Net migration in the UK fell the most in the year to June 2017 since records began, according to new data released by the Office for National Statistics.

Perhaps Britain is starting to feel the pinch of “Brexodus”“. Or maybe it’s too early to tell. Having maintained and failed to meet the Conservative pledge to reduce net migration for the last seven years, Theresa May is likely to be relieved. But whether the opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn is pleased or troubled is unclear.

The Labour Party has been relatively silent on what post-Brexit immigration system it wants – or thinks the UK needs. But because Britain’s vote to leave the EU was partly fuelled by anti-immigrant sentiment, and the Labour Party has done little but fight internally about immigration since the 2015 election if not earlier, this silence is not surprising.

The party’s reticence and the factionalism on the issue are of its own making. To understand both why immigration is dominating the debate and how Labour got into this policy dilemma, we have to look back to immigration policy under Tony Blair’s New Labour.

Managed migration

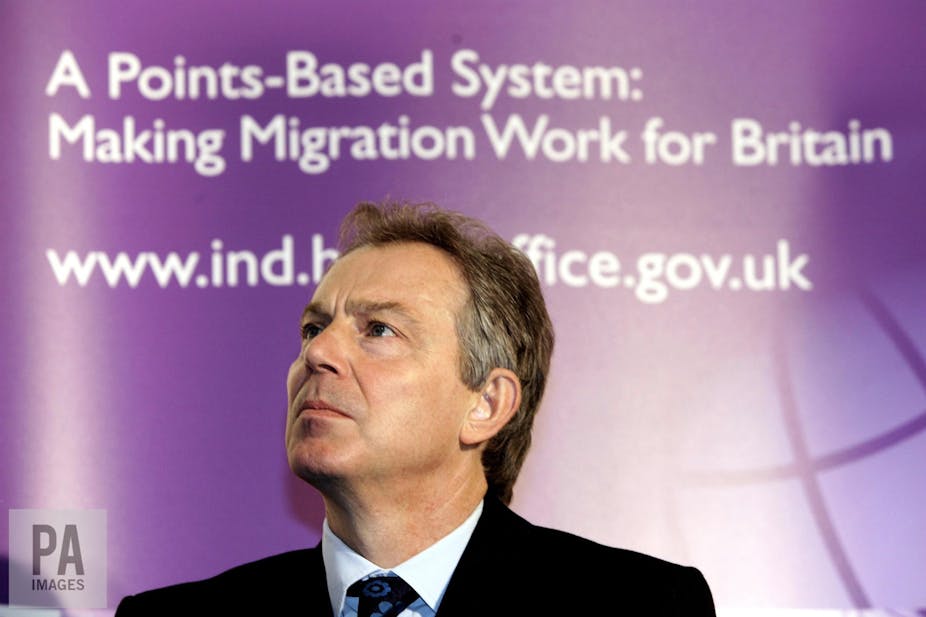

Under Blair’s Labour government, Britain’s economic immigration policy went from a highly restrictive approach to one of the most expansive in Europe, as I examined in new research. Work permit criteria were relaxed, the number of international students was doubled, the government expanded existing low and high-skilled migrant worker schemes and launched new ones and, from 2005, initiated a new points-based immigration system. Overshadowing these important reforms was the 2004 decision to allow citizens of eight countries that were about to join the EU the immediate right to work in Britain. This decision alone resulted in one of the largest migration flows in Britain’s peacetime history.

Put into historical context, Labour’s reforms were an unprecedented policy reversal. With 2.5m foreign-born workers added to the population since 1997 and net migration averaging 200,000 per year between 1997 and 2010 – five times higher than under the previous administration government of 1990-1996 – immigration under Labour quite literally changed the face of Britain.

Labour’s managed migration programme was certainly not a vote winner. Public concern about large-scale immigration contributed to Labour’s electoral defeat in 2010 and 2015. Such policies dogged Labour’s subsequent terms in opposition . In no Western country can a party appear to gain votes by favouring new immigration.

It’s worth emphasising that there was no plan or strategy within the Labour government to expand immigration policy when the party entered office in 1997. The final product of managed migration was a consequence of a number of policies from different departments. The Treasury and the Department for Trade and Industry pushed for high-skilled migration. The Department for Education and Employment bolstered the case for expanding international students. And the Foreign and Commonwealth Office shaped the infamous decision on the new eight EU members in 2004.

Combined, these policy schemes produced a liberalising effect on immigration policy. The government then pulled these schemes together to form a cohesive narrative of managed migration. But these reforms were nonetheless underpinned by an ideology – and this is the key to why policy evolved as it did, why the party is split on the issue now – and how Britain got on the road to Brexit.

New Labour, new times

At the heart of Labour’s infamous re-branding as New Labour in 1997 was the adoption of ”third-way politics“. This ideological reorientation is critical to understanding why economic immigration policy changed, because of three contingent elements of Labour’s new-found philosophy. First, the party’s neoliberal economic programme, hinging on measures to counter inflation and promote flexibility in the labour market. Second, Labour’s culturally cosmopolitan notion of citizenship and integration. Third – and fundamentally underpinning Labour’s economic programme and the inception of "new” Labour altogether – was an uncompromising belief in the inevitability of globalisation.

Economic globalisation was presented as an irreversible fact of life, and a natural development of capitalism that could not be controlled. According to Blair, the only “rational response” to globalisation was “to manage it, prepare for it, and roll with it”. Blair’s 2005 speech to the Labour Party conference perfectly encapsulated this pitting of the losers versus winners of globalisation. He said:

I hear people say we have to stop and debate globalisation. You might as well debate whether autumn should follow summer.

Labour claimed there was simply no alternative to globalisation. This logic trickled down to shape the objectives of many public policies. With immigration being “the human element of globalisation”, it was assumed to be both inevitable and intrinsically positive by the leading faction of the party.

Beyond New Labour

New Labour’s reforms brought immigration to the forefront of British politics – and debates on immigration will now remain a key fixture of the political landscape. To have any chance of winning office, Labour needs to win back its lost traditional working-class voters while retaining its liberal metropolitan so-called “Blairite base”. This is the progressive dilemma of Labour – one brought to the fore by New Labour’s immigration regime.

Blair’s narrative that people must adapt and move with the times or risk decline was clearly a winning electoral rhetoric in the 2000s. But this polarisation seemed to ignore the public’s desire for control, security and social order. When the financial crisis hit in 2008 – propelled by the globally interdependent financial systems New Labour helped to create – it is little wonder why much of the British public felt let down. They were alienated and angry at this global, open system for which many were certainly not seeing the benefits, only the costs. Immigration is one of the most concrete representations of globalisation – and therefore the easiest target for public antagonism in contrast to the faceless and abstract forces of neoliberalism, globalisation and austerity.

New Labour’s managed migration policy brought hundreds of thousands of immigrants to the UK, which has economically benefited the country and will culturally enrich society for generations. But the regime plays a part in the story of the politicisation of immigration and the road to Brexit.

In May 2017, Corbyn said that free movement will end after Brexit – but whether he wants this to happen is hard to determine. If Corbyn is to maintain that free movement will end, while retaining Labour’s ideological offer as the party of social justice, he needs a realistic policy on how to protect migrant workers’ rights in the face of likely surges in irregular immigration.

But more importantly, Corbyn should heed his predecessors’ lessons – giving economic solutions to what is, for many, an issue of identity is not a winning strategy. Corbyn’s Labour needs to craft a progressive narrative on immigration, one which makes sense with their ideology of tolerance, acknowledges the role of immigration in culture, identity, and nation-building, and makes sense in post-Brexit Britain.