For the last few decades of the 20th century, the conflict in Northern Ireland looked intractable. Unionists and loyalists wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom, while republicans and nationalists wanted it to become part of a united Ireland once again.

Yet on April 10, 1998, after rounds of multiparty negotiations, a deal was finally reached in Belfast – the Good Friday Agreement. It would establish a path for paramilitary groups from both sides to get rid of their weapons and for prisoners to be released. It also paved the way for power sharing between unionists and republicans, and would establish a number of cross-border institutions between the north and south.

For the April 2018 episode of The Conversation’s The Anthill podcast, we asked four experts on Northern Ireland’s politics and its history to explain the role of some key players in getting the Good Friday Agreement across the line. Here are some extracts.

David Trimble

Our first key player is David Trimble. Back in 1998, he was leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, at the time the main unionist political party in Northern Ireland. Trimble had risen to the head of the party in 1995, replacing its longstanding leader James Molyneaux, and was initially seen as somewhat of a hardliner. Connal Parr, vice chancellor’s research fellow in the humanities at Northumbria University, explains Trimble’s role in the Good Friday Agreement.

John Hume

John Hume was the leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party – the main nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. Here’s John Morrison, director of the terrorism and extremism research centre at the University of East London, on Hume’s role leading up to April 1998.

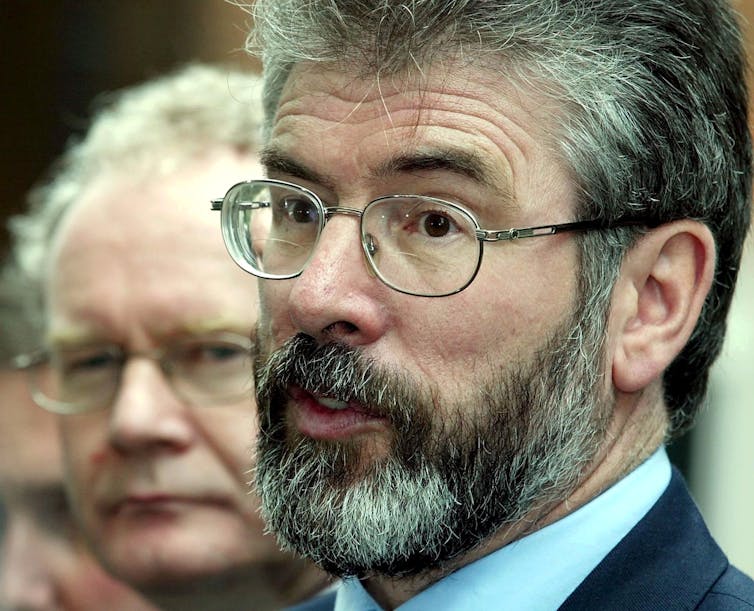

Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness

Gerry Adams, leader of the republican party Sinn Féin, and his deputy, Martin McGuinness, who would later become deputy first minister of Northern Ireland, played a key part in the agreement. John Morrison explains their journey from members of the Provisional IRA to leaders of Sinn Féin.

David Ervine

A former member of the Ulster Volunteer Force and later leader of the Progressive Unionist Party, David Ervine was an articulate voice within the working-class Ulster loyalist community. He was to argue in favour of the Good Friday Agreement, as Connal Parr explains.

Bill Clinton

It was the Americans who helped pave the way for the nitty gritty of negotiations. Here’s Liam Kennedy, director of the Clinton Institute for American Studies at University College Dublin, to explain the role of US President Bill Clinton in the Northern Irish peace process.

George Mitchell

Soon after he was elected in 1993, Clinton appointed Democratic senator George Mitchell as US special envoy for Northern Ireland. He would put his name to the “Mitchell Principles” that guided the negotiations, and played a key role in getting to an agreement. Liam Kennedy explains.

Bertie Ahern

Elected Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland in 1997, Bertie Ahern inherited the peace process from his predecessors. Margaret O’Callaghan, reader in history and politics at Queen’s University in Belfast, explains the work Ahern did to secure the peace deal.

Tony Blair

Like Aherne, when Tony Blair was elected in 1997 he was passed the reins of the peace process from his predecessor, John Major. But things began to change quite quickly, says Margaret O'Callaghan, as Blair got into deal-making mode.

Mo Mowlam

Doing a lot of the groundwork for Blair was his newly-appointed secretary of state for Northern Ireland, Mo Mowlam. Margaret O'Callaghan says that Mowlam’s subsequent portrayal since her death in 2005 as “marginal” to the Good Friday Agreement is unfair, and that she changed the weather, altered the atmosphere and got people to trust her.

There are of course a multitude of others who helped get the agreement over the line, including political parties such as the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition, an all-woman party that took part in the peace negotiations, religious figures, and, of course, the people of Northern Ireland, who voted overwhelmingly for it.

Click here to listen to the full version of The Anthill podcast on the 20th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement.