It’s not often that grammar makes the news, but there’s currently a good natured spat going on between Melvyn Bragg and John Humphrys. Bragg hosts a long running BBC Radio discussion show called In Our Time, which is a fairly high-brow discussion in which he invites academics to discuss the intellectual legacy of certain ideas.

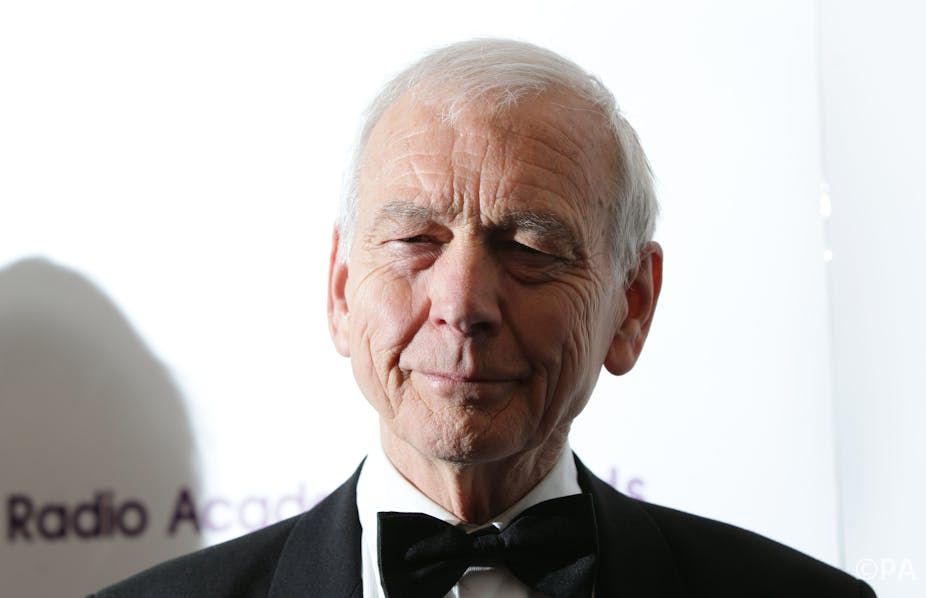

Humphrys has taken objection to the way Bragg tolerates the use of the present tense in order to describe past events – for example: “So, Darwin arrives on the Galapagos, starts to explore.” He calls this use the historic present, and thinks it “irritating and pretentious” – after all, the events happened a long time ago. Humphrys claims this is illogical, and it’s a case of academics lording their knowledge, leaving “ordinary Joes” such as himself feeling like “oiks”.

Bragg finally (reluctantly?) entered the fray on Wednesday in an article for The Times. “The historic present makes me wince,” he said. “But I’m sure it’s here to stay.”

Bragg, although still resistant to neologisms he doesn’t like, is taking the more sensible approach. The claims of illogicality fall flat when you consider how perfectly illogical the entire English tense system is if you choose to see it that way.

We use the present tense to talk about the past, as described above. We use the present tense to talk about the future (“Your plane leaves in an hour”, “I’m meeting my friend later”). We use the present perfect to describe events that happened much further in the past than other events, where we would use the past simple – “I have been to France twice in my life” compared to “My alarm clock didn’t go off this morning.” Frank Skinner once christened overuse of the present perfect the “footballer tense”: think of how often you hear descriptions like “so I’ve come on, I’ve seen the goal, I’ve gone for the ball, and I’ve scored”. We even use what is called the past participle to talk about things that have absolutely no connection to the past: “This bridge will be completed next year.”

And the illogicality of English goes beyond the tense system. I am taller than my father, but I still look up to him. I put out the cigarette, by putting it in the ashtray. The spelling of English is famously difficult, and the prefixes and suffixes are an area where even native speakers sometimes struggle.

Anyone who has taught English as a foreign or second language will have come across numerous examples. In fact, anyone who thinks about the absolute logic of what they are saying on a day-to-day basis can probably think of some.

But this is to miss the point. English grammar does have a logic, but one that is intertwined with aspect, voice, and metaphor. It also suffers from having been analysed through the lens of the classical languages for so long – which is why there is still a lingering whiff of raffish syntactical recklessness around the split infinitive or the sentence that ends with a preposition.

Michael Lewis, a highly influential writer on English Language Teaching in the 90s, has analysed the English verb system in a different way. He suggests that what we call the past tense would be better known as the distance tense.

In other words, it signals distance from the speaker. This could be chronological when describing the past. There is also the hypothetical distance, for example, “if I had more money” – which is an evolution of the subjunctive. There is also social distance, which is why a hotel receptionist might ask, “What was the name, sir?”. From this way of looking at things, the use of the present tense brings the events being described closer to the listener, making the events more vivid and immediate. This surely is only to be admired in a radio show whose purpose is to bring academic debates closer to a wider audience.

Which brings into question Humphrys’s motivation in kicking up this spat. Perhaps he sees himself as a stalwart defender of the grammar of the language he grew up speaking. If this is the case, I would suggest that he looks at some history – those who resist language change quickly become anachronisms, vainly defending against the tide of linguistic evolution. Or perhaps he has a personal gripe with Bragg, and he wants to air this in public. It’s possible, I suppose, but unlikely.

I think it much more probable that he’s realised that language use is for many people a button that can easily be pressed. He can use this to get attention from the press, and himself some publicity. And in doing so, he can somehow posit himself as the noble guardian of all that is good in traditional usage, and by extension traditional values. Criticising the language of others is a way of asserting your identity in a subtle but fairly pernicious way.

So perhaps it’s just that the sales of his book have dropped off.