The first Holocaust poems were written 90 years ago, when the full extent of the horror was yet to be known. Starting in the 1930s, those first works foreshadowed the catastrophe that was soon to come. As the second world war erupted and the Nazi killings began, people continued to write poetry that recorded direct experiences of persecution and lamented the murder of loved ones.

While many writers of Holocaust poetry are Jewish, there are those who belong to other groups targeted by the Nazi regime. Including those who were perceived to have disabilities, Roma and Sinti people, political and religious opponents and homosexual men.

Writing poetry of the Holocaust has often been a way to reclaim identity, as writer and translator Lou Sarabadzic puts it:

Victims of the Holocaust are not the Other in these lines, but rather the authors, the ones we listen to, the ones expressing emotions.

As such, they continue to be written today as people continue to reckon with the memories and impact of the Holocaust.

Diverse backgrounds

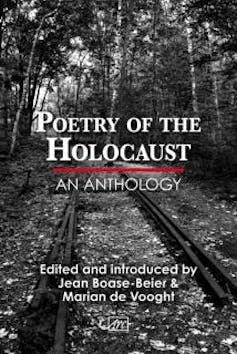

Published in 2019, Poetry of the Holocaust: An Anthology brings together poems from 19 languages that were previously unavailable in English. The translations in this book are followed by the original texts. These include poems in languages not normally associated with the Holocaust, such as Norwegian and Japanese, and from places like Argentina, Denmark and South Africa.

Holocaust poetry in the 1930s and through the war wrestled with the incomprehensible reality its writers were facing. The earliest poems in Europe responded to the foreboding of the fascist regime and its politics of elimination.

In 1932, the German poet Eduard Saenger wrote in reaction to the sinister change of atmosphere that he was witnessing in his country:

A silent wind sends fear through the land / with an edge like the howling of wolves.

Like Saenger, many wrote poems warning of the approaching dark times and also in reaction to specific events, like the book burnings of May 1933 and Kristallnacht in November 1938.

During the war, the poems documented life in ghettos, prisons and concentration camps. They spoke of mass shootings and of seeing neighbours deported.

Writing in the Terezín (Theresienstadt) ghetto in the early 1940s, the Czech teenager Dagmar Hilarová expressed the desire to die rather than undergo further humiliation and torture:

Like a bird with wounded wings / To lie down, / And not to wait for morning.

Poems written in concentration camps were memorised or hidden, often later found by others. Sallie Pinkhof wrote a poem in Bergen-Belsen in 1944, in which he mocked the state of his body:

What a hoot / these loose-fitting tendons / and bones in my foot!

Pinkhof did not survive but his poems were preserved by fellow camp inmates. An anonymous poem found in the Zigeunerlager (Gypsy Camp) of Auschwitz-Birkenau opens with the wish:

Do not wake me from my dream, / so the world need never know / how they treat a Roma.

Read more: Nazis murdered a quarter of Europe's Roma, but history still overlooks this genocide

After the war

For many the horror of the Holocaust is both lifelong and unspeakable. As the memory and impact of the catastrophe continue to be felt by survivors, their children and people touched by its reverberations, poems continue to be written about the Holocaust to express what is almost beyond words. Dutch poet Chawwa Wijnberg (2001), whose father was executed by the Nazis:

Always present is the unsaid / the unsaid / that rips the wound open

Silence is a recurrent theme. Rita Gabbai-Simantov, a Sephardic-Turkish poet who lives in Greece and writes in Ladino, Judaeo-Spanish, about Thessaloniki – “old Saloniki” – and its wiped-out Jewish community (1992): “As you walk, your companion / will be silence”.

After her visit to Auschwitz, the Lithuanian poet Janina Degutytė recorded in 1966 the enduring silence of the people who were deported from her country and murdered:

Lips gasp for air … / The only sound is the rustling of golden leaves, / The rustling flow of time: which was – is – will be …“.

Later poetry also gave voices to persecuted groups who were previously unrepresented. In 1995, French writer André Sarcq was the first to express the fate of gay men who for decades after the war, in France and elsewhere, could not speak about their experience in concentration camps. This was because homosexuality continued to be outlawed and they felt, in Sarcq’s words, like "the rag of a pool of souls”.

Poetry of the Holocaust continues to be written in our time. A striking example is the poem by Angela Fritzen, a journalist who has Down’s syndrome. Written after visiting an exhibition in Bonn, Germany in 2016, the poem is about the fate of people with disabilities during the Nazi era. “To have strength” is how Fritzen ends her deeply felt poem.

Holocaust poetry is a rich and diverse genre that continues to be added to. Both the older and the contemporary poems need readers, because Holocaust poetry is about communication. The poets felt the need to share their pain and it is vital that readers take the chance to empathise with what they have been through. By way of reflecting on the experience of others we recognise what it means to be human.

The translators of the quoted lines of poetry in this article are: Jean Boase-Beier (Saenger, Fritzen, Sarcq), Anna Crowe (Gabbai-Simantov), Maria Grazina Slavėnas (Degutytė), Marian de Vooght (Pinkhof, Sarcq) and Philip Wilson (Hilarová).