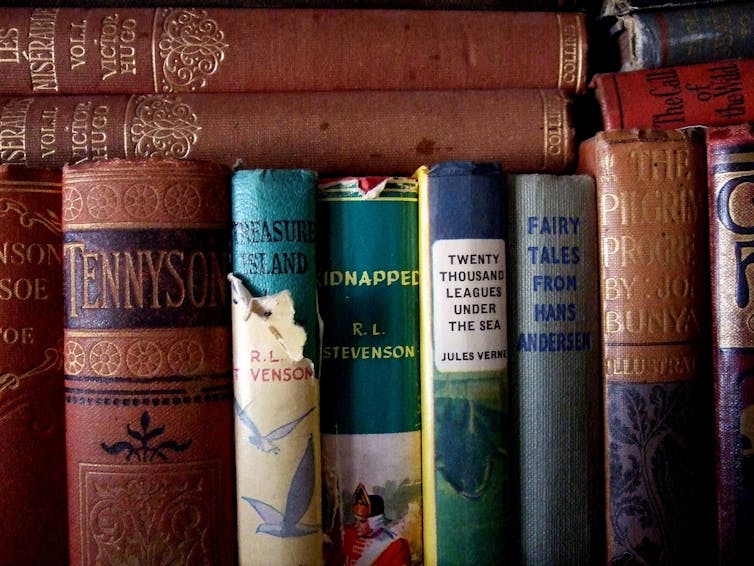

Ask most people about the heavyweights of late Victorian fiction and they will probably mention the likes of Thomas Hardy, George Eliot or Oscar Wilde. Raise Robert Louis Stevenson, however, and you’ll struggle to attract more than dusty affection: his work is usually seen as the stuff of old illustrated copies of boys’ adventures such as Treasure Island and Kidnapped, left in the forgotten corners of people’s attics.

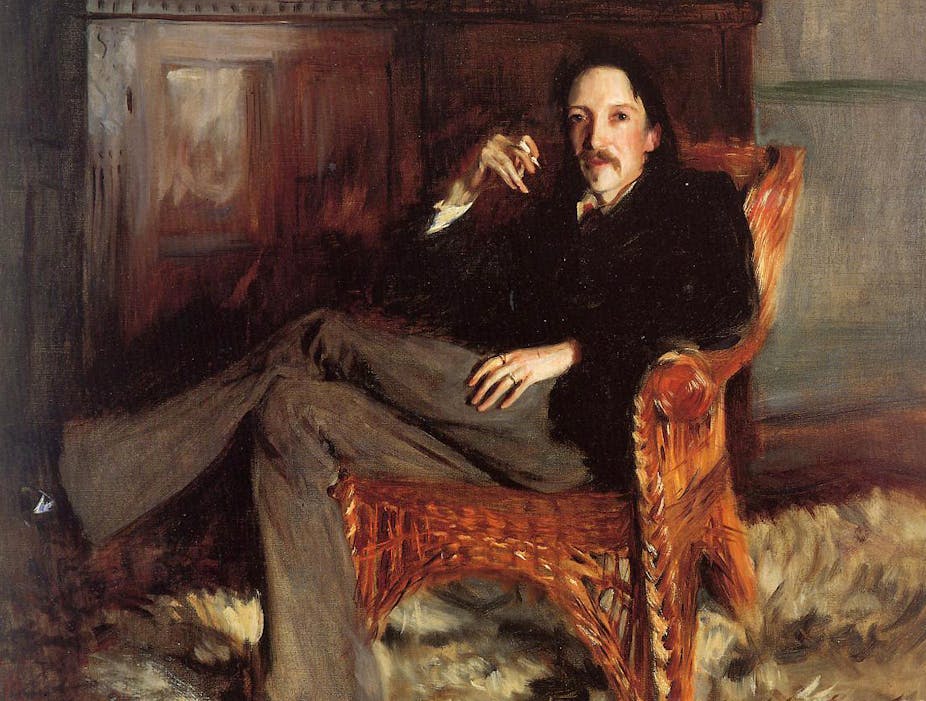

It was very different in Stevenson’s lifetime. The Scottish writer was renowned as an essayist and belle-lettrist like Henry James, who himself regarded Stevenson as an equal in intellect and talent. Stevenson’s subsequent journey to the lightweight fringe was no accident either. You can trace it through a series of decisions and events that demonstrate an unsettling truth: once you are no longer here, there is little you can do to protect your literary reputation.

