Customer service in banking is hard. Take a look at any bank’s Facebook or Twitter account and complaints heavily outnumber compliments. Westpac, one of Australia’s largest banks is a good example. Every day, Westpac faces a barrage of complaints on Facebook and Twitter.

Westpac is trying to address the problem by changing incentives for branch staff to be based on customer feedback. The trouble with this is that it relies on customers taking the time to go online and make a complaint or send a compliment. Most will simply just complain to their friends and family or just avoid using branches as much as possible.

The inherent problem with these types of jobs is that they require staff to be aware of a great deal of information about the bank’s regulations and processes and to be able to fit that to each customer’s unique circumstances and requirements. Add to that each individual’s motivation to actually be customer focused rather than optimising their own, or the banks’ needs, and you get the hit-or-miss quality of service that you will encounter at any given branch. Judging by feedback on social media (and personal experience), the banks are falling short of keeping all staff properly trained and consistently delivering customers with a great experience.

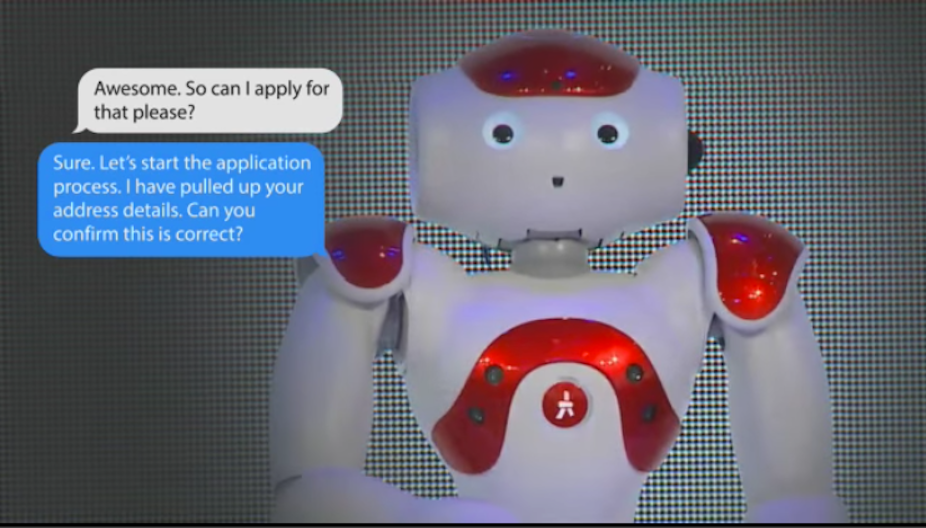

This is where a service like IBM’s Watson could make a radical difference in the quality and accuracy of customer service. Watson is an implementation of what IBM calls cognitive computing. This is a collection of technologies that include speech, video and text recognition coupled with analytics, machine learning and other artificial intelligence techniques.

Watson can take all of a bank’s rules and regulations and data about customer’s requirements and behaviours and provide an intelligent interface for customers to get things done with the confidence that Watson understood what the customer wanted and also understood what the bank could provide to satisfy those requirements.

The ideal situation would be that bank tellers could be guided by a service like Watson with the ability to provide a human face to the interaction with a customer. However, for most customers, being able to carry out transactions online, or through an app, without having to go into a branch would be even better. IBM Watson could certainly drive that type of interaction, free of human involvement.

Not surprisingly however, banks worldwide are not investing in innovations like cognitive computing. Innovation is often lumped in the general IT budget and often forms a tiny part of that spend. By viewing it in the same category as buying computers or complying with regulatory requirements, the overall value and benefit is much harder to see.

In the US, Citigroup has been the most active bank to explore the use of Watson to improve customer interactions with the bank.

ANZ, one of the more innovative of Australia’s banks has been collaborating with IBM to use Watson to power a financial advice service.

The fact that other banks are not investing in this technology is another example of how the major banks, in Australia at least, are under little pressure to innovate or improve because there is so little real competition, combined with a business that makes large amounts of money irrespective of customers’ views. Where there is an effective cartel operating, changing behaviours relies on governments and their agencies. However, as in the case of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s investigation of banks withdrawing services to bitcoin companies over the past few years, the ACCC takes a literal view of collusion, even in the face of all banks operating in concert to achieve the same outcome. As long as they didn’t all block services at the same time, it seems that this was sufficient to show that the banks were not acting in collusion.

Some banks are responding to the need to innovate and to deal with the ongoing perception/reality of poor customer service. In the meantime however, customers faced with poor service can simply try the approach of going to another branch in the hope that someone different will be better. Larger city branches are usually better than smaller suburban or rural ones but getting great service may simply be a matter of luck.

Optimal selection of branches to increase the chance of good service would be an ideal research question to ask Watson.