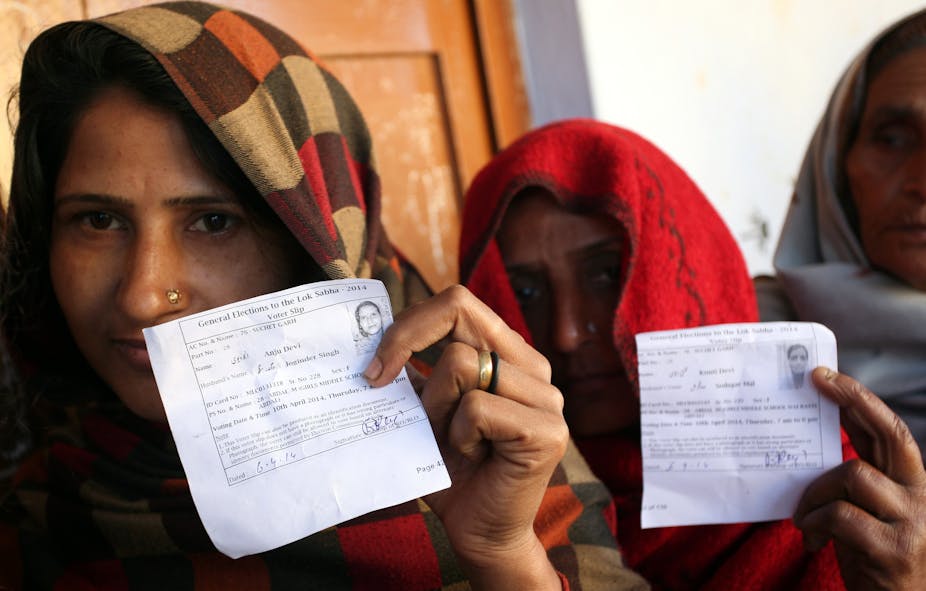

Over five weeks, 815m Indians will have the opportunity to choose a new government many hope will tackle inequality and corruption and lead the country to greater prosperity.

The choice is ostensibly between two men: Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Rahul Gandhi of the Congress Party. So how will India’s more than 200m women voters influence this election?

On March 8, 2014, a national “womanifesto” in India was launched by various activist groups asking candidates and parties to sign up to their six-point plan which called for action on education, justice and equal opportunity for women.

In particular, the womanifesto raised issues regarding female safety: calling for education programmes to end the culture of gender-based discrimination and violence, laws to end violence against women, to make all forms of rape criminal and to introduce comprehensive response protocols for the police in crimes against women.

Despite the vociferous local, national and international concerns and campaigns against sexual violence against women in India in the past 18 months, this issue is unlikely to affect the outcome of the general election.

Decades of struggle

The 2014 womanifesto includes a commitment to the Women’s Reservation Bill, which proposes that 33% of seats in the Lok Sabha and state assemblies are reserved for women. Some see this as a way of empowering women, championing their concerns and influencing government policy, but the yet-to-be-passed bill has been languishing in parliament since 2010 due to lack of consensus.

In the 1930s, when India was part of the British Empire and national women’s organisations were committed to fighting for full adult suffrage, all the main women’s groups: the Women’s Indian Association, the All-India Women’s Conference and National Council of Women in India, were vehemently opposed to reserved seats in parliament, arguing for a “fair field and no favour”.

Numerous petitions were sent to the imperial government opposing any quotas or special seats, arguing that once full adult suffrage was introduced women would naturally obtain positions of power.

Since 1950 when full universal adult suffrage was introduced, Indian men and women have elected a female prime minister and numerous female state ministers. Political participation for women in India has come a long way from the elite background of women who had been involved in politics in the 1930s, who were mostly connected to the imperial state through their families and wealth.

Still under-represented

However, the Women’s Reservation Bill is recognition of the continuing issue of female representation in Indian politics. At the moment, out of 28 states, only three: Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal have female chief ministers. Although in the end it may well be the chief minister of West Bengal, Mamata Banerjee, leader of the Trinamool Congress Party, who will decide who becomes the next prime minister as she decides what form of coalition to join.

The Woman’s Reservation Bill has faced vociferous opposition from members of other minority groups who worry that their own reservations and quotas will be affected and raises concerns whether a new reservation mandate will limit or increase state corruption. As things go, these issues for women will not be solved in this election.

While all political parties, including Narendra Modi’s BJP, have relied on female politicians, Bollywood stars and other female figures to endorse their party to appeal to women voters on the campaign trail, how are they addressing women’s issues in their manifestos, rather than through the cult of personality?

Arvind Kejriwal’s anti-corruption Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) supports much of the womanifesto while Congress includes passing the Women’s Reservation Bill in its manifesto. On the other hand, her recent statement that the rise in rape cases is due to increased interaction between the sexes suggests that Mamata Banerjee may be less than effective as a campaigner to prevent violence against women – and yet it is likely that her party will gain seats. The BJP as yet appear to have no manifesto.

That is not to say that the parties aren’t discussing women issues, or that there aren’t capable female candidates as well, but the issues highlighted in the womanifesto seem unlikely to affect the outcome. The key issues are about economic growth and tackling economic inequality for all social groups (not just women), including issues of welfare and investment and particularly inflation which is affecting all Indians.

Indians are concerned about allegations of bribery, and about ensuring they have a strong government. These concerns about corruption within all levels of state structures, including government, the police and law, encompass those that have manifested themselves again and again in response to noted rape cases, but go beyond women’s protection or discrimination.

The battle is being fought over the economy, jobs, education and corruption. Women are affected by all these issues. They also have other gender-specific concerns but a 33% reservation won’t be enough to help them as is evident by the lack of primacy women’s issues have taken in the election campaigns. Women will have to ensure that they are not merely token representatives of their sex but can actively challenge the priorities of the new, inevitably male-dominated, government after May 2014.