In both the lead up to and the immediate aftermath of the US presidential election, President Donald Trump made claims of voter fraud and a rigged election, using all channels available to him, including Twitter. Despite the apparent lack of evidence for these accusations, they have arguably influenced the beliefs of millions of Americans.

Twitter has been a primary means by which the president has sought to set the agenda. Since he first took office, many people have speculated that some of Trump’s tweets were deployed to distract from negative media coverage. For example, when the press reported on the US$25m Trump University settlement, he tweeted about the Hamilton play controversy. When COVID-19 failed to “just go away” but instead took a stranglehold on the US, he tweeted about the “OBAMAGATE!” conspiracy theory.

At least some of these distractions seem to have worked. For example, our previous research showed how there was far greater public and media interest in the Hamilton controversy than the Trump University settlement. But the evidence had been anecdotal – until now.

Our new research presents the first empirical evidence that Trump’s tweets systematically divert attention away from topics that are potentially harmful to him. Perhaps even more importantly, we found that this diversion works and suppresses subsequent coverage of potentially harmful news stories.

We asked two questions: is potentially harmful media coverage followed by increased diversionary Twitter activity by Trump? And does such diversion reduce subsequent media coverage of that topic?

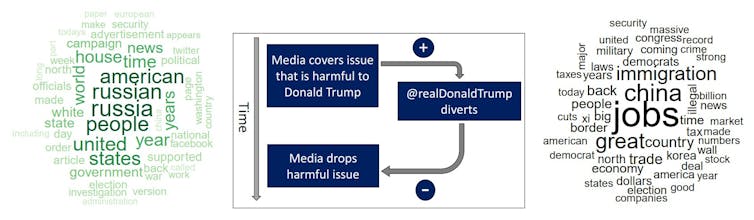

To test the hypotheses, we focused on the content of the New York Times (NYT) and ABC World News Tonight (ABC) headlines and all of the approximately 5,000 Trump tweets during his first two years in office. We chose the Mueller investigation into potential collusion with Russia as the harmful topic. We then selected a set of keywords – “jobs”, “China” and “immigration” – that we assumed would be Trump’s go-to topics at the time, based on a systematic content analysis of his campaign materials and major talking points.

The team hypothesised that the more the NYT and ABC reported on the Mueller investigation, the more Trump’s tweets would mention jobs, China and immigration, which – if the diversion were successful – would then be followed by less coverage of the Mueller investigation by NYT and ABC the following day. The logic is illustrated in the graphic below.

Our analyses provided strong evidence that Trump’s tweets were distracting the media. For example, we found that each ABC headline relating to the Mueller investigation was associated with 0.2 additional mentions of one of the keywords in Trump’s tweets. In turn, each additional mention of one of the keywords in a Trump tweet was associated with 0.4 fewer occurrences of the Mueller investigation than expected in the following day’s NYT.

To explore the robustness of these results, we also conducted an expanded analysis that considered the president’s entire Twitter vocabulary as a potential source of diversion. This analysis corroborated our findings: “jobs” and “China” were still Trump’s top picks, but “tax”, “crime” and “North Korea” also featured prominently as diversionary topics.

We also conducted a battery of checks to rule out alternative explanations and strengthen our claims of causal relationships between: a) the Mueller/Russia coverage and Trump’s diversionary tweets, and b) his tweets and the subsequent decrease in Mueller/Russia coverage.

To illustrate, when we considered “placebo topics”, such as Brexit, no diversion was observed. These placebo topics presented no political threat to Trump and were selected to span a variety of unrelated domains, including football and gardening. In other words, only media reports on Mueller/Russia – but not reports on placebo topics – resulted in an increase in diversionary Trump tweets.

It may well be the case that the media is not aware of the influence that Trump’s tweeting has on them. The NYT, for example, has explicitly warned about the impact of Trump’s presidency on journalistic standards. But the fact that suppression occurs (when important stories are not followed up after Trump’s diversionary tweets) nonetheless implies that important editorial decisions may be influenced by factors relating to Trump’s tweets. This may well happen without the editors’ intention – or indeed against their stated policies.

Strategic diversion is not a new political tool. It was the topic of the 1997 film “Wag the Dog”, which saw commentators draw parallels to then President Bill Clinton’s handling of the Monica Lewinsky scandal. The former adviser to Boris Johnson, Lynton Crosby, famously used a dead cat analogy to describe the strategy. However, social media has allowed political leaders more direct and immediate access to their constituents and the media. Our analysis shows that they can use this pathway effectively to divert.

Read more: Fox News, Donald Trump's cheerleaders and the journalists who challenged his narrative

Even though Trump failed to be re-elected, he continues to use Twitter prolifically (despite some of his tweets being taken down for being misleading). As the reach of social media platforms continues to grow, other present and future leaders may engage in similar types of behaviour in an attempt to steer the media narrative.

Perhaps our paper can serve as a reminder to the media that its role in a democracy is to highlight the topics most important to their audiences and to serve the public interest. This sometimes means ignoring the red herrings laid out on Twitter. Thankfully, some journalists, scholars and commentators have already worked this out.