All too often, graffiti is categorised as either art or vandalism, when in fact it’s so much more than that. When read with special attention, graffiti can offer deep insights into societies experiencing rapid social and political change – especially those marred by recent conflict.

The walls of a city give communities and individuals who may not have a formal platform space to share their feelings and opinions, and challenge dominant beliefs or ideals.

As researchers interested in societies recovering from disaster or conflict, we recently took a trip to explore graffiti in Cyprus. Cyprus and its capital, Nicosia, have remained divided since 1974, following the Turkish invasion and ensuing conflict.

The Turkish-Cypriot state in the north (recognised only by Turkey) is separated from the internationally-recognised Republic of Cyprus in the south by a UN-controlled buffer zone.

Crossings between the two sides are only permitted through closely monitored checkpoints, leaving the Cypriot people physically, politically and culturally divided.

In places like this, graffiti can both reflect and shape community attitudes at a grassroots level. By seriously examining graffiti as a cultural product of such societies, we can better understand these divisions and work towards peacebuilding.

The power of graffiti

Graffiti encompasses a wide variety of motivations and styles: anything from tagging to more artistic forms of expression like murals. Research has investigated how graffiti can be a channel for political participation and informal education. It’s a medium widely associated with urban subcultures formed around punk, hip-hop and skateboarding along with many other social movements over the decades.

Views about the value of graffiti can vary just as widely. Authorities, artists and members of the public tend to take different stances, which can also depend on context, content and style. Graffiti has sometimes been linked to social disorder and decline, but it can also add cultural value or in some cases lead to “artwashing” and gentrification. Certainly, it has the power to influence the character of a place, and change urban landscapes over time.

When searching for meaning in graffiti, we must look at its form and content. For example, pieces of plain writing may initially seem quite simple, but things like language choices can be telling.

In Nicosia, Turkish and Greek messages were painted with meaning for each respective “inside” group, while English was used to address a wider, international audience. So language choice is indirectly related to the ethno-nationalist conflict, and acts as an informal commentary on people’s experiences of the city.

Inevitably, we saw many references to division and conflict in the graffiti of Nicosia. But we also saw pieces related to local gang tags, local politics, anti-sexism and the patriarchy, racism, migrant worker rights, refugees, consumerism, veganism and LGBTIQ+ inclusion – among other topics.

This suggests local people are seeing beyond the past conflict in their daily lives. But it also suggests existing formal platforms for these issues to be addressed may not be effective or leave some feeling disillusioned. So people turn to city walls.

Making a statement

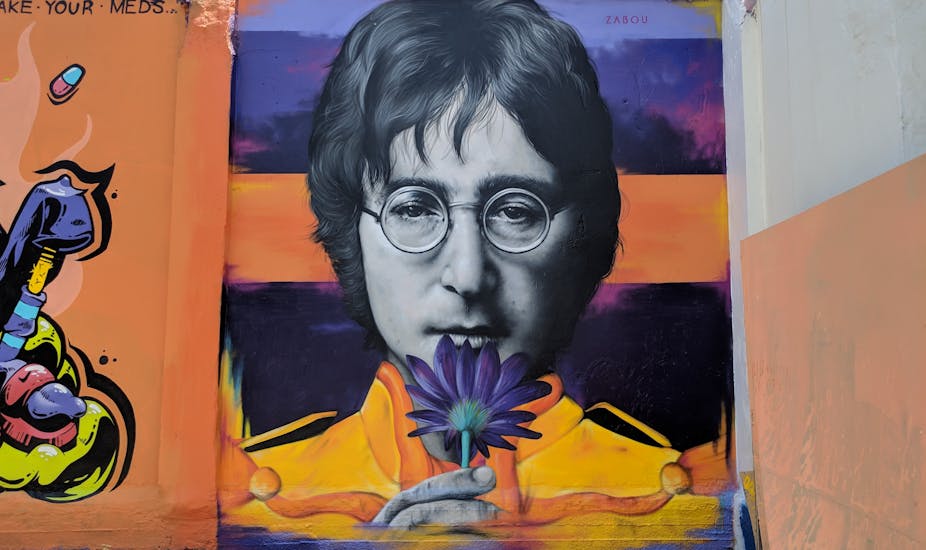

Larger scale murals across Cyprus are beautifully and skilfully painted – and equally interesting. In war-torn, damaged urban landscapes, they can be seen as an attempt to make the spaces more aesthetically appealing or to make a larger statement. These are often commissioned, and are even incorporated into official peacebuilding initiatives, art festivals and tourism strategies.

A mural in the southern city of Limassol, depicting a Nepali woman and her child, was painted shortly after the 2015 earthquake; unrelated to the Cypriot conflict itself, it affirms that Cypriot artists are outward-looking and aware of turmoil beyond their own borders (not always common in conflict zones).

Symbols are commonly used in street art across the world to deliver powerful political statements instantly. Internationally recognised symbols make a visual connection to transnational communities, ideologies and movements.

In Nicosia, common symbols included the Communist hammer and sickle, the Anarchist symbol, the peace sign, doves, gender signs and even swastikas. These symbols have broad, universal meanings attached to them so that no matter where the audience is from (Cyprus receives more than 3m tourists per year), the message is understood.

Location matters

Where graffiti is painted also tells a significant story: we saw that location influenced both the amount and the content of graffiti. The old city of Nicosia has lots of buffer zone walls and barriers, and a border crossing on the main shopping thoroughfare.

The areas closest to crossings contained mostly English language messages, explicitly about the conflict. Further away from the buffer zone, we observed less graffiti, and the messages become more varied.

We can speculate, then, that the division might have a greater influence on daily life, the closer people are to the dividing wall. This highly contextual insight has the potential to enhance our understanding of the unique experiences of local people in conflict-affected zones.

Our early investigations of graffiti have already told us much about life in conflict-affected Cyprus. Clearly, the importance of graffiti should not be overlooked: it can open a window into the lives and minds of many people, who might otherwise lack a voice.

This work is being presented at the Advancing Peace Geographies conference at Coventry University on July 15, 2019.