With boots on the ground being costly politically, economically and diplomatically, it seems that week after week, drones are the most important front line weapon against Washington’s opponents in the War on Terror.

In my column recently I looked at the evolution of autonomous aircraft and their current status as the long arm of American foreign policy.

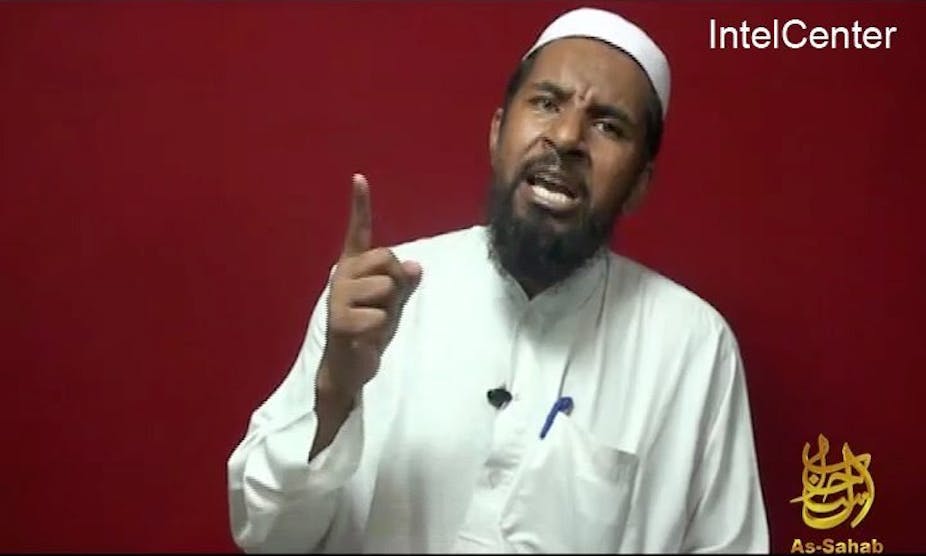

The strike carried out this week by a US drone on Libyan-born al-Qaeda depyty Abu Yahya al-Libi in northern Pakistan is a case in point. The action was, according to America’s Defense Secretary Leon Panetta “about our sovereignty”.

By that, Panetta means that popping a Hellfire missile into the mouth of a cave in Waziristan is a means of safe-guarding American interests back in Cleveland. Well, assuming you get the right guy and the act doesn’t alienate so many more locals that you create a never-ending stream of new recruits.

But is it fair enough if one country is flying a robot plane through the airspace of another country and using it to deliberately kill a citizen of a third state? The morality and legality of targeted killings I will leave to those more experienced in the laws of sovereignty and ethics. I would, though, like to know two things:

1) Who decides who is guilty enough to make it on to a death warrant for Obama to sign?

2) How many “number twos” can one organisation have? It seems that we’re always nailing another “al-Qaeda number two” or “trusted lieutenant”. That’s one flat organisational chart.

Warfare on the cheap

Aside from those questions it is worth examining the phenomenon of drones (or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) in terms of why they are used, and what bonuses and costs they have politically. For using drones as a weapon of choice against terrorist cells is at the same time a precision tool and a blunt instrument.

The big tactical attraction with the robot aircraft is, in football terms, their “hang time”. A Predator UAV can stay aloft for up to 24 hours. They don’t sleep, don’t eat, don’t get stressed out, can see in the dark and after that 24 hour stint they’ll be ready to do another shift straight as soon as the fuel tank is topped up. And if something goes wrong and they end up as a pile of debris scattered over an acre of Afghan hillside, nobody needs to send them home in a flag-draped coffin. At just $4 million a pop, Predators are huge value for money.

Given the nature of the terrain where America is hunting terrorists, drones are an easy solution compared to inserting troops and much more cost efficient than using conventional fighter-bomber aircraft. You can have a drone circling a patch of turf day and night, just waiting for a target of opportunity or a particular individual to pop their head up.

Then it’s up to the controllers back at base to give the nod and fire the missile and … BANG! Instant job opportunity for a new al-Qaeda number two.

Strategic killing

In strategic terms, drones are a good way of continuing a war while everybody can pretend it’s not happening. Having a few battalions of Marines sitting in Pakistan or Yemen would be politically difficult, both for America and the “host” country.

And it’s bad for the Marines too when they keep getting their legs blown off by IEDs whilst fruitlessly chasing shepherds around the mountainsides.

Drones mean that politicians can say, “We’ve brought the boys back home,” while still making sure there are some positive bad-guy killing stories in tomorrow’s Washington Post. President Obama has been a bigger user of drones than his predecessor for precisely this reason.

Collateral damage

But this robotic presence is still a presence. And it’s here we find the drawback of this arms-length warfare: drones kill people. Sometimes, not the right people either.

Naturally, figures vary, but drone strikes in Pakistan alone have been linked to up to 800 civilian deaths. Sadly that sort of figure is just a drop in the ocean considering the body counts that occur monthly in Afghanistan and Pakistan, but one has the sense that using a drone to carry out these sort of killings makes it all the more remote from our minds.

However this sort of collateral damage is not remote from the considerations of Pakistanis. The apparent impunity with which America operates its unmanned aircraft over their skies has incensed the government in Islamabad. Especially when Leon Panetta tells them to shut the hell up because this is all about American sovereignty. The Pakistanis also see the drone attacks as counterproductive, creating opposition and resentment that plays into the hands of the terrorist groups.

Kill the bad guy, save his family

We know that these criticisms of the drone campaign must have some grounds because even the CIA is getting squeamish.

This has seen the development of a “Lite n'Easy” model Hellfire missile – one with a smaller warhead. The idea is that firing one into the Hilux the bad guy is riding in won’t wipe out the whole of the wedding convoy he’s travelling with. Going to the trouble of inventing this solution is an indication that targeted killing from unmanned aircraft is considered a long-term plan.

Whatever the outcome of the American elections this year it’s a fairly safe bet that drones won’t be voted out. And as long as al-Qaeda keeps that sprawling hierarchy there will be plenty more targets for these graphically-named birds of prey to pursue.