I saw two very different shows at the Edinburgh Fringe last week, two shows that dealt with the subject of how men and women talk about each other, in very different formats and with very different levels of success. But notably, each play made a similar stylistic choice of switching roles – women performed male voices and men performed female voices, casting an interesting spin on the proceedings.

Locker Room Talk by Gary McNair raised questions about how normalised notions of sexism and misogyny are in all-male situations, while the Royal Court Theatre’s Manwatching, written anonymously, focused on female sexual desires and fantasies about men.

Inspired by the US president’s now infamous “grab them by the pussy” remark – which he dismissed as “locker room banter”, playwright Gary McNair set out to investigate what men really say about women when they’re not around to listen in on the conversations.

He recorded hundreds of men, discussing how they talk about women including what their thoughts are on issues such as equality, sexism and feminism. Directed by Orla O’Loughlin, the conversations were expertly performed by four actresses channelling the voices of men of various nationalities, ages and socio-economic backgrounds.

During the post-performance discussion, McNair explained his reasons for having women perform the conversations: to return agency to the subjects of the conversations – and because women were the ones not supposed to hear these conversations. The effect of the gender reversal was to focus on the words rather than the speaker.

Words are the crux of the problem of everyday sexism expressed through the voices in this performance.

Rather than dismissing this kind of talk as something only expressed by the likes of Trump – in other words, as separate, rare incidences – the performance pointed to the core of this matter: that the US president’s words are a symptom of a much larger issue of systemic sexism and misogyny.

The performance also raised some interesting points about the significance of humour. As one of the voices in the performance said:

It’s more about the tone when you say something. Like when he [Trump] said it, it sounded quite rapey and seedy, but when we say it, everybody knows it’s a joke.

So humour in these conversations becomes an excuse for sexist and misogynist language – dismissed as harmless because it was meant as a joke.

Men laughing at women laughing at men

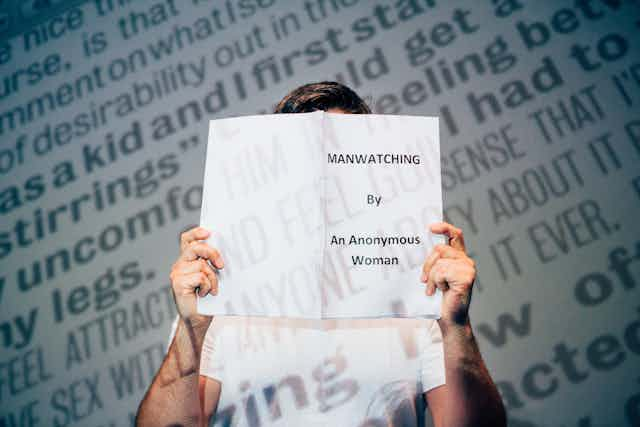

The other performance, Manwatching, offered an insight into the sexual desires and fantasies of an anonymous heterosexual woman. Directed by the Royal Court Theatre’s Lucy Morrison, each night a different male comedian performed the script without any previous knowledge of the content.

On the night in question, comedian Darren Harriott started giggling as soon as he opened the envelope with the script, prompting laughter from the crowd. And here we encounter the main problem: already the audience was laughing with the male comedian at the female author. The problem is then both stylistic and gendered.

In an interview in The Guardian in January this year, the playwright explained that her choice to remain anonymous allowed any woman to take ownership of what was being said. She added that the intention was to objectify the male comedian speaking her words and subvert the male gaze.

The manuscript did in fact give an interesting insight into heterosexual female desire and raised important issues such as how female masturbation is structured as shameful and how problematic it can be to deal with unwanted sexual attention from an ex-boyfriend.

Getting it wrong

The play opens with the author detailing what she finds attractive in a man, evaluating all physical attributes. The fact that a man reads out what a woman would find attractive in him could then potentially work as a very interesting reversal of the male gaze. This, however, was not the situation we were presented with in this performance.

Instead, the manuscript was filtered through a male comedian laughing at the words expressed by an anonymous woman. Female sexuality was ridiculed rather than legitimised. And rather than giving voice to a woman’s desire and fantasies, any notion of female agency disappeared while the audience laughed along with the comedian.

To me it seems fundamentally problematic for a play that aims to reverse traditional gendered notions of objectification and reclaim female sexual desire to have a man speak for the woman. Interestingly, Guardian interviewer Brian Logan saw the play quite differently:

Add the rich pleasure of watching a male performer negotiate the text moment by moment – even when it starts joking at their expense – and you have an intriguing hour in the theatre, one that reclaims a small patch of male privilege and deviously upends the male gaze.

Troubled by this format, I struggled to focus on the words expressed in Manwatching, which seemed a shame, and in stark contrast to the significance the language bore in Locker Room Talk.

The words we say every day are so very important. They are neither harmless nor insignificant, and there is no such thing as “just a joke”, especially when it comes to sexism and misogyny. Sadly we hardly often notice, or are forced to excuse them because they are dismissed as “harmless banter”. The depressing thing is, it is anything but.