The literary editor who, in 1957, advised Harper Lee to rewrite what has now been released as Go Set a Watchman undoubtedly did the right thing. As a literary work, the resulting novel To Kill a Mockingbird is certainly superior to the original Watchman, as many reviews have attested. But as a historical document, Watchman is a fascinating read. And the reaction to its 2015 publication gives us a valuable insight into how America prefers to remember its history of racism.

Watchman captures the moment in the mid-1950s when the determination of the Supreme Court to dismantle racial segregation across the South unleashed campaigns of massive resistance from southern whites. The ugly truth it captures, a truth which white Americans often prefer to forget, is that resistance to integration was not limited to a lunatic fringe of hardcore Klan members – the “poor white trash” that Atticus had been so steadfast in opposing in Mockingbird. “Respectable” whites, even ones who had a history of fighting for the better treatment of African-Americans, were part of the opposition to integration in the 1950s and 60s.

Racism on a spectrum

So Jean-Louise (Scout all grown up) is horrified to find the meeting of the White Citizen’s Council, the association that sprang up across the South to oppose integration, is full of “men of substance and character, responsible men, good men”. The Supreme Court’s determination to end segregation forced the gloves to come off: the racism that respectable white southerners had hidden behind a veneer of civility and good manners was suddenly cast aside. “You realize that our Negro population is backward don’t you?” Atticus asks his daughter:

Do you want Negroes by the carload in our schools and churches and theaters? Do you want them in our world?

As an account of the reaction of the white South to integration, and as a depiction of the limitations of southern liberalism – what we might now be allowed to call “Atticus Finch” liberalism – Watchman is a valuable text. Southern Liberals like Finch did indeed work in organisations such as the Committee on Interracial Cooperation (CIC) to ameliorate the excesses of racism which threatened the reputation of the south. But this did not mean they viewed African-Americans as equals and wanted to end segregation.

On the contrary, they thought a kinder, gentler form of segregation would preserve the racial hierarchy at the heart of southern life. Watchman’s elaboration of these gradations of racism is disconcertingly powerful. Atticus doesn’t want an African-American to be lynched, or even to be unjustly convicted of rape, but this doesn’t mean he wants African-Americans in his world, sitting next to him at church. Racism in Watchman is a continuum; a spectrum, not a fixed, yes/no position.

Blissful ignorance

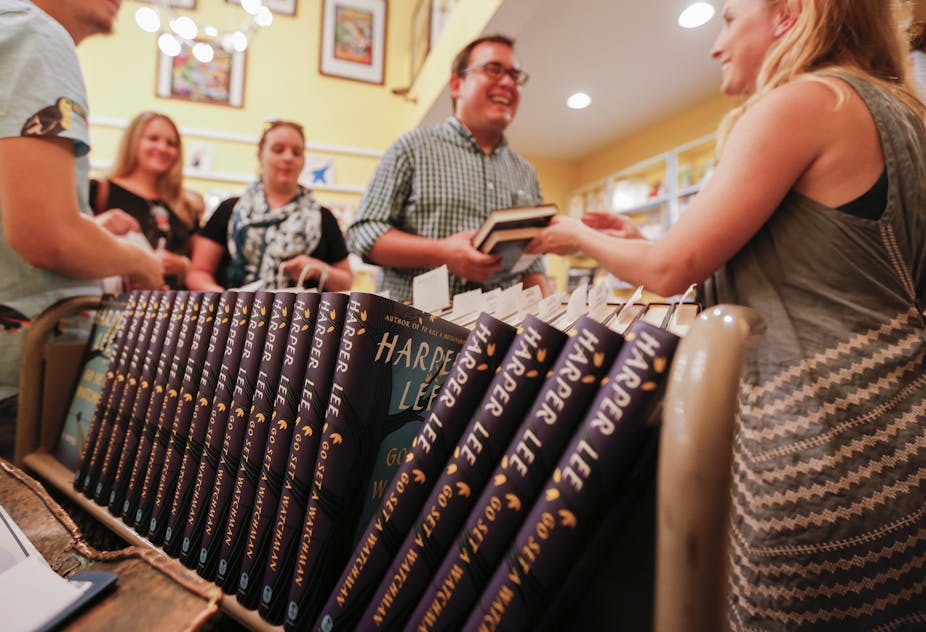

In addition to its depiction of white resistance to integration, reactions to the release of Watchman give us food for thought about the way white Americans today want to remember their history of race relations. The news that Atticus Finch turns out to be a bigot has been greeted with horror. Finch, so movingly portrayed on screen by Gregory Peck, was a much-loved character. Many fans of Mockingbird share his daughter’s horror that the saint-like defender of Tom Robinson is now determined to oppose integration. Devastated readers have pledged not to read the new book.

What does it tell us about America’s unwillingness to confront the realities of racism that it is a fictional liberal white man that is the hero of the seminal text on American racism? The horrified reaction to Watchman, this preference for “blissful ignorance”, exposes the reluctance of white Americans to understand that integration was a battle fought by actual African-American people, not fictional white men. And, yes, there were some white allies, but there were more white opponents. And not all of these opponents were comic-book southern racists, whose stupidity and ignorance marked them out as not like the rest of white America.

White Americans want to believe that Atticus Finch is real, because they want white people to have played a more heroic role in the struggle for racial equality than they really did. They are determined not to spoil their comforting tale of white heroism by a more nuanced – and accurate – understanding of what white southerners believed and what they did. The moral certainties of Mockingbird are more palpable to a white Americans still struggling to understand what racism and white privilege actually mean than the complexities of Watchman.