When Stevenson died aged just 44 on Samoa in December 1894, reportedly of a brain tumour, the Victorian literary world was reeling. James wrote of the “ghastly extinction of the beloved RLS”. In Samoa, Stevenson had been known as “Tusitala”, the teller-of-tales, and his obituary in the Illustrated London News lamented his passing as such:

He is gone, our Prince of storytellers – such a Prince, indeed, as his own Florizel of Bohemia, with the insatiable taste for weird adventure, for diablerie, for a strange mixture of metaphysics and romance.

Sugared Stevenson

The high praise was not to last. After Stevenson’s death his family, notably his wife Fanny, and literary friends such as Sidney Colvin, began to manage and manipulate his legacy. When Colvin published Stevenson’s letters, he had redacted material they thought unsavoury, including the writer’s disputes with his family and his salacious youthful activities.

Probably motivated by a desire to protect the lucrative revenues from those boys’ adventures, this sanitised his image. It made him more palatable for a moralistic Victorian readership, securing his reputation as a non-controversial writer of children’s fiction. In 1901 Stevenson’s great friend, the poet and critic WE Henley, decried how he had been turned into a “seraph in chocolate” and a “barley-sugar effigy”.

Stevenson quickly became a target for other leading writers. Joseph Conrad denounced him, declaring to his agent, JB Pinker: “I am no sort of airy RL Stevenson, who considered his art a prostitute and the artist no better than one”. The American writer Stephen Crane was particularly disparaging, claiming: “That man put back the clock of English fiction fifty years”. Even HG Wells wrote that Stevenson’s interest in the romance tradition was a “pitiful instance of the way in which wrong-headed flattery, a feminine book market, and a man’s own talent may triumph over his genius”.

Whether they were inspired by Stevenson’s image-makers is unclear, but these writers were certainly in the vanguard of a new generation who felt the need to distance themselves from their Victorian forebears. Stevenson was also phenomenally successful, so professional jealously may also have been a factor. It set the tone for a long period in which he was frequently seen in the same kind of way.

The case for Robert Louis

Stevenson’s work is actually far more complex and wide-ranging than these reductive assessments allow. For Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde alone, he should be regarded among the great British writers. A book of massive influence and endurance, Vladimir Nabokov believed that it “belongs to the same order of art as […] Madame Bovary or Dead Souls”.

Treasure Island itself is more than meets the eye. It is actually a deeply subversive story of betrayal and divided loyalties, which deserves close reading. And beyond these household names, Stevenson also produced groundbreaking work that the likes of Wells and also 20th-century literary scholars unaccountably overlooked. Published in the year that he died, The Ebb-Tide is a dark tale of tyranny and imperial mismanagement, which anticipates Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and signals how Stevenson was beginning to question the morality of European interference in the Pacific. Together with the similarly themed The Beach of Falesá, it shows that had Stevenson lived, he could have gone on to rival even Conrad as an imperial sceptic.

Stevenson incidentally had a strong influence on his literary critics. Conrad and Ford Madox Ford used the opening page of Treasure Island as the model for the first sequence of their collaborative 1903 novel, Romance, actively seeking his fame and fortune whilst diminishing his art. As for Wells, The Ebb-Tide is a considerable inspiration for The Island of Doctor Moreau, while The Invisible Man owes a great debt to Jekyll and Hyde. Put these arguments together and you begin to see why he was never denigrated in the same way overseas. Particularly in America, France and Italy, he has always been seen as a great writer.

Some more recent writers were kinder about Stevenson. Ernest Hemingway was a fan, for instance. Jorge Luis Borges considered him “among the greatest literary joys I have experienced”. In the 1990s he began to be welcomed back into the fold in literary academic circles. This was led by the likes of Alan Sandison and the rise of cultural studies, which argues that “high” and “low” culture are completely interdependent and don’t fit into separate boxes.

More than a century after his death, it finally feels like we have reached the point where Stevenson is fully gaining the reputation he so richly deserves. We at Edinburgh Napier University are playing our part with the Mehew Robert Louis Stevenson Collection of his books and papers, which officially opens to the public on March 17. For one of Scotland’s greatest writers, his homecoming is long overdue.