As Venezuela’s democracy careens ever faster towards authoritarianism, its citizens are rising up to resist what’s happening. The rest of the world sees it mainly through images of violent protests and crackdowns – but resistance takes many forms.

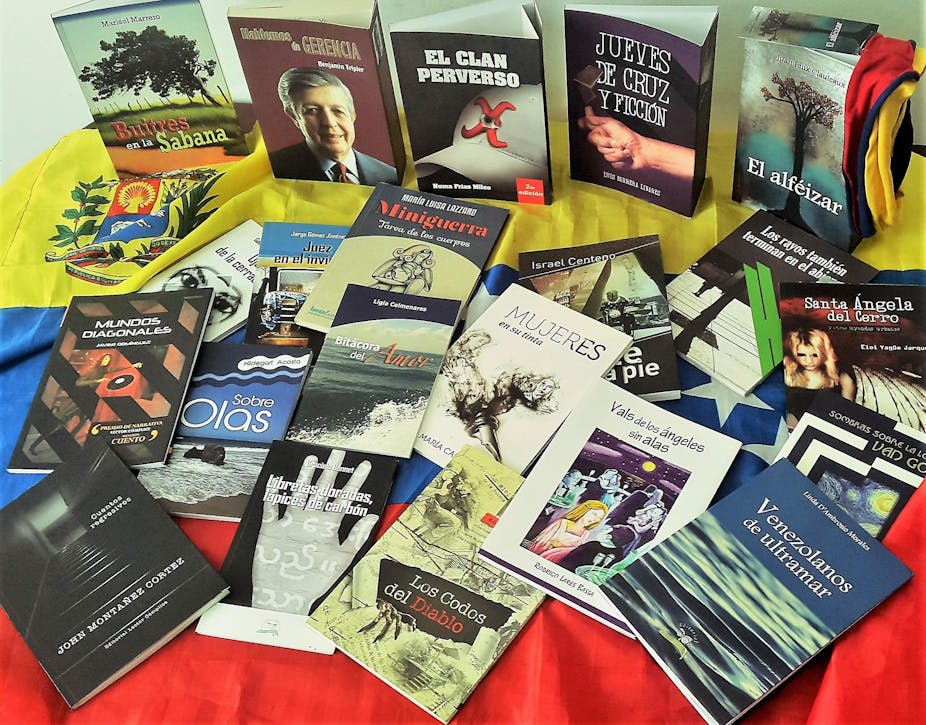

On July 27, days before a vote for a constituent assembly which critics fear will lead the country into a dictatorship, Les Quintero, editor of independent publisher Lector Cómplice, posted a picture of recent books from the publishing house with the caption “nuestros autores cómplices son resistencia” – “our writers are resistance”.

In recent years, Venezuela’s independent publishers and booksellers have blossomed, providing stories that attempt to make sense of the current situation. At the same time, reading brings communities together both in person and online; as writer Roberto Echeto argues, “Venezuelans have discovered through the force of suffering what books are for”.

As part of my research, I’ve interviewed a range of Venezuelan authors. They agree that Venezuelans are now reading more of their own literature, not because of the reading programmes put in place by the government, but because books – especially creative non-fiction (crónicas) and historical novels – have become a way for readers to process their political, economic and social realities, as this recent reading list shows.

Novelist Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles recently called for writers to tell stories of “artificial democracies”, in the tradition of fictional dictatorships; novels such as Federico Vegas’s Falke, which identifies traces of Venezuela’s present in its dictatorial past, have become bestsellers.

Meanwhile, many crónicas and short stories focus on everyday lives, and the critical problems that Venezuelans have to live with. The 2016 Latinobarómetro survey found they’re the most likely people in Latin America to be victims of crime (48%) and nearly twice as likely as any others to report food shortages (72%). Perhaps unsurprisingly, an estimated 1.5m Venezuelans now live outside the country.

While my fellow editors and I were putting together Crude Words, an anthology of contemporary Venezuelan writing in translation, we were struck by how many of the hundreds of submissions we received were coloured by violence, fear, shortages and emigration. But as Alberto Barrera Tyszka wrote in the foreword to the collection, Venezuela is “a country – above and beyond any economic or social indicator, beyond any Utopia too – that continues writing itself from the perspectives of fear, of death, but also from that of sex, or from that of love”.

Rise of the independents

It is an act of resistance to show people carrying on, refusing to lose their humanity. Gisela Kozak Rovero, editor of a new collection of crónicas entitled Siete Sellos, stresses the importance of not forgetting what Venezuela has given to the world in terms of art, culture and innovation, nor the tastes, sounds, and people which make up the country.

Lector Cómplice is just one of 23 independent publishers offering an alternative to the state-run publishing system, which is highly subsidised through oil revenue. Others include Fundación para la Cultura Urbana (Foundation for Urban Culture), Puntocero, Madera Fina and Libros de Fuego (Books of Fire), whose name remembers all the books through history which have been burned or otherwise censored. These independent publishing houses survive on the initiative and determination of the individuals who run them and support from loyal readers – but it’s far from easy.

Venezuelan newspaper El Universal reported in 2013 that unlike state publisher Monte Ávila, independent publishers face a huge rise in costs and paper shortages, limiting what they can print. In 2010, the state tried to shut down Cultura Urbana, locking the offices and seizing all the books. This led to public outcry, with 905 people signing a petition to save the foundation. This reaction was not only due to respect for the foundation itself, but a sign of growing frustration about the government’s power over culture.

The survival of these publishers has coincided with the development of social media and literary websites such as Ficción Breve, where a sense of community is based on a shared appreciation of literature. On Prodavinci, extracts from novels and short stories sit side by side with opinion pieces about contemporary politics by writers, encouraging debate about how art can help in the current situation.

Independent bookshops such as Caracas’s Lugar Común and El Buscón and Mérida’s Ballena Blanca are helping to turn reading into a social practice, online and off. They frequently host Skype calls with authors abroad, keeping the community together virtually; Lugar Común’s Rebeca Pérez Gerónimo called her shop “a meeting place, a mini cultural centre”. Perhaps the best example of social reading is the annual festival in Chacao, Caracas, with its slogan “LeerJuntos” (read together).

Last year, I witnessed how the festival provided a safe space for people to gather in the city centre, at a time when it was unusual to see people on the streets. And even though this year’s festival was postponed due to the increasingly violent protests, reading together is still a vital way to resist.