Run a Google search on naturalist and preservationist John Muir and you will quickly turn up one of his best-known, yet abbreviated, sayings: “The mountains are calling and I must go.” It’s a compelling quote that says it all for many outdoor lovers, which may explain why it’s printed widely on mugs, t-shirts, posters and jewelry and paraphrased by today’s adventurers.

However, the shortened quote doesn’t fully capture John Muir or his desire to understand and protect California’s Yosemite – a grand glacially cut valley with sheer 2,500-foot walls, now federally protected as one of the oldest of the Sierra Nevada’s four national parks.

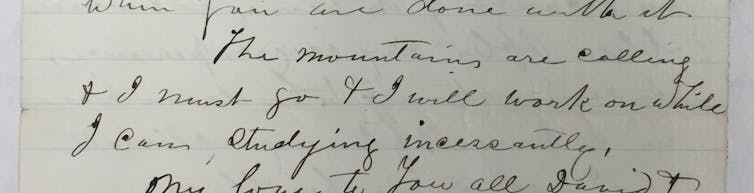

As we mark the anniversary of Muir’s birth on April 21, 1838, we should consider the full quote, which appears in an 1873 letter from Muir to his sister: “The mountains are calling & I must go & I will work on while I can, studying incessantly.” These words reveal a man who saw responsibility and purpose as well as pleasure in the mountains. Muir was a master observer who enjoyed the constant work of understanding nature.

As the curator of John Muir’s papers at the University of the Pacific, I help researchers to “study incessantly” these raw materials and get the full unabbreviated story. The papers reveal Muir’s determination to interpret and preserve nature, and his seminal role in the creation of the National Park Service which is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year.

You too can participate in not only understanding Muir but making him more accessible by transcribing his handwritten journals. We are enlisting citizen curators to harvest Muir’s words and make his journals keyword-searchable. Of course, the payoff for the transcribers is finding their own meaningful Muir quotation.

Revelry and science

Through Muir’s archives we can trace how his thinking about Yosemite evolved over almost half a century. He first mentioned the valley in an 1867 letter after an industrial accident left him temporarily blind: “I read a description of the Yo Semite valley last year and have thought of it most every day since.”

Muir, who was born in Scotland and grew up in Wisconsin, attended college briefly and “botanized” every chance he could get. He made his living as an inventor and efficiency expert, but the accident realigned his thinking. As he would later recall in his autobiography, he “made haste with all my heart, bade adieu to all thoughts of inventing machinery and determined to devote the rest of my life to studying the inventions of God.”

Before acting on those “every day” thoughts and going to Yosemite, Muir wanted to follow the footsteps of famed naturalist Alexander von Humboldt to South America, so he grabbed some books and a plant press, and started his “thousand mile walk to the Gulf” of Mexico from Indianapolis. However, a bout with malaria in Florida diverted his attention from visiting South America. He decided to make his way to California via steamship as quickly as possible.

Muir arrived at the granite cliffs of Yosemite in the spring of 1868. He was low on money but high on the majestic beauty of the granite faces, the mighty Giant Sequoia trees, and the roaring waterfalls. In a letter to mentor and friend Jeanne Carr, he wrote, “It is by far the grandest of all of His special temples of Nature I was ever permitted to enter. It must be the sanctum sanctorum of the Sierras [sic].”

