Much of the creative work we value – whether it’s films, music, novels, or TV shows – requires a significant input of time and resources. The established method for raising the resources to fund such work is copyright – which gives creators an exclusive right to communicate their work to the public (with some small limitations). In its most familiar use, creators raise resources by selling copies of their work.

The spread of computer technology that makes copying very cheap and easy has led, however, to a lot of angst. Copyright owners complain that widespread infringement threatens their ability to fund new creative works. On the other hand, apologists for infringement insist that copyright owners have it too good already, that they use the quasi-monopoly created by copyright to enrich themselves at the expense of users.

Over my career as a researcher in copyright protection technology, one of the most common pieces of advice to copyright owners that I heard was to “get a new business model”.

But what might that business model be?

In this article, I’ll restrict myself to the music industry, which has one of the longest and loudest experiences with online copyright infringement. As we’ll see, online music retailers and individual musicians have trialed quite a few models over the years.

Subscription services and bundling

Legal scholar Terry Fisher and recording company executive Jim Griffin, among others, have proposed “flat-fee” models in which users pay a subscription in order to access a pool of music.

Griffin’s own venture, Choruss, shut down in 2010 – though subscription services such as Rhapsody have been operating for many years. Subscription services are also on the march in the video industry.

Choruss targeted the US college market by offering a blanket licence to access music from the college network. PlayLouder MSP (Media Service Provider) tried bundling music and internet access in the UK back in 2003 – but the last news I found from the company was back in 2010 and the company’s website no longer functions.

Nokia also tried bundling music and mobile phones under the name Comes with Music, but withdrew the system from most markets in 2011.

Advertising

Established radio and television broadcasters have supported themselves through advertising for decades.

Streaming services such as Pandora and Spotify bought ad-supported music to the internet, with additional features such as recommendations and playlists. Spotify got some listeners excited but many artists complain that Spotify and others like it only pay a pittance.

Viral models

Experimental systems PotatoSystem (in German) and Weed tried a “viral” model in which songs can be transmitted from user to user.

In some versions, sharers may receive a credit when a downstream user buys the song. Microsoft also tried a viral strategy called Squirt via its Zune player – but ceased manufacturing the device in 2011.

Donations

Radiohead famously offered its 2007 album In Rainbows in return for donations rather than a fixed price. The band never published the financial results of the experiment, but they haven’t returned to the strategy for later releases.

Nine Inch Nails even gave its albums away for free for a time, but it has also ceased this generous policy.

Some have pointed out that such generosity might be feasible for bands who have established large followings (and, presumably, bank accounts) through the major label system, but wonder how unknown bands could ever attract donations.

Some bands do allow fans to set a price through Bandcamp – though most ask for a minimum price.

Crowdfunding

Some musicians – most famously, Amanda Palmer – have recently turned to crowdfunding sites such as Kickstarter to fund the recording of albums. In return, backers receive a copy of the completed album or other rewards.

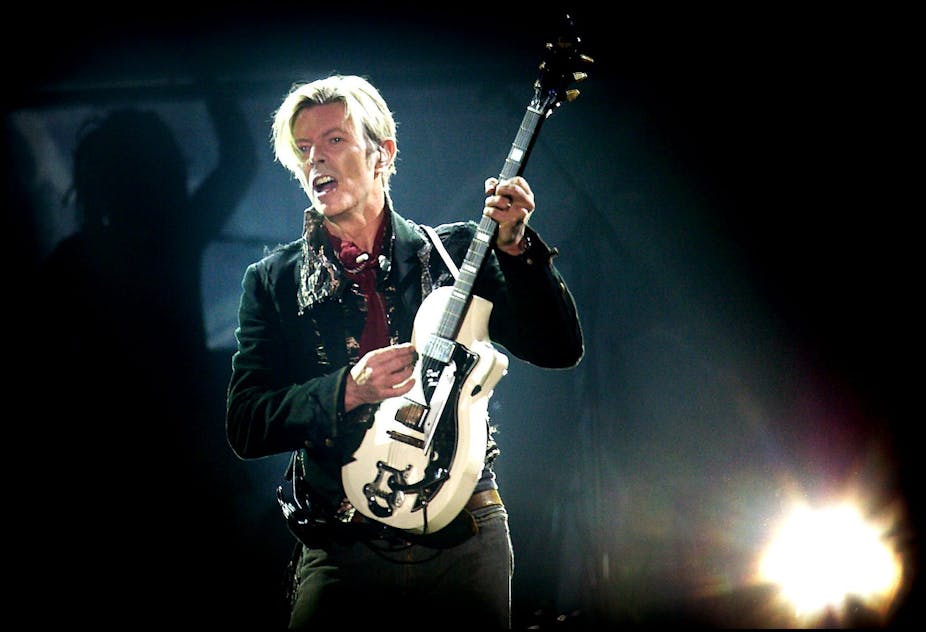

David Bowie actually tried something like this back in 1997, when he raised US$55 million by issuing “Bowie bonds” backed by future sales of his music, but other artists have been slow to follow.

What works?

For all of the above experimentation, iTunes remains the most popular retailer, using the old buy-a-copy model.

The subscription model, in the form of Rhapsody and Netflix, has shown similar longevity, but other models have struggled to attract the interest of major labels and/ or listeners, or have been abandoned by their creators. Others haven’t been around long enough to say.

Of course, factors other than the business model contribute to the success or failure of individual services. A great business model might fail due to pricing, the mix of music available, market conditions, the quality of the implementation, or other factors. All of this contributes to new business models being easier said than done.

What’s more, copyright plays a role in many alternative business models as well: without it, subscription services could not demand subscriptions, internet radio would not have to pay at all, artists could not extract payment from viral distribution – and Bowie bonds would be worthless.

Read other articles in our Creativity series here.