Rock and roll has always been a great liberating force in our culture. For many it has provided the soundtrack for all manner of acts of political rebellion and personal liberation. This spirit is captured in many of the great classics of the genre: Anarchy in the UK, Like a Rolling Stone, I Can’t Get No (Satisfaction), Smells like Teen Spirit.

As Greil Marcus, the American music critic, has described the all-pervading rock ethos: “More than anything else, rock music has served as a relentless cry for freedom”.

Fellow music scribe Lester Bangs goes further, suggesting that the great rock bands provide us all with a permanent vision of “a better society”. But is this really the case?

Is this great popular form really the overwhelming force for good that we all imagine?

The idiom of rock

Another reading of the rock canon is to see it actually as an imposing – even authoritarian – idiom, a quality seen vividly in the titles of many rock classics. Let me explain.

Traditionally in linguistics, sentences can be divided into three basic types: statements (declaratives); questions (interrogatives); and commands (imperatives).

In the rock oeuvre, many an anthem has been constructed around the first of these structures:

-

I am an anarchist, I am an antichrist (Sex Pistols)

-

I can’t get no satisfaction (The Rolling Stones)

-

The boy looked at Johnny (The Libertines).

Other great songs have taken as their point of departure the posing of some potent and compelling question:

-

How does it feel (to be on your own)?(Bob Dylan)

-

Should I stay, or should I go? (The Clash)

-

How can we sleep when our beds are burning? (Midnight Oil)

But I want to suggest that it is actually the third of these types – the imperatives – that is actually the real lingua franca of the rock song, and thought of in this way gives a very different reading on rock’s basic messages.

Telling us what to do

Linguistically, the imperative is constructed by a single verb (eg. “Shout”), plus optionally various other elements: prepositions (“Shout to the top”); adverbs (“Shout it out loud”); other verbs (“Shout and deliver”).

While the other two forms – the statements and questions – are mainly about information (telling or asking about things), imperatives, by contrast, are about actions (telling one to do things).

The British linguist Norman Fairclough has picked up on this quality, describing the imperative as the language form most associated with “acts of power and domination”.

This is abundantly clear if we do a quick survey of imperative-based songs.

Take for instance, those with the verb “get” in these titles:

-

Get off of my cloud (The Rolling Stones)

-

Get off (The Dandy Warhols)

-

Get back (The Beatles)

-

Get back in line (The Kinks)

-

Get outta my way (Kylie Minogue).

Far from being about the promise of liberation and rebellion, these are songs about just being pushy.

The same is true for imperative songs about the conjugal act. Rock music has always been seen as a great aphrodisiac, but one wonders how much it really has served to advance the cause of sexual liberation.

The following titles betray a decidedly one-sided take on gender relations, not to mention a disconcerting interest only in one’s own gratification:

-

Call me (Blondie)

-

Relax me (The Groove)

-

Touch me (The Doors)

-

Start me up (The Rolling Stones)

-

Light my fire (The Doors)

-

Give it to me (Madonna)

-

Gimme more (Britney Spears).

And James Brown’s contribution to the genre – Get up (I feel like being a) sex machine – reads nowadays as just old-fashioned sexual harassment.

Now, I don’t want to suggest that all these “imperative” songs are just about the crude imposing of one’s will on others.

Civil imperatives

The Four Tops Reach out (I’ll be there) is a powerful expression of fidelity and love; and John Lennon’s Imagine, if it is a command at all, is about as poignant as one of these can be.

Other songs also manage to maintain a commendable degree of civility in the demands they place on others:

-

Please please me (The Beatles)

-

Baby please don’t go (ACDC)

-

Please don’t leave me (Pink)

-

Please, Please, Please, let me get what I want (The Smiths).

The rock and roll drill sergeant

But more often than not, the instruction is pretty blunt.

Consider the following single verb titles, which taken together end up sounding like the barking refrain of a testosterone-charged drill sergeant or overhyped gym trainer :

-

Wake up (Arcade Fire)

-

Get up, stand up (Bob Marley)

-

Jump (Van Halen)

-

Push (Matchbox 20)

-

Run, Run, Run (Velvet Underground)

