A top environmental adviser to the Indian government has described the Gillard government’s proposed carbon tax as an “interesting mechanism” that may be useful for Indian climate policy makers.

With annual GDP growth of around 8%, India is the world’s fourth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases but has argued that developed countries should bear the most responsibility for reducing global emissions.

Despite that, it has committed to reducing carbon intensity (CO2 emitted per unit of GDP) by 25% from 2005 levels by 2020. India is vulnerable to sea-level rises that could devastate coastal communities and threaten an influx of millions of climate refugees from low-lying neighbour Bangladesh.

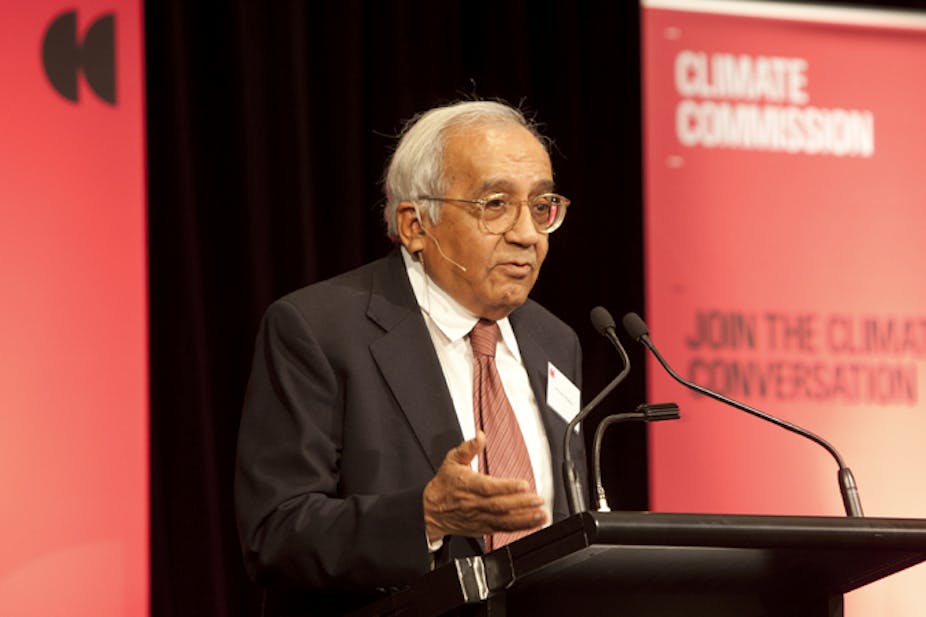

In this edited Q+A, Dr Kirit Parikh, chair of the think tank Integrated Research and Action for Development and former head of Planning Commission Expert Committee on Integrated Energy Policy for India, explains how India views the global climate debate and what emissions reduction policies it is pursuing.

Dr Parikh, a member of the Economic Advisory Council for five former Prime Ministers, visited Australia as a guest of the Australian government’s Climate Commission and spoke at a forum at Sydney Town Hall on Monday.

The voice of climate change skepticism appears to be getting louder in the US and Australia. Is this happening in India too?

No. For sure, we don’t have that much skepticism about it. Most people who are thinking about it are thinking this is a real threat. Not yet, the fringes have not yet surfaced in India.

Some people in Australia argue that why should our government act when countries like India and China are such big polluters. How do you respond?

India is not a big polluter. We are only emitting 1.3 tonnes (of greenhouse gases) per capita. That is one third of the global average and one twentieth of Australians and Americans.

I certainly agree that China and the US need to act very quickly. China is doing something, the US hopefully is doing something but not saying they are doing something. But we do hope the US takes much more aggressive action.

The importance of US action is that it creates momentum. The whole world, and especially developing countries aspire to the US lifestyle. So if the US lifestyle is made low carbon then that’s the model that is set for billions of people.

The big question is how do we allocate responsibility? Should it be by nation state? There has to be some sense of a per capita basis, some sense of collective social responsibility. I think per capita is a more reasonable, ethical and practical measure to do that.

There is also the issue of historical responsibility, the fact that between 1850 and 2006, India’s emissions are only 2% of the global historical emissions.

India is certainly the fourth biggest emitter but it has 1.2 billion people.

Some people also say there are now very rich people in India who consume a lot, and that is true. But even then the rich in India do not emit as much as the rich in Australia or the US simply because the infrastructure is not there – roads and other things – to indulge in the kind of luxury that is possible here.

And surely I would like that our policies will also constrain the wasteful lifestyles of the rich in India.

India has committed to reducing carbon intensity – CO2 per unit of GDP – by 25% from 2005 levels by 2020. What are the big policies that will achieve that?

The first is energy efficiency. There is a program to change all the incandescent bulbs, there is another program for labeling of all appliances with a star rating. Even industrial equipment is being rated in this way.

The second area is building and construction. We have an energy conservation building code which is currently voluntary but it will be made mandatory for large commercial buildings and certainly that will make a lot of difference.

The third measure is in the transport sector. There is promotion of mass transport, bus transport is being increased but the major thing we can achieve here is to provide a fuel efficiency norm, a fleet efficiency norm for car manufacturers.

Of course, there is also the renewables sector. So (the plan is to) not only reduce demand for energy but also provide electricity from renewable sources.

The (national carbon intensity reduction) target could go to 34% provided much more aggressive measures are taken. That would mean we need resources, we need technology and more international help in the form of funding and knowledge sharing.

What about carbon pricing?

In India, we simply raised the price of coal, every coal manufacturer must pay it. It’s like an excise tax. It’s a price on the coal miners and manufacturers, it’s a tax on coal, rather than a tax on carbon.

We would like to introduce an energy trading scheme for some large industrial firms, about 700 of them. They are being given a specific standard, a norm for reducing their energy consumption. Industries who achieve their target can trade (unused pollution permits). If it’s less, they can buy and if they don’t do it there is a penalty.

That’s about to be introduced, it is being finalised.

Do you think India will borrow any policy mechanisms from Australia?

Yes, I have seen what they are doing in Sydney, making cycling infrastructure and trying to have a city that is more densely developed. It’s good to see these things are being done.

The whole idea of the carbon tax that is being suggested by the Climate Commission is slightly different to what we have. The tax is paid by a limited number of people (500 polluting companies) and then (the government will) give it back as a rebate to a different set of people. That’s an interesting mechanism.

The mechanism has some ideas which would be useful for us in designing our policies.

How can India tackle climate change with such big subsidies on polluting fuels?

Oil products are not subsidised too much. There are some subsidies on kerosene because it’s used by people for lighting.

There is a lot of subsidies for LPG, which people use for cooking. There, I think, certainly it’s not justified. The richer members of society who use that should be asked to pay the full price and the subsidy should be targeted. That has been agreed in principle but has not been implemented.

For petrol, the price paid by consumers is far higher than the import price. Diesel is the only one where there is a subsidy, four or five rupees a litre. That is about 10c in Australia.

What do you think will happen at the global climate talks taking place in Durban later this year?

I am not very optimistic. I think maybe we can get a little more of what happened at Copenhagen.