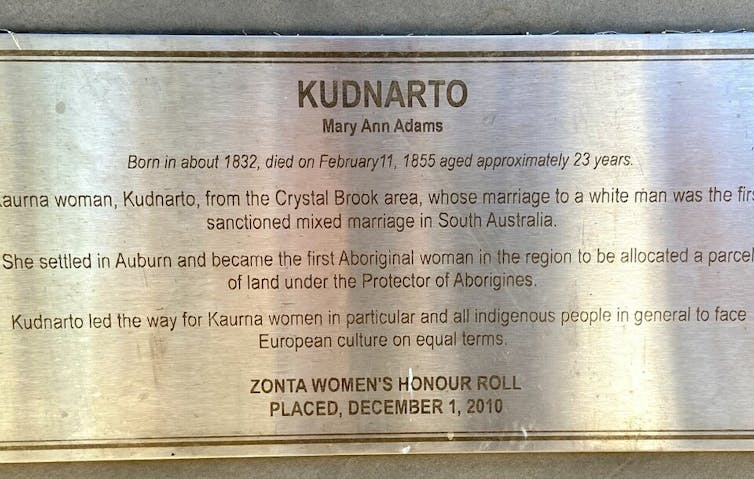

Kudnarto, a Kaurna woman, married shepherd Thomas Adams on 27 January 1848. Theirs was the first legal marriage between an Aboriginal woman and a colonist under colonial law in South Australia.

The occasion was recorded by The South Australian. The bride, who took the name Mary Ann Adams, wore

a neat gown and low boots. She wore no bonnet, but her hair was carefully dressed; and her whole appearance denoted cleanliness and comfort.

She was deemed “remarkedly good looking”, hardworking and well-tempered. Her English as she repeated her vows was clear.

Kudnarto was able to apply for Aboriginal reserve land for farming purposes under colonial law, so after their marriage Thomas put in an application for land on Skylogolee (Skillogalee) Creek, near Auburn in the Clare Valley.

In May 1848, Kudnarto (now Mary Ann Adams) acquired a license to occupy this land during her lifetime. This marriage set a precedent for other colonists to apply for Aboriginal reserve land on marrying an Aboriginal woman.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Wauba Debar, an Indigenous swimmer from Tasmania who saved her captors

Who was Kudnarto?

Who was Kudnarto, this woman who made legal history? Unfortunately we know very little about her, other than a couple of newspaper reports and her husband’s attempts to secure the land he occupied in her name.

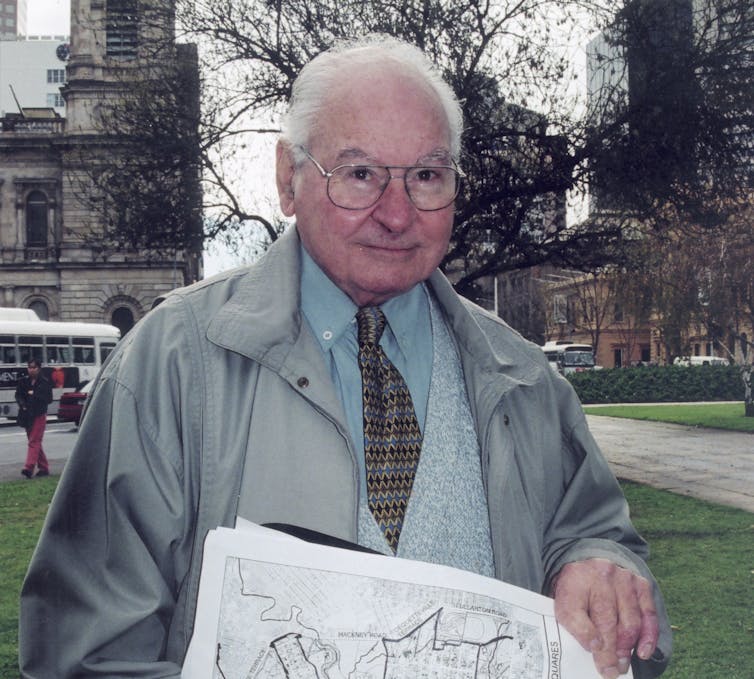

Her life is also remembered in a memoir, And the Clock Struck Thirteen, by her great-great grandson, Lewis Yerloburka O'Brien.

She was a Kaurna woman from the area around Crystal Brook, the northernmost region of Kaurna land, which extended across the Adelaide Plains to Fleurieu Peninsula in the south.

