Co-written with Kate Burridge

One of this piece’s authors (Howard Manns), a migrant, obviously struggles with English and literacy issues. He thanks his lucky stars that pollies speak to him in simple, three-word slogans. But what makes for a good slogan?

Good political slogans have a slathering of ideology, a dash of linguistics and lashings of repetition. With this in mind, let’s take a trip through the goodies and baddies of slogans.

A slathering of ideology

The word slogan derives from the Scottish Gaelic compound of sluagh ‘army, host’ and ghairm ‘shout, cry’. The sluagh-ghairm served as a battle cry for Scottish Highland people, and usually involved shouting the hosting clan’s name or the location (hence the sluagh ‘host’ link).

Battle cries in politics tend to be catchy, pithy and frame a clear narrative for the electorate. The best slogans are social parasites, sucking up fear and uncertainty, and defecating false hope, change and progress. Good slogans say to the electorate, yes we can.

In fact, Barack Obama made all of these words his slogans in 2008. More so, the latter slogan, yes we can, tapped into deeper cultural links with the Spanish sí se puede, which was a rallying cry for the Latin American labour movement in the 1970s.

Our pollies adapt a similar strategy of tapping the cultural wellspring every time they spout off a mate, battler or fair go. The ALP briefly appropriated the national anthem in 1975 with its slogan Advance Australia Fair.

Good political slogans also tap into the personal and emotive and create villains and heroes. For instance, with axe the tax and stop the boats, we have short, emotive slogans that present us with villains in the form of people wishing to tax us or take our jobs but also mad monks willing to save us.

Yet, heroes and villains are often left unsaid and these slogans serve as dog whistles in the modern era. To these ends, we’ve come some way since UK politician Peter Griffiths in 1964 ran on the dreadful platform If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour.

A dash of linguistics

But what makes for a good slogan in terms of language?

Well, the repetition of the same or similar sounds is a good strategy (recall Obama’s victory speech and how “partisanship and pettiness poisoned our politics”). Moreover, the sounds one chooses can send subtle messages.

Some sounds just seem particularly appropriate to certain meanings. As Bob Cohen from the firm Lexicon once asked: Clorox versus Chanel — which is going to be the hard-working laundry detergent and which the new fragrance? Stopped sounds like p, t, k, b convey a sense of toughness (it’s not for nothing they dominate our swearwords). Of course, this means the slogans stop the boats and axe the tax are _p-, t-, k-_fully tough.

Vowel selection is also relevant here and a tough slogan would best avoid vowels like that in feet, which convey a sense of ‘smallness’, ‘beauty’ and ‘tenderness’ (you won’t find that vowel sound in any good swearword). Is this why Tony Abbott’s battle between the goodies and the baddies fell so short?

Aussies like posties and sparkies because this final -ies suffix adds a bit of intimacy and charm to a word. Yet, such suffixing is known as hypocorism, deriving from a Greek word meaning ‘to use child talk’, and this isn’t the best kind of talk to be doing when you’re shirtfronting.

Short and pithy is also important for slogans, and in linguistic terms, this means erring on the side of short (for the most part) Anglo-Saxon rather than long and Greco-Latinate words. This is why axe the tax and stop the boats make for better slogans than those that use words like Reconciliation, Recovery & Reconstruction (ALP, 1983), and, even worse, Incentivation (Liberals, 1987), which also lacks the magic three (an old rhetorical strategy and a staple slogan structure).

Lastly, it’s a political truism at this point that it’s not what you say but what people hear that matters. This means designing a slogan specific enough to define your era but vague enough that people can attach their own meanings.

This underlies Australia’s most successful slogan _It’s time _(ALP, 1972), which on the one hand flags the need for party change after 23 years of Liberal governance, but hints at a range of things the electorate might think it’s time for (e.g. new economics, new healthcare, new underwear).

To these ends, It’s time was more successful than the Liberal’s slogan, 23 years earlier, the more specific It’s time for a change (1949).

