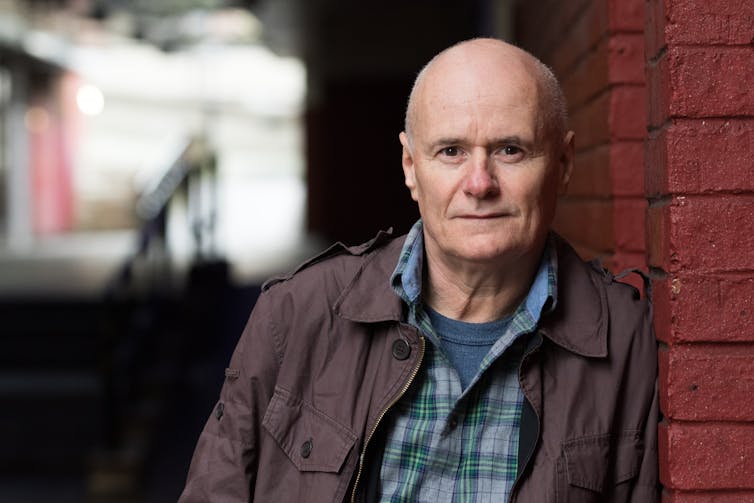

Ken Loach’s latest film was screened at the prestigious Cannes film festival in May, where it was awarded the top competition prize, the Palm D’Or. No surprises there – I, Daniel Blake cements Loach’s continued importance not only as a film director but also as a shrewd social commentator and committed political activist. It is a film that is both gripping and perfectly politically timed, telling as it does the story of a man who through no fault of his own finds himself caught in a harsh world of uncaring bureaucrats, food banks and benefits cuts.

Ken Loach began his directing career at the BBC in the 1960s. He soon made his name making socially engaged dramas such as Cathy Come Home, which through its heartbreaking story of a family’s struggle to keep their heads above water brought the issue of homelessness to the public’s attention when it was broadcast to great acclaim in 1966. But both Loach and Tony Garnett, his producer at the time, have since reflected that the film lacked a real political analysis of how people ended up homeless and on the street, and more importantly who was to blame and who could provide a solution. Speaking more recently, Garnett said: “Cathy let everybody off the hook … It didn’t put the boot in where it should have done.”

The finger of blame

Fifty years on, Loach is still looking for who to point the finger of blame at; where to stick the proverbial boot in. With I, Daniel Blake, he hones in on the people behind changes to the benefits system , which have seen those, such as disabled people and young families, least able to help themselves in the cross hairs as easy targets for cuts.

He also takes a well-aimed swipe at those heartless individuals working within the system who simply “carry out orders”. There is a memorable scene in the film where a benefits office worker is scolded by her superior merely for taking the time to try and help the slightly bemused Daniel. The implication is that such thoughtful assistance will not deliver the right productivity results and therefore must be eliminated.

Typical of Loach, I, Daniel Blake is a film that engages with the harsh social conditions within many parts of the UK in the second decade of the 21st century. Loach and his producer Rebecca O’Brien, alongside another long time collaborator, writer Paul Laverty, have forged a work that is driven by anger and dismay at the fact that such a state of affairs exists in a wealthy country like the UK.

The film focuses on Daniel Blake, played by comedian Dave Johns, a man who has worked hard all his life but finds himself on the wrong side of benefits cuts following a heart attack. As he tries to work his way through the labyrinth of the unfamiliar welfare system, he befriends Katie (Hayley Squires) a young mother forced to uproot her young family from London due to a lack of affordable council housing.

The choice of a heart attack as the reason for Daniel being unable to work is a crucial one, emphasising as it does his “every person” status. Such a condition is all too common in today’s society and something most people can easily relate to. Here Loach and his collaborators make Daniel stand for many of us – one small medical emergency away from the breadline. The logic is, if we could all be Daniel Blake then we should all be angry at the system that, as represented on screen, lets him down.

Hope in the future

For me, one of the most striking and under-commented upon aspects of the film is its representation of young people. Early in the film, we see Daniel berate his young black neighbour for continually leaving smelly rubbish on the walkway between their flats. This implies that the film might collaborate in the common image of lazy, workshy working class youths, continually off their faces on drink and drugs, that is so often peddled across the mainstream media. But as the film progresses, showing young people as helpful and caring, their petty scams are revealed as simply a way to make ends meet in an austerity Britain that does not provide anything for them.

So, when Daniel struggles with the computers in the public library, it is a pair of young, helpful characters who both do their best to assist him. Young people, from these characters to Katie and her children, offer an optimism for the future in a film that paints an otherwise bleak picture of the UK. They may struggle to make ends meet, but they care about their fellow human beings, and most of all are willing to chip in to help.

It is in these small moments that Loach shows us, as he has done from The Big Flame (1969) to Land and Freedom (1995), that young people are the future and provide hope and optimism amongst the despair. None more so than Katie’s young daughter, Daisy (Briana Shann), who, when Daniel has not been round to see them for a while, simply knocks on the door and quietly asks how she can help him after all he has done for them. Like many of Loach’s previous works, it is in its characters that I, Daniel Blake is a film of hope and belief.

At a preview screening in Manchester, Loach argued that even though I, Daniel Blake creates a picture of a Britain that marginalises and impoverishes its weakest, he still has hope in the will of the people to change things in the face of the sort of brutality shown in his film. At the centre of that belief is a continued commitment to the idea that a socialist movement can organise against austerity and provide an optimistic future for those represented by the characters of Daniel, Katie and her children.

The audience responded by giving the director a standing ovation. His final words were that with a growing socialist movement, perhaps best reflected in the large numbers of people joining the Corbyn-led Labour Party, this was the first time in his 80 years that he had felt the door to real political change was open. The job now, then, is to kick it in.