The world’s largest democratic election is set to take place in India. Voting will take place in seven phases from April 11 to May 19, and the result will be announced May 23.

An extraordinary 900 million people are eligible to vote, 130 million for the first time. Not only is it the “largest democratic exercise” in history, it is among world’s most expensive. In 2014, the Lok Sabha (lower house) elections cost the Election Commission of India half a billion US dollars.

Several key issues are emerging in this election that will prove decisive in voter decision-making behaviour. Unsurprisingly, economic development is front and centre. Despite having one of the world’s highest economic growth rates, growth slowed to 6.4% in the final quarter of 2018, down from a peak of 8.2% in mid-2018.

Unemployment rates are at their highest since the 1970s, as the economy struggles to create jobs for rural migrants moving to cities and a large youth cohort now entering the labour market. Unemployment and inflation, which directly affect household incomes, are widely seen as the biggest concerns for Indians in the lead up to the election.

Read more: India's WhatsApp election: political parties risk undermining democracy with technology

The spread of “fake news” and misinformation is also an important electoral complication. WhatsApp in India is tackling the spread of misinformation through a verification centre called Checkpoint. Indian users of the Facebook owned social networking service, of which there is 200 million, can send pictures, messages, and videos to be fact-checked.

This comes as Facebook removed hundreds of pages that shared misleading content about India and Pakistan following a suicide bombing in Kashmir. How to deal with these increasing tensions between India and Pakistan are a key feature of the political campaign.

How India’s electoral system works

India has a Westminster system of government, a legacy of the British Raj. In the Lok Sabha (lower house) there are 543 seats up for grabs. An additional two seats for the Anglo-Indian community are nominated by the president. These 545 seats will form the 17th Lok Sabha. The Prime Minister is selected from the members of the largest party or coalition.

There is no direct election for the Rajya Sabha (upper house). Rather, the current 233 Rajya Sabha members are elected by the Legislative Assembly in each of the states and the two union territories, with an additional 12 members nominated by the president. The Rajya Sabha may have up to 250 members, but it doesn’t reach this quota at present.

Read more: Kashmir: India and Pakistan's escalating conflict will benefit Narendra Modi ahead of elections

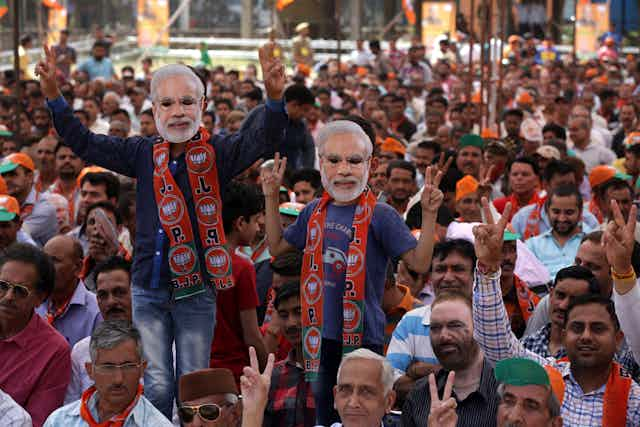

Narendra Modi versus Rahul Gandhi

There are two distinct personalities leading the major parties in this election. Both have taken advantage of the Representation of the People Act 1951 during their career, which allows candidates to contest an election from two seats – what the Wall Street Journal calls the “political equivalent of spread betting”.

Current Prime Minister Narendra Modi leads the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) – a Hindu nationalist party. Modi won both of the seats he nominated for in the 2014 elections, Vadodara in his home state of Gujarat, and Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh. He chose the seat of Varanasi and will recontest this seat in 2019. It is unknown whether he will contest a second seat, but there is speculation he might in the south of the country.

Leader of the opposition, Rahul Gandhi, leads the secular Indian National Congress (Congress). Gandhi has already declared that he will contest two seats in 2019, Amethi in Uttar Pradesh, as well as Wayanad in the southern state of Kerala.

Gandhi is latest generation of Nehru-Gandhi political dynasty, which has played a decisive role in Indian politics since independence in 1947. In keeping with family tradition, Gandhi recently appointed his sister Priyanka Gandhi as the All India Congress Committee secretary responsible for Uttar Pradesh. The All India Congress Committee is responsible for the Congress’ decision making.

Uttar Pradesh is the primary battleground

It’s no coincidence that both Modi and Gandhi will contest seats in Uttar Pradesh. Commentators often describe Uttar Pradesh as “the battleground state” of Indian elections. With a population size of roughly 230 million people, Uttar Pradesh sends more members to the Lok Sabha than any other state; it holds 80 seats, followed by Maharashtra (48), West Bengal (42) and Bihar (40).

The BJP won the 2014 election with an absolute majority in the Lok Sabha. The only time a party won by a larger majority was in 1984 following Indira Gandhi’s assassination, when Rajiv Gandhi led the Congress to win 78% of seats. But an absolute majority is more of an anomaly than the norm in recent Indian electoral history.

Read more: India: government continues to suppress citizens' right to information ahead of election

This means that in 2019, both the major parties are courting and negotiating with minor parties. Reports on the status of party alliances have the BJP performing strongly with the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), while Congress is struggling to build their opposition coalition.

It’s hard to predict whether Modi or Gandhi will emerge victorious in the election. Opinion polls are presently split. Modi and the BJP benefit from the advantages of incumbency, but recent deterioration in economic performance poses an opportunity for opposition parties.

Although it’s shaping up more like elections of the past, where the result will depend on negotiating party alliances, the 2019 Lok Sabha elections will still go down in history as the world’s biggest election.