Recent street protests in Suriname haven’t made many international headlines. Only newspapers in neighbouring Guyana and in the Netherlands, the colonial metropole, have covered the marches in which thousands of people have taken to the streets in recent weeks to protest spiraling economic chaos.

Suriname, a small nation on South America’s northern coast with a population of half a million, doesn’t often garner global attention. But maybe right now it should.

The next Venezuela?

Suriname’s current upheaval pales in comparison to the massive protests in nearby Venezuela, with (fortunately) no major casualties reported so far.

Yet events in Venezuelan are on many minds in Suriname, for both political and economic reasons.

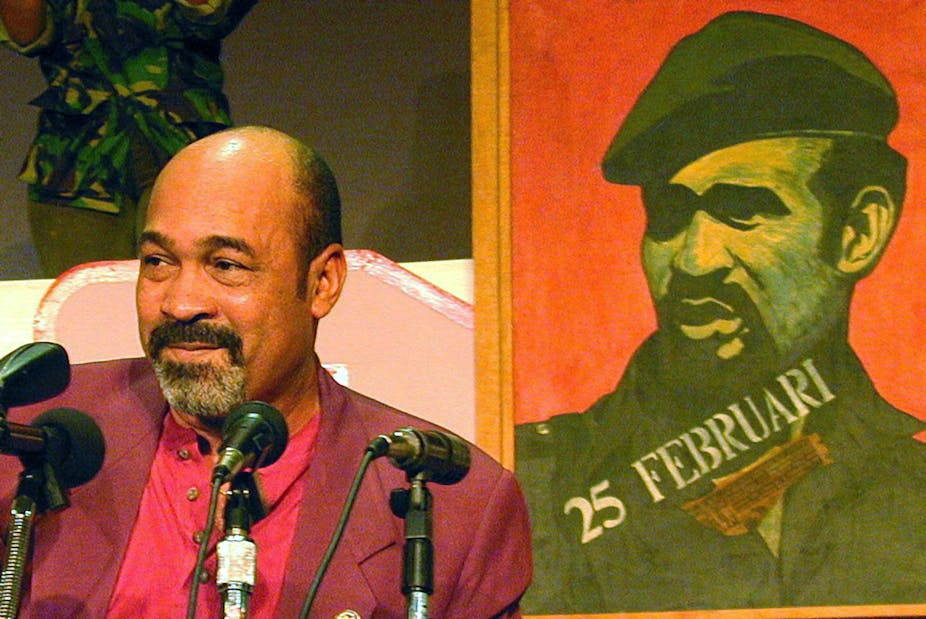

Surinamese President Desiré (Desi) Delano Bouterse is a great admirer of the late Hugo Chávez. Bouterse not only “adored” the man, as I have argued before, he also copied the Chavista hybrid political system, in which elections are held and opposition is allowed but weak institutions, clientelism, discretionary spending, and lack of transparency all advance the power of the executive – in this case, Bouterse’s.

Like Chávez, the opportunistic, charismatic, and controversial Bouterse also has a loyal following. He is especially popular among younger, lower-class Afro-Surinamese. Even a 1999 sentence in absentia to 11 years imprisonment for drug trafficking in a Dutch court did not hurt his popularity. In fact, it increased his street cred.

Sergeant Bouterse emerged on the national stage in February 1980, when he and 15 other non-commisioned military officers staged a coup against the democratically elected government. Their revolution – or “revo”, as it was locally called – soon became a nightmare as the dictatorship staged gross human rights violations, including the December 1982 massacre of 15 opposition leaders, economic collapse and social dislocation.

Bouterse did not disappear into the shadows with the return of democracy in 1987. He immediately founded a political party, the National Democratic Party (NDP), and in 2010 was elected president. In the last elections in 2015, his NDP gained an absolute majority in parliament, a first in Suriname’s history, and Bouterse was again re-elected.

So has this dictator really turned into a democrat? People who lived through the 1980s remember what Bouterse is capable of, and they fear a repeat of that period’s threats, violence and murders.

As days of protests turned into weeks, signs of the bad old days are beginning to show. Radio shows aired by NDP-run stations are threatening a Dutch-born young leader of the current protests, Maisha Neus, with deportation. Freedom of the press has been curtailed for several years, with critical media barred from official press conferences.

Boom and bust

The second Venezuelan link is that Suriname also suffers from the continuing decline in oil prices paired with populist spending policies. Natural resource exploitation has long been the basis of Suriname’s economy, forcing the country to undergo regular boom-and-bust cycles.

In the 20th century, bauxite mining generated foreign exchange revenues and financed a rapid increase in state expenditure. In the post-second world war period, respective governments have expanded the large state bureaucracy, employing tens of thousands of party supporters.

But Bouterse’s dictatorship (1980-1987) saw a sharp economic decline, with shortages and long shopping lines that many elderly Surinamese still remember vividly.

By the late 1990s, a downturn in international aluminium prices combined with the expansionary economic policies of the NDP administration of Jules Wijdenbosch had completely wiped out the recovery that had taken place earlier that decade. Inflation accelerated, undermining the value of Suriname’s currency.

In 1999, in the largest demonstration in the country’s history, 50,000 to 75,000 people (10% of the country’s population) protested the rising cost of living in the capital, Paramaribo.

Today’s protests are triggered by the same issues. Excessive spending and tumbling oil and gold prices have led to inflation at some 60% and halved the value of the Surinamese dollar. A spike in fuel prices has caused the initially small demonstrations to grow, and they are now attracting thousands of people, many of them in their 20s and 30s, including former Bouterse supporters.

The government is currently borrowing heavily to pay for hospitals, construction of infrastructure, food for the poor, and to repay outstanding debts. According to the Surinamese news magazine Parbode, since December 2015 Bouterse has taken out at least 17 loans from the International Monetary Fund, Eximbank China and other lenders.

Borrowing will only add to Suriname’s debt burden. According to the IMF, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to reach 68%. In February 2017, ratings agency Fitch lowered Suriname’s rating to B-minus.

Meanwhile, a coherent policy addressing the recession, depreciation, rise in inflation and government deficit is lacking.

Still, the ongoing protests are unlikely to lead to the resignation of their president. He claims to have a popular mandate, but that’s not the only reason why Bouterse won’t budge: human rights violations from the 1980s still haunt him.

Bouterse and his comrades are still being prosecuted for the 1982 execution of 15 opposition members. He has tried to put an end to this seemingly endless court case, several times in fact. But on May 11, despite the demands of the public prosecutor to stop the process because it allegedly endangered national security, the court decided to forge on.

The reaction of the Minister of Justice, Eugene van der San, was swift – “The government respects the judge’s decision” – then cryptic – “But there will be a moment when the executive power will be in charge again.”

Right now, Suriname’s economic and political future are uncertain, but one thing is clear: too few international eyes are watching the unfolding events.