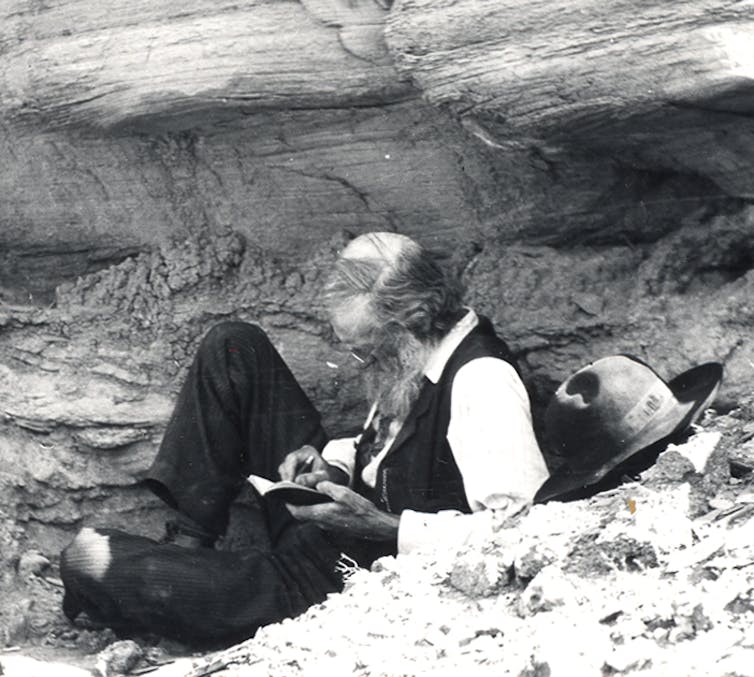

The Sierra had called, and he went. Muir studied the “Range of Light” incessantly for the next five years while living in Yosemite Valley. He understood that his studies could be risky – for example, he practically dangled himself over the top of the 2,500-foot Yosemite Falls in order to observe the motion of the water – but expressed no fear, exclaiming “Where could a mountaineer find a more glorious death!”

Muir’s intense observations deepened his understanding of the natural world and called him further into nature. Entering a grove of Giant Sequoias, the largest trees in the world, he wrote what historian Bonnie Gisel considers Muir’s pledge of allegiance to the wilderness:

The King Tree and me have sworn eternal love,… and I have taken sacrament with Douglas Squirrel [and drank] sequoia blood…. I wish I could be more tree-wise and sequoiacal, so I could preach the green brown woods to all the juiceless masses.

Muir used his observations to interpret the science of Yosemite and the Sierra. Before Muir arrived, California’s first geologists had theorized that Yosemite was created by cataclysmic dropping of the valley floor through violent earthquakes. But based on his studies and exploration, Muir concluded that glaciers had scraped Half Dome and carved the granite cliffs. Today geologists widely agree that glaciers were key forces in the origins of the valley.

Preserving the Sierra

In the early 1870s, Muir pulled his Yosemite observations together and published articles about the grand scenery. He preached his theories and called those “juiceless masses” to join him in the mountains. Years later he wrote, “[T]ry the mountain passes. They will kill care, save you from deadly apathy, set you free, and call forth every faculty into vigorous, enthusiastic action.”

Muir also began to call for protecting Yosemite and the Sierra. He saw major threats from loggers’ axes and the livestock industry’s “hoofed locusts” – his description of sheep that were overgrazing and destroying mountain meadows. Two years after Yosemite National Park was created in 1890, he cofounded the Sierra Club to preserve California’s greatest mountain range and make it more accessible.

Muir’s books and articles helped to promote appreciation of wilderness, and attracted political attention. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt visited Yosemite with Muir, hoping to “drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you.”

In 1908 Muir joined another president, William Howard Taft, in Yosemite, seeking to stop a campaign by the city of San Francisco to build a reservoir in the Hetch Hetchy Valley, which lay inside the national park. Muir declared in outrage,“Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.”

The battle to preserve the glorious valley was lost in 1913 when Congress passed a bill authorizing the dam. The loss practically killed Muir as well, and he died of pneumonia in a Los Angeles hospital a year later.

Summing up Muir’s legacy with the statement that “the mountains are calling and I must go” can suggest that he viewed nature as a playground. When he added, “& I will work on while I can, studying incessantly,” we see a more complete picture of Muir’s relationship with Yosemite. He viewed the Sierra with a combination of reverence and scientific fascination, but understood that its future depended on his efforts. Reading Muir’s writing carefully, we can recognize our continuing responsibility to observe, interpret, and celebrate the value of his “sanctum sanctorum.”