For the first time in Northern Ireland, women will be able to access abortions without having to travel to Great Britain as of April 1. This is the culmination of years of fighting for access to reproductive healthcare and follows similar changes in Ireland, where abortion became legally accessible in January 2019.

As heated debate raged across both Northern Ireland and Ireland in the lead up to these changes, the stories of women, who for various reasons, took the “abortion trail” across the Irish Sea became more widely shared. These are personal and often harrowing stories of being forced to travel to Great Britain to terminate a pregnancy.

Indeed, while it may not be widely known, women who did not want to be mothers in Ireland are also a consistent feature of Irish migration throughout the 19th century. Some took the short journey across the Irish Sea to Great Britain. Others, however, took their chances further afield responding to the promises of a fresh start in America.

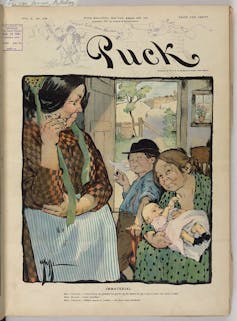

We have been researching these stories for our “Bad Bridget” project, a three-year study funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council named after the fact that Bridget was commonly used in 19th-century North America to refer to Irish women. From looking at criminal and deviant Irish women in Boston, New York and Toronto, we have uncovered many who made the extreme decision to emigrate while pregnant and often alone.

It is clear from our research that the stigma and shame attached to illegitimacy in Ireland, in both protestant and catholic communities, led girls and women to make this journey to the “new world” rather than be condemned and possibly ostracised at home. In 1877, for instance, Maggie Tate, an Irish Protestant, migrated to New York to “cover her shame”. She hoped that the father of her child would join her in the US to fulfil his promise to marry her.

Kate Sullivan, who was 18 when she travelled to New York, was “betrayed” by the son of a farmer for whom she worked in Ireland. He had allegedly “shipped her over [to New York], promising to follow on the next steamer”. He didn’t and she gave birth to their twins there.

Other women in similar situations gave up their children for adoption. While some relatives and friends would likely have been complicit in decisions to hide pregnancies by migrating across the Atlantic, others likely remained entirely ignorant. Unfortunately, many Irish women found that when they arrived in America, attitudes towards single mothers were no more positive than at home. For some women the experience of migrating while pregnant ended in tragedy.

Catherine O’Donnell ended up in court in Boston in 1889 for the suspected manslaughter of her baby, having allegedly “sought the shore of America to give birth to an illegitimate child, her lover [in Ireland] deserting her”. Her case reveals the issues experienced by many single mothers, both in the past and today, of having to support a child alone. Catherine initially paid for her baby’s board, but her financial difficulties were exacerbated when money from home ceased. She was refused assistance at charitable and religious institutions and, after wandering around for two days in a storm, seems to have left her infant on the shoreline at low water where the baby drowned.

Abroad and alone

Our research on Bad Bridget has also shown that many Irish female migrants became pregnant after their arrival to North America. This is undoubtedly related to the fact that many Irish women emigrated alone and at a young age, some as young as eight or nine. This was unlike their counterparts from continental Europe, who tended to travel in family groups.

But if many Irish migrants in large cities experienced a new found sexual freedom outside of parental and family control, this lack of supervision also meant a lack of support and assistance. The experience of Rosie Quinn who became pregnant while in New York in 1903 reveals the tragic consequences that could follow. Rosie was found guilty of throwing her nine-day-old daughter into a reservoir in Central Park and sentenced to life in prison. Her case generated considerable public support, with one woman writing to the governor of New York:

my heart is so burdened for that poor Irish girl (alone in a strange country deserted by family and friends) that I cannot rest.

Like Catherine O’Donnell, Rosie explained during her trial that she had sought and been refused charitable assistance. She had gone to Central Park intending to drown herself and the baby, she claimed, but while contemplating suicide the baby had slipped from her arms. She recalled that she “got scared and ran away”. Servants at the hotel where Rosie had worked on Fifth Avenue appealed to patrons to help appeal her case and she was pardoned in December 1904.

These examples are only some of the wide variety of stories and experiences of unmarried Irish mothers in North America. In many situations, pregnancies outside marriage will have turned out well; women will have managed on their own, married or used support networks. But for others, experiences of emigration ended badly. Historical discussion of emigration often ignores the female experience.

Understanding the myriad migration stories in the past will give greater insight and understanding into the pressures and demands of migration today, especially relating to women migrants. Such stories also complicate rose-tinted views about economically, socially and politically successful Irish migrants who contributed to their new home countries. An awareness of the variety of pressures and stresses that led to a decision to emigrate, and an understanding that not all migrant experiences in the past were positive, can encourage a more empathetic consideration of migrants and migration today.