Lashings of repetition

Speaking of repetition, this year’s slogans are as Australian as apple pie and baseball.

The Coalition’s tiresome jobs and growth, while linguistically pithy and ideologically parasitic, is more a conservative mantra than a novel slogan. In the early noughties, George W. Bush used jobs and growth, brace yourself for some déjà vu, to promote tax cuts.

It’s easy to pick on the Coalition, who perhaps decided to play it safe after the continuity and change misfire, but the ALP is also guilty of political thievery and/or playing it safe in 2016.

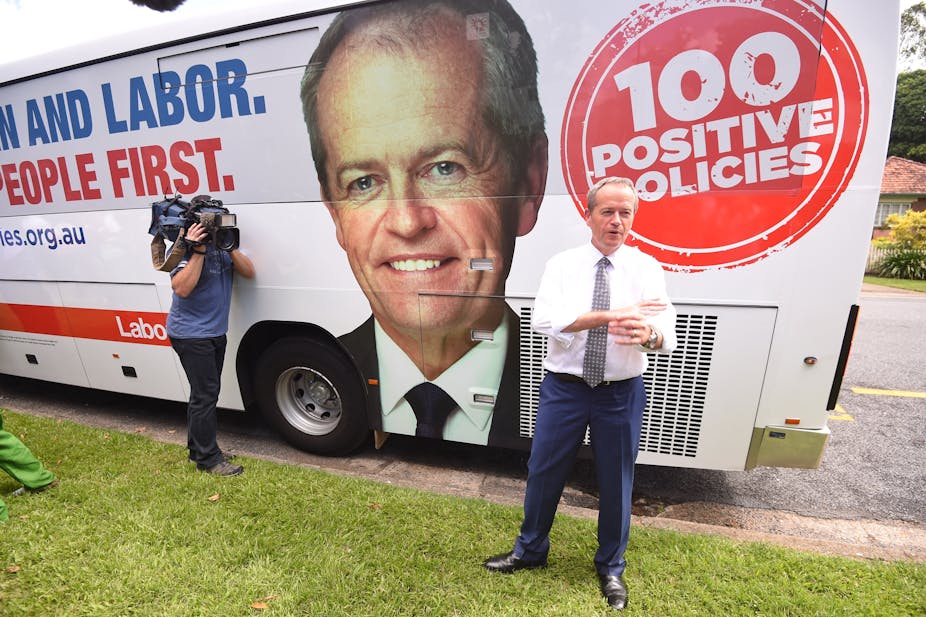

The ALP is using a slogan that echoes Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign, which promoted Putting People First. Twenty-four years later, Bill Shorten promises We’ll Put People First. We might read the shift from gerund (e.g. putting) to simple verb (e.g. put) as agility and innovation or as a reaction to Julia Gillard’s (2010) failed gerund Moving Forward.

Historical repetition of slogans, while on the one hand cringe-worthy, on the other is quite normal in electioneering. For instance, Abraham Lincoln famously invoked the proverb Don’t change horses midstream for his election (1864) in the waning days of the Civil War. Franklin Delano Roosevelt re-invoked it in the waning days of WWII (1944) and Bob Hawke used it against John Howard (1987).

Back to 2016, the ALP’s secondary slogan, 100 Positive Policies, hints at an issue political parties often grapple with: how to package what they offer. A second slogan of Clinton’s 1992 campaign was a New Covenant. It didn’t fly.

U.S. Republicans arguably nailed the right wording for its package with its 1994 Contract with America. The slogan’s architect, Frank Luntz, points out covenants are too religious and platforms too political. Plans don’t sound sufficiently binding and promises were made to be broken.

To these ends, 100 Positive Policies sounds like the subject line of a soul-sucking email from a human resources department. So, all and all, it’s looking like 2016’s slogans will go the way of the ALP’s 1961 slogan, which was (brace yourself for some déjà vu), Labor puts people first, both repetitive and forgettable.