When George Osborne visited mainland China in 2015, the then British chancellor proclaimed it was a “golden era” of UK-China relations. This honeymoon between British and Chinese political elites is now in serious jeopardy because of recent events in Hong Kong.

On July 1, young protesters forcibly entered and vandalised Hong Kong’s parliament building, the Legislative Council. A key grievance was the Hong Kong government’s unwillingness to completely retract the proposed extradition law. Protesters were also enraged about police brutality during a previous demonstration on June 12. The British foreign secretary, Jeremy Hunt, called on the Hong Kong government to pause the extradition law, and to reflect whether it may “unintendedly” go against the letter or spirit of the Sino-British Joint Declaration signed in 1984 “that preserves the freedoms of the people of Hong Kong”.

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) summoned the Chinese ambassador to the UK, Liu Xiaoming, for a dressing down. Hunt also doubled down on his previous comments, stating that China could face “serious consequences” over the treatment of protesters. This triggered a ferocious response by Liu, who accused Hunt of a “cold war mentality” in an interview with the BBC on July 7.

What explains the rapid deterioration in the bilateral relationship? With Hunt in campaign mode in the Conservative Party leadership contest, his pronouncements over Hong Kong have been seen as election rhetoric by some. But such a view doesn’t reflect how Hong Kong has time and again been a major bump in the winding road of Sino-British relations.

One country, two systems

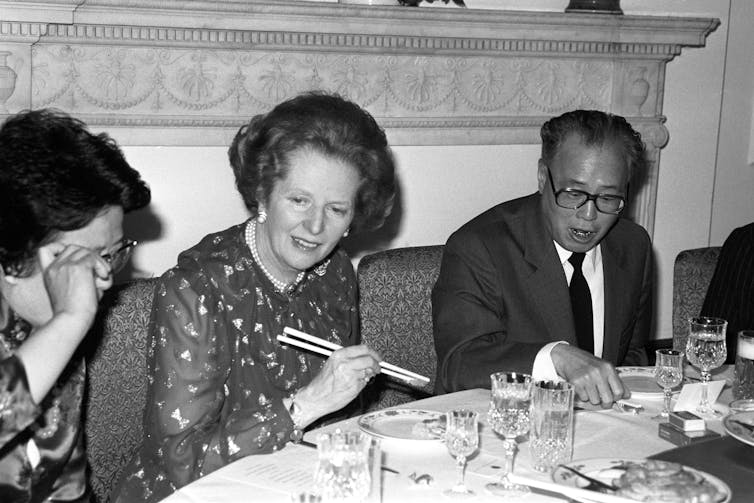

In 1984, a Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed by Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang and the British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher. It stipulated that after the handover in 1997, Hong Kong should enjoy a high level of autonomy until 2047. While the British side understood this legally binding international treaty as a mandate to speed up Hong Kong’s democratisation, the Chinese Communist Party raised objections to “the timing of the introduction of direct election” of Legislative Council members.

Such wranglings over the correct interpretation of the joint declaration took an unexpected turn in June 2019 when Liu declared this bilateral treaty a “historical document”, which had “completed its mission”. In London, this one-sided attempt to declare a legally binding treaty dissolved was met with incredulity, with questions raised about how seriously the UK government could take future commitments made by China.

At the heart of the current impasse are different assessments about the extent to which Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems” formula has been honoured by the Chinese side. Whereas Chinese officials such as Liu argue that Beijing has complied with the 1984 declaration, critics beg to differ. They point out that since 1997 the central government, with the active support of successive Hong Kong governments, has engaged in selective decolonisation. This is clear from the politicisation of Hong Kong’s education sector, the intimidation of independent media organisations, and the hollowing out of political institutions such as the Legislative Council.

The proposed extradition law is such explosive issue, because if enacted, it would tear down the firewall between the rule of law in Hong Kong and and the rule by law in mainland China, where the party-state plays the role of jury, judge and executioner. To make matters worse, Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, is ambiguously worded. This gives judges of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee in Beijing considerable leeway to interpret its stipulations in favour of the autocratic central government.

Read more: Hong Kong protests against extradition bill spurred by fears about long arm of China

Follow the US lead

Against this backdrop, questions remain over what the British government can do to uphold the one country, two systems formula. In 1989, the leader of the Scottish National Party, Jim Sillars, warned Thatcher that the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration was effectively unenforceable. While the FCO has been monitoring and reporting on Hong Kong every six months since 1997, such efforts have proven to be largely ineffective.

In order to give such reports more teeth, future British governments could consider adopting a similar approach to the bipartisan Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, reintroduced to the US Congress in mid-June. Once enacted it would make the “special treatment afforded to Hong Kong by the US Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992” contingent on the issuing of an annual certification of Hong Kong’s autonomy. The law would also require the president to identify those “responsible for the abductions of Hong Kong booksellers and journalists and those complicit in suppressing basic freedoms in Hong Kong”, to freeze their US assets and deny them entry to the country.

By adopting a similarly assertive stance the next British government could put considerable pressure on pro-Beijing politicians such as Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam. While she renounced British citizenship in 2007, her family members continue to enjoy British citizenship and her husband and one of her sons lives in the UK. A British version of the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act could provide a major disincentive for Lam and the Hong Kong government to escalate the crisis even further.