The prospect of Brexit has created many imponderables for the future of the EU’s relationship with the UK. At the same time, it also has significance for other international relationships. In particular, it is likely to impact trade and investment between the EU and China.

The UK has taken a leadership position in Europe in terms of its relations with China. For example, it has led European countries, in the face of opposition from the US, into membership of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. With Britain’s exit from the EU, China is losing a champion on similar trade and investment issues, which are central to its relationship with the EU.

In recent years, Europe has become an important destination for China’s outward foreign direct investment. Among the EU member states, the UK’s receptivity to Chinese investment is reflected in it being the recipient of the largest share of Chinese investment into the EU. The UK’s unique openness to investment from China includes investment in areas of critical infrastructure such as energy and telecommunications – areas considered sensitive by some other countries.

Although the response across Europe to investment from China has tended to be far more welcoming since the eurozone crisis, there remains considerable skittishness around such investment. This was evident last summer in Germany, with negative reactions to the acquisition of the German advanced manufacturing technology company Kuka by China’s Midea. That such reactions should have occurred in Germany, which has long been receptive to Chinese investment, indicates the potentially fraught nature of the environment for Chinese investment within Europe.

Concluding a comprehensive agreement

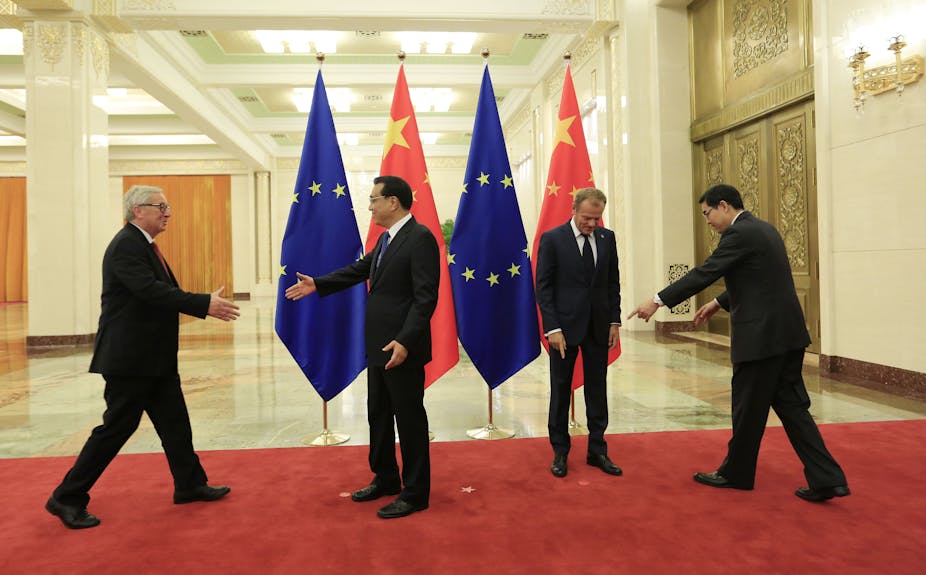

Since 2013, the EU and China have been engaged in negotiations to conclude a comprehensive investment agreement that covers investment from China into the EU and vice versa. So far, the two parties have agreed the scope of an agreement but not the actual terms of it.

The agreement covers the improvement of market access for European and Chinese investors. And it also addresses key challenges of the regulatory environment, including protection for investors and their investments.

With the UK’s exit from the EU, the question that arises from China’s perspective is whether – in the absence of a very supportive Britain – the remaining member states adopt a more restrictive stance to Chinese investment. They might be more demanding of reciprocity towards EU investment into China. If so, securing a comprehensive investment agreement may be more problematic.

Already, the EU Chamber of Commerce in China has pushed back against China’s strategy of developing national champions in ten advanced technology manufacturing sectors such as semi-conductors. This strategy involves heavily subsidising investments in and acquisitions of foreign companies, as well as forced foreign technology transfers in return for market access to overseas firms and requiring or encouraging customers in China to source from Chinese companies.

What now for the EU-China relationship

For similar reasons, China is concerned with its trading relationship with the EU. The EU and China trade more than €1 billion in goods every day. The EU is China’s biggest trading partner and China is the EU’s second largest trading partner after the US.

China was long unequivocal in its demand that the EU grant China “market economy” status under World Trade Organisation rules by the end of 2016. The UK has been a strong supporter of it having that status and establishing an open trading relationship. The UK was reluctant to support calls within Europe for the imposition of tariffs and restrictions on imports from China. For example, the UK was at the forefront in resisting calls for the imposition of higher duties on low cost imports from China – as in the case of steel, one of several sectors where China has over-capacity.

Again, the consideration that arises for China is whether an EU without Britain is likely to become less accommodating in its trading relationship with China. Plus, China, which has long sought a free trade agreement with the EU, is likely to find that without the UK, the EU will be even less inclined to move towards one than it already has been in the past.

As a consequence of Brexit, China is losing a key member state within the EU whose stance on matters related to trade and investment have been beneficial to China’s interests. Without the UK, the voices within the EU advocating a stronger assertion of EU interests with respect to China have been strengthened. China’s current over-capacity in a number of industrial sectors, already a source of serious concern for the EU, and its strategy in relation to its high-tech industries, are likely to be a source of greater friction between the EU and China.