By 2060, India may be the world’s largest economy. It will certainly be the world’s most populous country. At that point, Australians will ask, “What did we do in the 2020s to build a relationship with this superpower?” They may also ask: “How did economic cooperation with India benefit both countries in the early 21st century?”

The federal government’s report, An India Economic Strategy to 2035, was launched last week in Brisbane. Written by University of Queensland Chancellor Peter Varghese, it is an excellent basis for reflecting on these questions and the wider issue of Australia-India cooperation.

The strategy identifies numerous sectors - health, education, and tourism, for example - that can help enhance economic cooperation, and in which Australia has some comparative advantage. It also specifies ten Indian states as targets for collaboration based on their economic heft, commitment to reform, and relevance to the sectors in which Australia has competitive advantages.

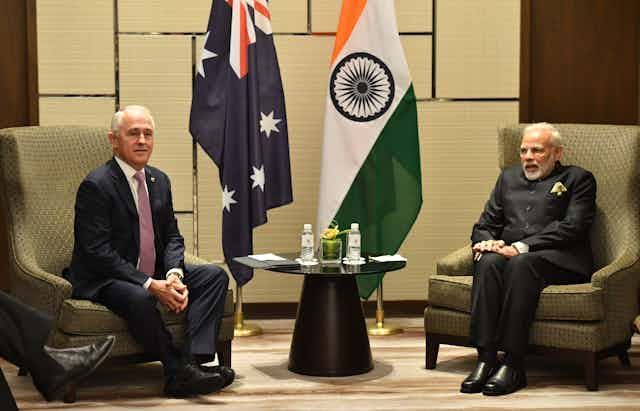

Importantly, the strategy is ambitious. It sets itself the goal by 2035 to lift India into Australia’s top three export markets. It intends for India to become “the third largest destination in Asia for Australian outward investment”, and for it to be brought “into the inner circle of Australia’s strategic partnerships.”

Read more: Why it's the right time for Australia and India to collaborate on higher education

The strategy emphasises two areas that need attention in order to meet these objectives. First, Australia needs to leverage the strengths of the Indian diaspora, which now numbers about 455,000.

The rapid growth of the Indian diaspora population can be a spur to economic cooperation. The Indian population in places like Silicon Valley drive the IT and biotech booms in India and the US. Canada is highly adept in enrolling its Indian diaspora in projects of national and international development.

Second, Australia needs to build more knowledge of India and support organisations that work on the bilateral relationship. While Australia made a pivot towards China in the last quarter of the 20th century, businesses, governments, and the public developed comparatively little knowledge about India.

The emphasis on China led to a neglect of India in education, media, and the policy sphere. There is a need to rebuild public understanding of India and the institutions that can activate this understanding to achieve lasting impact. Culture and arts will be very important here, both as a sector and enabler - points implicit in the strategy.

Varghese says we need to move beyond constantly drawing comparisons between India and China. “India is not the next China,” he writes. India is a distinct opportunity for engagement that merits discussion in its own terms.

The base from which Australia is working with respect to cooperation is certainly different: Australian exports to India are less than a sixth of those to China.

Two further issues will be crucial for the strategy’s successful implementation. The first concerns the relationship between growth and wellbeing. It is clear that the India Economic Strategy imagines enhanced cooperation not as a basis for economic growth as such, but also higher standards of living.

There is a need to reflect carefully here. We must think not only about spurring growth in the Australian and Indian economies, but also ensuring that growth is meaningful in four ways: that it addresses social and economic inequalities, creates jobs, is environmentally sustainable, and fosters opportunities to lead fulfilling social and cultural lives.

This is where the comparison between India and China is important. Since 2000, India’s economic growth has been not much more than half as effective at lifting people out of poverty as China’s economic growth. This means that for every 1% growth in Gross Democratic Product in China nearly twice as many people are elevated out of income poverty as in India. This partly reflects the depth of social inequalities in India.

Read more: Australia and India: some way to go yet

In the context of rising concern over inequality in Australia as well, the key question is: How can international economic cooperation create growth that reduces inequalities, generates jobs, and protects the environment in the countries concerned? It is a question that puts Australia and India on the same side of the table.

A second issue concerns the term “navigation”, which is in the title of the strategy. As the Danish anthropologist Professor Henrik Vigh has pointed out, navigation is a great metaphor. It connotes plotting and re-plotting a course on a moving plane. The complexity of that plane in this case calls to mind the six degrees of motion of a boat: pitch, roll, yaw, sway, heave, and surge. The strategy’s recommendations and ideas are excellent, and can be re-calibrated as India and Australia pitch, heave, and yaw.

The India Economic Strategy is an exciting document written with confidence and ambition. It provides a foundation for reflecting on economic cooperation and striving for meaningful growth.