrates, giving such groups sustained media attention and sensationalising their crimes can have negative consequences.

It remains important that news media recognise their potential to amplify criminal behaviour through sensationalised reporting that eschews analysis in favour of graphically describing lawbreaking collectives. Sensationalised reports not only promote ineffective “lock ‘em up”-style criminal justice policies, but represent free promotion for individuals and groups in search of infamy and notoriety.