-

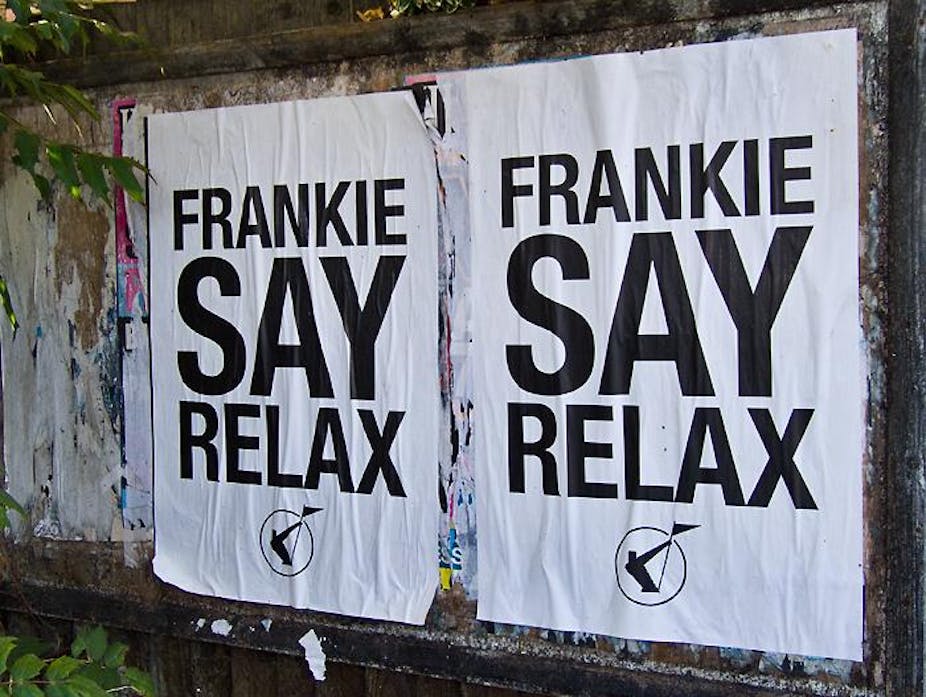

Relax (Frankie Goes to Hollywood)

-

Do it again (Steely Dan).

In these examples the instruction is at least clear.

Often though, the logic is difficult to follow. The Beatles, for example, over their long and distinguished career, were great dispensers of advice and instruction. I’m not sure though what sense we might make collectively of the following directives from their extensive catalogue:

- Drive my car

- Run for your life

- Carry that weight

- Dig it

- Let it be

- Act naturally

- Come together

- Get back

Don’t do it like this

Along with instructions about what one is required to do, a good number of songs are insistent in the same measure about what we should all avoid doing. Some of this advice, admittedly, is benign enough:

-

Don’t worry, be happy (Bobby McFerrin)

-

Don’t be cruel (Elvis Presley).

But many songs are just downright interfering. The following titles should all be seen as nothing but a serious cramping of the teenage style:

-

Billy, don’t be a hero (Paper Lace)

-

Don’t pay the ferryman (Chris de Burgh)

-

Don’t talk to strangers (Rick Springfield).

Watch how you walk

Not only is there advice about habits of talk, but also about the way one should “walk”. Indeed the rock canon abounds with instructions about how we should all comport ourselves:

-

Walk like a man (The Four Seasons)

-

Walk this way (Run DMC)

-

Walk don’t run (The Ventures)

-

Walk and don’t look back (Mick Jagger and Peter Tosh)

-

Walk on by(Dionne Warwick)

-

Walk on the wild side (Lou Reed).

This theme of preferred pedestrian styles also provides what is arguably the silliest directive ever issued in a rock song: Walk like an Egyptian (The Bangles).

Stuck on ‘it’

The relentless issuing of instructions is seen no more vividly than in all those songs organised around the grammatical structure: imperative verb + it.

To name just a few:

-

Whip it (Devo)

-

Push it (Salt-n-Pepa)

-

Beat it (Michael Jackson)

-

Work it (Missy Elliot)

-

Milk it (Nirvana)

-

Pump it (The Black Eyed Peas)

-

Pump it up (Elvis Costello)

-

Give it up (KC and the Sunshine Band).

The instructions in these songs seem straightforward enough. The problem though for the hapless listener is that it is not at all clear what the “it” refers to in such titles – and we are left to puzzle over what it is exactly we should all be pumping, whipping, pushing and giving up.

Dylan shows how it’s done

Arguably the “imperative verb” song par excellence is Bob Dylan’s Subterranean Homesick Blues. In this case, the command is absent in the song’s title, but is ever present in the lyrics:

Walk on your tip toes, Don’t try No Doz

Better stay away from those that carry round a fire hose

Keep a clean nose, watch the plainclothes

You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.

This song, with its rapid-fire catalogue of wonderfully random instructions, is a parody of all the conformity-inducing messages typically foisted upon youth – whether by parents, teachers, corporations, the government.

According to Dylan, to submit to all this instruction is nothing but folly. A life of obedience, he suggests in the song, leads only to drudgery: “20 years of schooling and they put you on the day shift”.

For singers like Dylan in the 1960s, it was music more than anything else that could provide an escape from all this abject oppression.

Hassled by rock

But 40 years on, one has to wonder whether music is now not so much the solution to the problem, as its cause. With all these instructions issuing incessantly across the airwaves – telling us all what to do, and not to do, what to take on and what to give up – rock music has become arguably as much a contributor to personal angst, as a creative outlet for it.

And so what might be the antidote for we the audience – the undeserving recipients of all this hassling, hectoring, and outright harassment? Is there any guidance to be found in the genre on this particular issue?

Certainly it would not be to do what the Master’s Apprentices once urged – to “Turn up your radio”.

Nor to accede to Joan Jett’s request in I Love Rock and Roll to “put another dime in the jukebox (baby)”.

Instead one is inclined to the urgings of some of rock’s more dissident voices.

The Smiths sensibly thought it was a good idea to “burn down the disco, and hang the (blessed) DJ”; and Ice Cube was on the money when he told us to “turn off that radio, turn off that bullshit”.

But for the sagest of advice of all, the last imperatives go to that arch rock skeptic, Frank Zappa:

- Stick it out

- Get a life … and

- Don’t eat the yellow snow!