This month’s tragic mudslides in Montecito, California are a reminder that natural hazards lurk on the doorsteps of many U.S. homes, even in affluent communities. Similar events occur every year around the world, often inflicting much higher casualties yet rarely making front-page headlines.

During my field research as a geologist, I have seen destruction from landslides firsthand in many parts of the world, including Nepal, China, Indonesia and Peru. In my view, these losses could be mitigated by improving our scientific understanding of landslides and debris flows (moving masses of mud, sand, soil, rock, and even sometimes ice), and by helping societies communicate the resulting risks more effectively – particularly in developing countries, where the damage is most severe.

Thousands killed in single events

The damage from landslides can be staggering. In the most destructive recorded cases of the 20th century, thousands of people died in single events. For example, catastrophic debris flows from Nevado Huascarán – the highest mountain peak in Peru – killed as many as 4,000 people in 1962 and another estimated 18,000-20,000 in 1970. Globally, the highest numbers of fatalities from landslides occur in the mountains of Asia and Central and South America, as well as on steep islands in the Caribbean and Southeast Asia.

Wherever slopes are steep, there is a chance that they will fail. Most of the time, the odds are low. But heavy rainfall or a large earthquake can destabilize precarious balances and unleash the raw power of tumbling rocks and debris.

The risks increase after wildfires, as we have seen in Montecito. They also can be exacerbated by deforestation and land use change. Earthquake-triggered landslides, while less frequent than those induced by rainfall, have been responsible for some of the greatest losses of life. During the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China’s Sichuan province, 20,000 deaths were attributed to landslides – roughly one-fourth of the total deaths from the quake.

The effects of smaller landslides also add up. Dave Petley, an earth scientist at the University of Sheffield, has calculated that landslides caused 32,322 fatalities between 2004 and 2010 – equivalent to over 4,500 deaths each year. For comparison, floods are estimated to have killed an average of roughly 7,000 people each year between 1975 and 2000.

Heavy tolls in developing countries

As with many natural disasters, the effects of landslides are disproportionately severe in developing countries. Between 1950 and 2011, debris flows killed an average of 23 people per event in developing countries, compared to 6 fatalities per flow in advanced economies.

This difference may reflect a number of factors, including the resilience of basic infrastructure and emergency services; the availability of health care to treat people who are injured or left homeless; and patterns of development that determine where people live. Improving basic economic conditions and construction standards in high-risk areas could go a long way toward mitigating losses from landslides, as well as from earthquakes, tropical storms and other natural disasters.

Early warnings save lives, but require data and models

Another major difference is that, at least in many cases, wealthy countries have early warning systems that can alert people to imminent risks. Casualties in Montecito would likely have been much higher in the absence of warnings from scientists and government agencies in the days and hours leading up to the tragedy.

The evacuation orders in Montecito were based on models for debris flow risk generated by the U.S. Geological Survey. The USGS uses decades of data collected from past events to predict how much rain is needed to start debris flows after wildfires in the Western United States. As a storm approached the California coast in early January, authorities used these debris flow hazard maps to issue advance warnings to residents in the Thomas Fire region near Montecito. Initial warnings came days before the mudslides occurred.

Then, at about 3:00 a.m. on Jan. 9, as a band of particularly intense rainfall approached the most susceptible areas, authorities issued an emergency alert for people to evacuate. The fact that these alerts came too late for some victims suggests that even U.S. emergency communication systems can be improved.

There has also been controversy over the fact that some evacuation orders in Montecito were mandatory and others were voluntary. And there is scope to improve both landslide hazard maps in the U.S., and to implement a much-needed warning system for earthquakes. Nonetheless, public officials had a lot of information about potential hazards – information that was critical to issuing warnings and getting many people out of harm’s way this month in California.

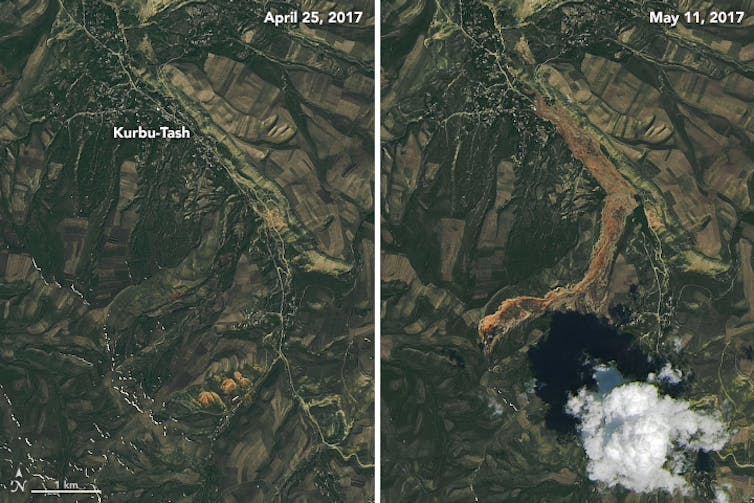

What would it take for developing countries to have similar opportunities? One starting point would be to improve understanding of when and why landslides are most likely to occur. For example, even though earthquake-triggered landslides cause enormous damage, we do not yet have a reliable framework for predicting landslides and debris flows following large earthquakes. Building better predictive models and using these to improve warnings of landslide risks could save hundreds or even thousands of lives in the future.

This scientific knowledge will be most effective if it is coupled with efforts to improve awareness of associated risks, and to build capacity and willingness for people to respond. These important parts of the puzzle are not easy to put in place in the United States, much less elsewhere.