There are many qualities that have been suggested that separate human beings from other living species. These include tool making, an ability to dream and especially the development of highly sophisticated language skills. But as we learn more about animal life, the rudiments of such talents are described in other species. A truly distinguishing feature of our species is our ability to cry emotionally.

There are anecdotal reports of animals showing what we would refer to as grief, but Susan McCarthy and Jeffrey Masson show in their book When Elephants Weep that animals do not shed tears out of emotions. Tears have a biological purpose of keeping the eye moist. They are also packed with antibiotic substances helping minimise infections. They may even contain seductive pheromones, altering the sexual behaviour of one who gets too close. Yet elephants do not cry and no one has seen crocodile tears.

Crying: strength or weakness?

The ignominy of male tears has a long history. Greek hero Odysseus, on hearing the songs about the Trojan wars sung by Demodocus weeps, as Homer put it, like a woman. He hides his face from the rest of the company with his mantel, ashamed to be seen crying.

Crying is often seen as manipulative, a trick accredited mainly to women, as Shakespeare put it in The Taming of the Shrew:

And if the boy not have a woman’s gift To rain a shower of commanded tears, An onion will do well for such a shift.

The impression given is that crying is a female trait and associated with weakness, a theme repeated in various historical epochs. In plays and novels, the ideal tragic hero did not weep, being the paragon of the balance between reason and emotion. But I argue that crying tears is a precious human attribute with profound ethical implications.

Let the tears speak

Research on the when and why of emotional crying, such as that in the book Adult Crying, rehearses certain themes: separation, mourning, singing, institutional ceremony, religious occasions and such. Crying occurs in diverse places ranging from the church or temple to the theatre, from the concert or opera house to communal arenas such as the Olympic stadium. But most tears are shed at home, often alone or in the comfort of one other.

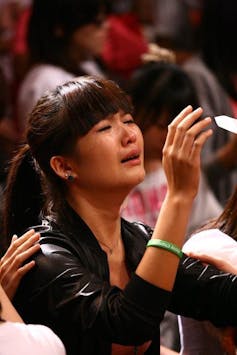

Crying is how humans communicate suffering. It primarily yields knowledge about the emotional state of another.

Although crying without tears is normal before about three months of age, the eventual release of tears, and the response of a mother to such a signal, have obvious benefits for the growing infant. The patterns of such early behaviour endure, becoming more controlled in adulthood, but which can be released by appropriate stimuli at any time in life. The reaction to separation or the loss of attachment is basic to all of us and may not change much from the age of 12 months to death.

In my book Why Humans Like to Cry, I suggest that crying to emotional events must have both evolutionary and neuroscientific explanations. It is the case that people cry when they observe others crying, as they laugh when others laugh. This could be just imitation, but it is more often than not linked with the appropriate feeling.

Based on arguments that only humans cry tears emotionally, in the book I have described differences between brain circuits that regulate emotions comparing the human brain to what is known about chimpanzee anatomy. These nerve pathways also give us “gut feelings”, which are so intimately bound in with sadness, grief and crying. This circuitry also links with brain structures that allow us to not only imagine the future, but to have memories attached to emotions.

Studies have shown that our ability to cry is closely linked with empathy. Mirror neurons have been identified that respond to the emotional expressions of others. Seeing others in pain evokes a sensation we refer to as empathy and is closely bound with this is compassion.

At one point in our evolutionary history, awareness of self and of the other became a part of our consciousness. From a neuroscientific perspective we have developed the ability to feel the sadness of others and to cry emotional tears. We need not be ashamed of our biological cultural heritage, even those men among us.