Mrs Beeton would have been a disaster on Great British Bake Off. In her first published recipe – “A Good Sponge Cake” – the famed Victorian domestic goddess forgot to explain how much flour was required. Hardly a trifling oversight – but nothing that would have troubled Bake Off finalists, Jane, Andrew and the winner Candice, who sailed triumphantly through the final episode’s technical challenge of baking a perfect Victoria sponge without a recipe.

All three contestants produced tempting, golden confections filled with silky butter cream, alongside the requisite jam. The remaining challenges continued the Victorian theme – the bakers recreated Victoria’s coronation crown in meringue and filled a hamper with regal picnic treats.

We have a sweet tooth

The food historian Alysa Levene reports that Queen Victoria truly did enjoy a Victoria sponge, decorated with a single layer of jam, alongside other cakes and edible treats, at tea parties on the Isle of Wight.

According to a tell-all biography of Victoria composed by “a member of the Royal household”, she was particularly fond of “chocolate sponges, plain sponges, wafers of two or three different shapes, langues de chat, biscuits and drop cakes of all kinds, tablets, petit fours, princess and rice cakes, pralines, almond sweets, and a large variety of mixed sweets”. This perhaps explains her 50-inch waist.

Battenberg cake, on the other hand, which featured in the second series of Bake Off, is said to have originated as an homage to the marriage of Prince Louis of Battenburg to Queen Victoria’s granddaughter.

In fact, as the culinary historian Ivan Day has demonstrated, the earliest versions of that cake bore no resemblance to the checker-board design familiar to today’s Battenburg lovers. The first recipe for a “Battenburg cake” that he has discovered is a sort of fruit-cake. The first Battenburg to feature the cheerful windowpanes of different coloured batters called for nine cubes, rather than four; confusingly, a four-pane version also existed, but this was called a Neapolitan Roll.

Other versions were known, not surprisingly, as “Domino Cakes” – so the connection between Queen Victoria and Battenburg cake is tenuous, it must be said.

Of course, Victoria herself is unlikely ever to have turned her hand at baking. According to the aforementioned biography, such matters were left to the team of confectioners and pastry chefs who kept her supplied with “the cakes and biscuits which, four or five times a week, follow Her Majesty to Balmoral, Osborne, or wherever else she may be staying”.

The Queen-Empress laid down something of a standard for the royal tea table at her wedding to Albert in 1840. The royal wedding cake weighed nearly 300 pounds, had a circumference of 36 inches and was about 14 inches in depth or thickness. Ornately decorated with foot-high scale models of the happy couple and myriad dogs, doves and cherubim, the cake is reported to have cost £100 (more than £7,000 in today’s money). But clearly time and royal history has given this particular confection added value: a slice of the cake sold in September 2016 for £15,000 at auction along with a presentation box and the Queen’s signature. For comparision the two cakes served at Kate and Will’s wedding reportedly cost the taxpayer a reported $65,000. A slice of their elaborate eight-layer gateau recently sold for US$7,500 (£6,000) at an auction in Beverly Hills.

Victoria sponge

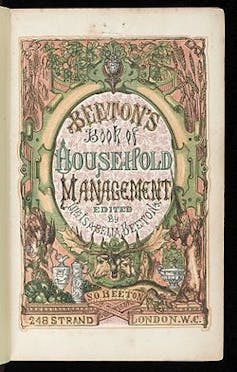

An early recipe for Victoria sponge appears in Mrs Beeton’s 1861 Book of Household Management, which achieved sensational and enduring success, despite Isabella Beeton’s rocky start with sponge cakes. The instructions note specifically that the resultant cakes should feed five or six people – presumably, fewer if Queen Victoria herself was among the party.

Ingredients: Four eggs; their weight in pounded sugar, butter, and flour, a quarter of a saltspoonful of salt, a layer of any kind of jam or marmalade.

Method: Beat the butter to a cream; dredge in the flour and pounded sugar; stir these ingredients well together and add the eggs, which should be previously thoroughly whisked. When the mixture has been well beaten for about ten minutes, butter a Yorkshire-pudding tin, pour in the batter and make it in a moderate oven for 20 minutes. Let it cool, spread one half of the cake with a layer of nice preserve, place over it the other half of the cake, press the pieces slightly together and then cut it into long finger-pieces; pile them in crossbars on a glass dish and serve.

Time: 20mins. Average cost: 1s, 3d. Sufficient for five or six persons. Seasonable at any time.

Proof of the pudding

I tried my hand at royal bakery, using Mrs Beeton’s directions. Unlike modern sponge cakes, her recipe employs no baking powder or other leavening agent aside from the eggs. Baking powder, invented in 1843, did not become common in cakes until some decades later.

I was curious as to how well Mrs Beeton’s version would rise. The batter puffed up enthusiastically, but unevenly, and an extra five minutes in the oven was not enough to prevent the cake from being what my Austrian grandmother would have called “mürbig”, or underbaked. No plaudits from the Bake Off judges are likely to come my way should they materialise in my Midlands kitchen. In future, I shall stick to Mary Berry.