We seem to have always believed, dreamed and played with the idea of floating, somehow unsupported by very much. Utopian socialist architectural movements in Soviet Russia imagined vast levitating cities and housing blocks in direct contrast to their grounded, capitalist counterparts. In contrast, Jonathan Swift imagined the lodestone powered flying city of Laputa, directed and designed to assert power over earthly populations.

The floating, light and ethereal body is also a figure common to the spiritual (stories of ascension can be found in most religions) but also popular imagination – such as the ubiquitous superhero figures and earlier representations of science fiction. Dr Strange is lifted by his levitation cloak, Aladdin by his magic carpet and Superman hovers above and speaks down to terrestrial governments and their populations, performing sovereign acts outside of the rule of law and order.

Levitators in literature, cinema and popular culture commonly express yearnings for escape – in the 1985 classic film Brazil, Buttle (Jonathan Pryce) daydreams of winged flight to escape his administrative hell, for example.

Perhaps it seems natural to see levitation as a superfluity and less deserving of more weightier topics (note how we divide issues by senses of height and weight). But as I suggest in my new book, levitation deserves much greater scrutiny as an important note in our scientific, cultural and spiritual imagination. More often than not, levitation tends to belie stark inequalities, various forms of violence (often upon women), and even oppression, sexualised exploitation and racism.

The fat witch

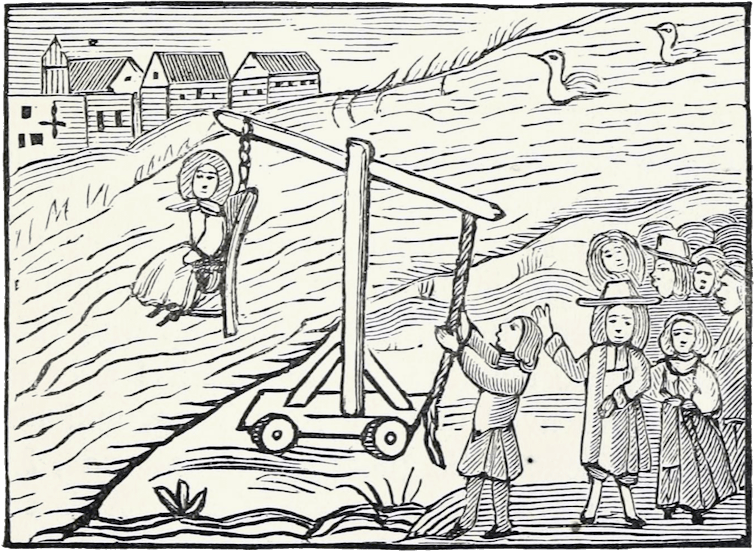

Female levitators are often maligned as ridiculous, dangerous characters, often by men. This is a very old trait, but was solidified and given shape by the influential Jesuit theologian Martin Delrio, who published Disquisitiones magicae (Magical Investigations) in 1599–1600. His book popularised the idea that demon spirits could posses or inhabit a female human body. It also suggested how to identify and track them. For the witch-hunters and storytellers of early modern Europe, the levitating, flying witch was a figure of grotesque femininity, and often portrayed as fat.

In a way, the relationship between the levity of witches and weight is central. It was the idea that witches were corpulent that made the idea of their flight seem so uncanny, so wrong. And of course, trial by ordeal – whereby it was “tested” whether a woman was a witch – was completed not so much by assessing the weight of a potential witch but by their buoyancy: flotation proved guilt.

The collusion between ideas of levitation with femininity, weight and gendered suspicion and exploitation have continued. We find many tales of levitation in the stories and investigations of Victorian mediums, a popular figure of attraction in the homes and domestic settings of the metropolitan middle classes in the late 19th century. As well as contacting the spirit world and exuding mysterious substances, many mediums claimed to, and were believed to, possess the power to levitate things and sometimes themselves. Mediums were also an object of considerable scrutiny for philosophers, physicists, psychical investigators, and sceptics.

Floating mediums

Figures such as the famous Mrs Guppy and the Italian medium Eusapia Palladino stand out. Mrs Guppy ignited middle-class intrigue in the wake of a tale of her transportation and levitation from a friend’s home in Highgate to Lamb’s Conduit Street in Holborn on June 3 1871. Palladino, on the other hand, held many sittings – some of which were conducted under scientific observation and measurement – where she purportedly levitated various tables and objects, much to the amazement of audience members, who ranged from Marie Curie to the the racial criminologist Cesare Lombroso.

Guppy and Palladino became highly sexualised figures. Both were taunted and ridiculed for being fat. Many newspaper characterisations of Guppy’s flight played upon the size and weight of her body, repeating some of the tropes of fatness and supernatural flight associated with the witch we found above. Weight and lightness were a prime object for satire, making her levitation seem somehow more absurd, while hinting at her apparent low class, low morals and yearning for both sex and ascendance. Sex and flight are common pairs as Freud would try to make clear – he was also afraid of flying.

For women, levitation has tended to be viewed as an affliction, as a fraudulent power and diminishing of class or status, or as the supernatural puppetry of a male protagonist pulling the strings. Men hardly ever levitate in the same way, appearing to be far more wilful, assertive and domineering – or simply close to god, as the many religious tales of levitating saints attest.

Feminist reclamation

More recently, there have been efforts to try to reclaim the female levitator from an object of male desire, control or exploitation. Mid 20th-century surrealist friends Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington (who was expelled from a convent school for her rebellious behaviour: attempting to levitate was one of them) used magic and levitation in their works to unsettle the status quo. Their magical landscapes featured women in the position of scientists, explorers and magicians, floating things or themselves.

Female levitation has also been used to enliven some pithy social commentary. In The Kármán Line (2014), a short BAFTA nominated film by Oscar Sharp, Olivia Colman is ever so slowly lifted off the ground in a form of “magical social realism”. She eventually crosses the Kármán Line boundary – the line between earth and space where the atmosphere becomes too thin to support heavier than air flight. The film is a commentary on family detachment and figurative estrangement to the slow loss of a woman from the home. Her slow rise through the house and into the sky stretches and collapses conjugal, motherly, familial and terrestrial attachments. The film is incredibly sad, but is also a story of hope, of coming to terms with – and living on after – a drawn-out death.

These stories of levitation – and the parallel histories of human flight – are not as light as we might have thought. This history demonstrates that what often seems like an escape is usually more plainly an expression of oppression and powerlessness. But these stories need to be re-examined – and the female levitator potentially reclaimed.