My early teenage summers were spent either on trips to India with my sister to see our friends and family, or at home in the UK. In either place they were full of long days spent reading on a veranda or in the garden, talking endlessly about who was seeing who, what happened last night, what kinds of relationships our futures might hold. Wherever we were, one or two volumes from a precious set of books came with us. Not maths or science, as perhaps our dad might have hoped. Lessons of a different kind were learned from the pages of Jilly Cooper novels, of which I still have a full set.

The reading pleasure I gleaned from the hundreds of pages of these books is incalculable. Their comic insight into the brutality of social pretensions is brilliant, and they have an escapist flippancy that makes them perfect for summer. Their literary value might be debated, but who cares? The cats and dogs in the novels are all named after composers, writers and artists: back then, that was enough.

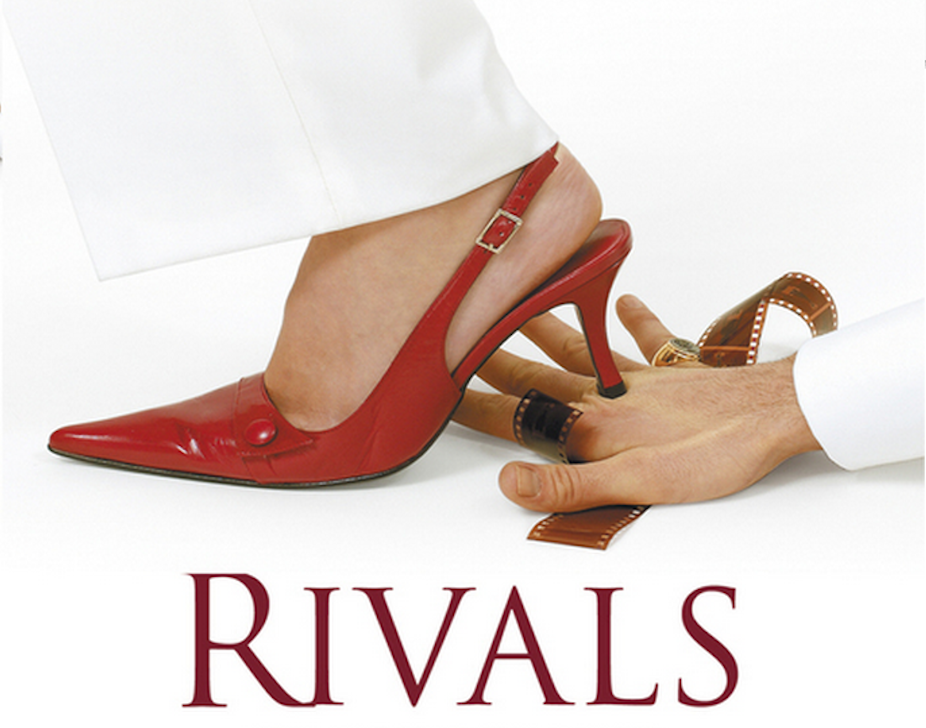

We waited to buy the latest one in duty free before the flight. Novels like Rivals could last eight hours in the air and a whole month of the summer, they could be put down after breakfast and picked up again to be read late into the night. Their one-liners made perfect comebacks and they are peppered with literary quotations by every great writer from Shakespeare to Dylan Thomas, to Yeats and even Catullus – “da mi basia mille” – yes, you can get Greek poetry in a “bonkbuster”. Those novels, with their racy covers and dry English wit, lent me a sense of much needed sophistication. This was money in the bank for a plump British Asian 14 year-old who wore glasses, and had a reputation for starting conversations with the line, “Have you read Jane Eyre?”

Girls like Bella, Emily, Harriet and Octavia could not have lead more different lives than two second generation immigrant teenagers for whom the word “boyfriend” may as well have been “unicorn”. But despite this they fed the hope that gauche, provincial girls could end up as London journalists; that Oxbridge welcomes girls on rickety bikes with dreams of becoming writers; that underneath manufactured female beauty often lies an insecure beast. So what if they all get their Alpha-man and lived happily ever after? Isn’t that the whole point of the promise of summer?

French kissing

I don’t read my Jilly Coopers anymore, but when I need the same top-up of romance and that tantalising dance of will-they, won’t-they, I turn to a novel by Françoise Sagan, better known as the 18-year-old author of existential teenage angst in Bonjour Tristesse. But who wants solipsistic teenagers for their holiday read? I can’t think of anything better than holing up in a Parisian café or stretching out on a Riviera beach with the spun-sugar confection that is Sagan’s lesser known novel, The Unmade Bed.

Sweet, addictive and absolutely written for summer, even its title suggests a time when rules are not so much broken as simply ignored. Sagan tells the story of frivolous Beatrice, a celebrated actress who can still get away with saying she is 35, and Édouard, the young playwright of celebrated, literary plays, who loves her beyond words. Sagan spares no one in her acute observations of vanity – she gives us two people who parody themselves, and whom society cannot stomach seeing together. Some think Beatrice is too old and too silly for Édouard; others say he is too naïve for such a cynical old survivor of sexual adventures. She is the older woman, clinging to her youth; she is unfaithful, petulant and manipulative – yet most of all she is afraid of admitting she can love. He is the true lover being slowly corrupted by society’s machinations. We understand this long before they do, and have to read almost through our fingers as the comedy of manners plays out.

Sagan’s comic perception is excellent; so too is her sense of the ridiculous, but her understanding of desire – that of her characters and her readers – is perhaps most potent of all. How about this for a holiday scene:

He was known, she was known, they had the right to share an order of Baltic herring at two in the afternoon in that artificially homely brasserie where such an act was tantamount to declaring: ‘We’ve just got out of bed we pleased each other, now we’re hungry.’

It’s the Baltic herring that makes this so funny – and the killing description of the “artificially homely” brasserie – who hasn’t spent summers in search of the perfect one of those? The final visceral line gives the whole piece a profound sense of truth by holding human vanity and desire up to the light.

Like Cooper, Sagan dusts her novel with a plethora of high-brow names. And it is exactly in doing so that the comedy arises. Beatrice and Édouard present themselves through a sheen of allusions to Proust, Paul Valéry, Shakespeare and Stendhal. They imagine their love affair as a grand narrative by some writer of literary status. In weaving these allusions into the story, Sagan pillories any aversion to mixing high and low culture and so adds a poignant humanity to her satire.

Some might say the novel is nothing but posh chick-lit, inappropriate for any serious reader more at home with the highbrow. But the last word on this belongs to Sagan (itself a pseudonym she borrowed from Proust). “The distinction, of course,” she writes in the novel, is “only the hair-splitting of intellectual snobs.” So with her blessing, I take this book to read again in my own summer bed.

Guilty Pleasures is a summer series in which academics reveal their most embarrassing cultural inclinations. Over the next few weeks, you’ll find out what literature professors delve into on holiday, when they can’t quite bear to crack into that next classic.