When writing his entry on John Olsen in his history of Australian art in the early 1960s Robert Hughes identified “… a streak of grease-paint” on the artist’s palette. This was front-line reporting from a young critic with a keen eye on current trends. Hughes was writing when the artist was in the midst of creating his celebrated You Beaut Country series and his comment alludes to both a performative facet in Olsen’s practice and his fear that the artist might slide into vaudevillian frivolity.

Most often Olsen’s dance with the brush remained a private, studio affair. It was evident in the traces left on the canvas — which echo Paul Klee’s famous description of drawing as “taking a line for a walk” — but the artist’s creative waltz as he cavorted around the canvas, brush and palette in hand, was rarely observed. What is remarkable about an important group of the You Beaut Country paintings is the inclusion of that performative aspect as an overt component of the project.

For a brief period in the early sixties, following his return from Europe, Olsen painted several ceilings around the eastern suburbs of Sydney. A glowing sun at their centre, drenching the room in a flood of Chromium yellow and pulsing with a miraculous life force, these murals were created in the presence of their patrons.

Much as Michelangelo had summoned forth the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel under the watchful gaze of Pope Julius II, so Olsen performed for his clients, Frank McDonald and Ann Lewis amongst them. Documented by photographer David Moore, his performance displayed the joie de vivre of his spontaneous “line walking”. As in Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, each line is modulated by the artist’s physical presence as his body moves through space brush in hand, seismically chronicling the world around him.

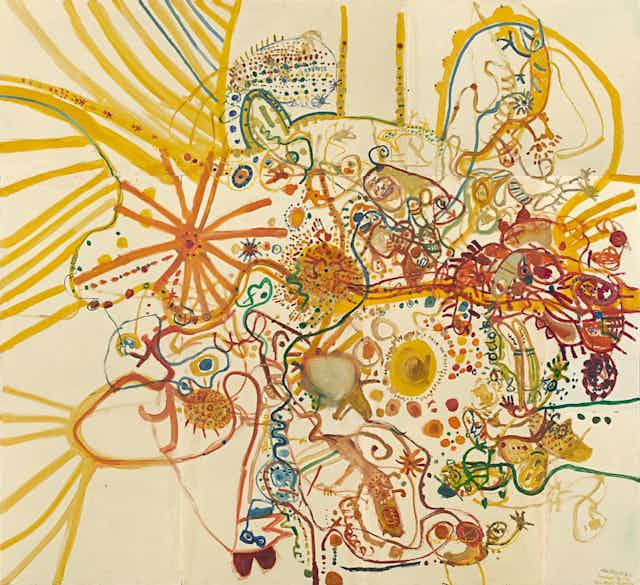

Indeed these early paintings are more accurately described as drawings. Liquid colour is traced across the surface with admirable dexterity. A yellow line becomes a blistering ray of sunlight, it then morphs into curvaceous topography before culminating in the form of a darting lizard. Other lines cross and merge to create a web of imagery, which, like a Mahler symphony, “… must be like the world. It must contain everything.” And they do.

Summer in the You Beaut Country, painted for Frank McDonald, is teeming with life. It has no horizon line, and the landscape spreads out like an aerial map, creeping further and further to the edges of our peripheral vision. Distracted from their glass of Chardonnay and glancing up to the boisterous life above, McDonald’s guests would have had a sense of being both above and distant while concurrently immersed and contained within the landscape.

One moment they were in the heavens scanning a vast topography, the next metaphorically on their knees examining beetles and scurrying lizards as the whole landscape coalesced, the sum of an infinite number of tiny incidents seen from multiple viewpoints.

During these in situ painting sessions, Olsen improvised energetically, riffing on his subject like a jazz musician. Lines radiate and pulse with syncopated energy, responding to all that he saw, heard and remembered. Often inspired by words from great poets like Gerard Manley Hopkins or TS Eliot, each encounter with the landscape was a quest for understanding:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

TS Eliot, The Four Quartets

Olsen’s journeys into the You Beaut Country are an exemplary exercise in re-knowing.

Despite the obvious influence of European heavyweights like Paul Klee and Joan Miró, Olsen’s paintings are often described as quintessentially Australian. Critics have pointed to their resonance with Aboriginal modes of mapping country, their larrikin swagger, the intense, colourful energy they emit, to their optimism, energy, and to their ebullience.

It is this latter joviality that Hughes’ sharp wit and razor-stropped nib identifies as a potential difficulty. “He does not deploy his swarming grotesqueries for laughs alone”, he writes, hinting that Olsen’s high-spirited, colloquial proclivities run along a thin edge separating the lyrical from the trite, and the profound from the vaudevillian.

Fortunately, Olsen is aware of this danger and most often steers south of that line to mine the undercurrent of danger Australians fear from grievous beasties and the untamed forces of nature. It was this contradictory beauty that fascinated him and his ability to finely tune the balance in the You Beaut Country series keeps them as relevant today as when he first painted them.

That same low rumble of imminent mortality we discover within the delicate melodies of Mozart is evident in these great canvases. As he explained to Virginia Spate “Art must make you laugh and make you a little afraid.”

John Olsen: the You Beaut Country is showing at the National Gallery of Victoria from 16 September 2016 to 12 February 2017, and the Art Gallery of New South Wales from March 10 to June 12, 2017.