All that we know of Kudnarto’s Aboriginal family is that her name indicates she was the third-born child. Her father was probably a Ngadjuri man: the one written record of this is in the journal of anthropologist Norman Tindale. Lewis O'Brien says, “I’ve always known, however, that we’ve got Ngadjuri connections because everyone in the family used to talk about them.”

Kudnarto’s descendants include many prominent Kaurna community members, including Gladys Elphick, best known as the founding president of the Council of Aboriginal Women of South Australia, the first Aboriginal women’s body to be formed in Australia – as well as Josie Agius, one of South Australia’s first Aboriginal health workers, and AFL footballer Michael O'Loughlin.

A historic marriage

Kudnarto had spent her childhood on a settler’s property, where she gained some European education. As a young teenager she met Adams, 20 years her senior, and began living with him.

After they had lived together for about 18 months, Adams gave notice to the Deputy Registrar’s Office that he wished to marry Kudnarto. But first they needed the approval of the Protector of Aborigines, Matthew Moorhouse.

He visited Kudnarto several times to find out if she was fond of Adams and wanted to marry him. Moorhouse also instructed her on her marital obligations under British law.

He reported to the Colonial Secretary that “she likes him better than the black men” and gave his approval for the marriage, subject to the authorisation of the Lieutenant Governor for the marriage of an underage girl, which was immediately forthcoming.

The local newspaper reported on the upcoming nuptials in an ironically disparaging tone, giving us one of the few descriptions of Kudnarto, a personable woman: her “fidelity, amiability of disposition, and aptitude to learn, are very remarkable, if not unprecedented.”

There was one last hurdle to overcome: it was a condition of the marriage that Kudnarto go to the Aboriginal school in Adelaide, to be trained in domestic duties and build on the education she had already received.

Kudnarto’s land

Since the inception of the colony, sections of land in South Australia had been set aside as Aboriginal reserves, where it was anticipated Aboriginal people would farm the land. But there were continual pressures on the government to make the land available for colonists and many were leased out to them.

After the wedding, Adams wrote to the Protector of Aborigines, Moorhouse, requesting access to some of this land. His application was approved and sent on to Governor Robe. Moorhouse emphasised that he was representing Adams’ wife’s interests:

I would therefore respectfully ask on her behalf, that she may be allowed to settle on the Section in the Skylogolee Creek and have His Excellency promise that she be allowed to remain there so long as she lives upon the Section.

The Adams struggled to establish a farming enterprise. Thomas seems to have been a heavy drinker, with little training or experience managing property and he feared local people would shun him. Was he shunned because of his drinking, poverty or his Aboriginal wife?

After the birth of his first son Thomas (junior) in 1849, Adams wanted to find out whether Kudnarto’s children would inherit the land when she died. He was told that the original conditions for access to the land were to protect Kudnarto from desertion by her husband “with the understanding that there might be a renewal in favour of her children in case of her death”.

A second son, Tim, was born in 1852. Kudnarto, taught her sons “as much as she could” before she died.

We have very little subsequent information about Kudnarto. Her husband did illegally lease out the land while he sought work on other properties, but we do not know if Kudnarto and the children went with him, or where they lived.

Lewis O'Brien suggests

Kudnarto was still getting used to living in new circumstances without her family around and no game to hunt nearby. She had to live in the confines of a house with all these strangers passing across her land - it would have been difficult for her.

Witnesses to murder

In August 1850, Kudnarto and Thomas Adams were called as witnesses in a murder trial. As in the reports of her marriage, Kudnarto was treated as a test case for “civilising the natives”. Her appearance and demeanour were of note. Describing her clothes and hair, it’s reported that “she certainly appeared to considerable advantage”. She spoke clearly, although “in the idiom of her tribe” and her emotional responses to the crime were noted.

Kudnarto died on 11 February 1855, in her early 20s. Adams and his sons lost the right to occupy the land at Skylogolee Creek. Adams could not look after his children and took them to Poonindie mission on southern Eyre Peninsula, where they lived for the next few decades.

Both Thomas Adams senior and junior continued to make claim to the land on Skillogalee Creek. But their many applications were unsuccessful, despite those early promises that Kudnarto’s children might have rights to the land.

Lewis O'Brien reflects:

how many times do we have to own this country before we can say it’s ours? We’re the original owners. My great, great grandmother was given back a piece of her land, only for it to be taken away again from her family when she died.